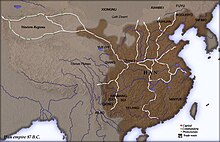

Han campaigns against Minyue

[1] During the concluding months of 111 BC, after the unsuccessful uprising led by Zou Yushan in thwarting General Yang Pu's conspiratorial intentions to undermine him, the aspiration for autonomous rule in Dongyue gradually waned.

[1][2][3] The Qin dynasty's initiative military incursions into what is now Southern China engendered an era of periodic expansion that continued under the Han.

The local rulers of the Minyue region had also sided with Liu Bang's Han instead of Xiang Yu's Chu during the Chu–Han Contention, a civil war that ensued during the collapse of the Qin.

[5][6] Minyue was created by carving out the former Qin province of Minzhong, with Dongye as the capital, into a new kingdom ruled by Zou Wuzhu.

A decade later, Zou Yao was granted control over Donghai, popularly referred to as Eastern Ou after the name of the kingdom's capital.

[5][6] While Minyue invasion of its neighbors appears to be a "spontaneous whim of a foolhardy and greedy king Zou Ying" in the Han dynasty history books,[7] given the geopolitical circumstances, Brindley (2015) wrote that "We should therefore consider Minyue aggression in the 130s in terms of a series of pre-emptive, southerly strikes intended to stave off Han encroachment and potential takeover.

In accordance with Chinese political philosophy, the ruler or Son of Heaven held a mandate that obligated the emperor to help smaller countries in need.

"[10][8] A Han naval force led by Zhuang Zhu departed from Shaoxing in northern Zhejiang towards Minyue.

Minyue was controlled by the Han through a proxy ruler, while Dongyue was independently ruled by Zou Yushan, the brother who deposed the former king during the invasion.

[1] Zou Chou was selected to fill the role of Han proxy ruler because he was the only member of the Minyue royal family who refused to take part in the war against Nanyue.

[8] The army crushed the rebellion and captured Dongyue in the last months of 111 BC, placing the former Minyue territory under Han rule.

[18] Political upheaval in the north, such as Wang Mang's usurpation, had sent waves of Northern Han migrants to resettle in the south.

This expansion of the Han dynasty's geopolitical sphere of influence invariably extended to the nearby Southeast Asian kingdoms, where foreign contact led to the diffusive percolation of Han Chinese culture, trade, and political diplomacy with the empire having broadened its overseas trade relations with the various Southeast Asian polities around the Indian Ocean.

The dynasty's conquest of Minyue and Nanyue spoke of its geopolitical influence, predominance, and prominence as the empire itself was exemplified by its military might, advanced technology, economic prosperity, and rich culture coupled with its immense topographical size and vast territorial reach that geographically loomed along the Southeast Asian polities.

Maritime trade and the Silk Road also linked Han China with Ancient Rome, India, and the Near East.