Chinese characters

The first attested characters are oracle bone inscriptions made during the 13th century BCE in what is now Anyang, Henan, as part of divinations conducted by the Shang dynasty royal house.

Clerical script, which had matured by the early Han dynasty (202 BCE – 220 CE), abstracted the forms of characters—obscuring their pictographic origins in favour of making them easier to write.

Historically, methods of writing characters have included inscribing stone, bone, or bronze; brushing ink onto silk, bamboo, or paper; and printing with woodblocks or moveable type.

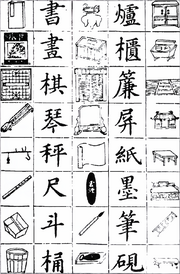

Due to this process of abstraction, as well as to make characters easier to write, pictographs gradually became more simplified and regularized—often to the extent that the original objects represented are no longer obvious.

[11] Despite their origins in picture-writing, Chinese characters are no longer ideographs capable of representing ideas directly; their comprehension relies on the reader's knowledge of the particular language being written.

[12] The areas where Chinese characters were historically used—sometimes collectively termed the Sinosphere—have a long tradition of lexicography attempting to explain and refine their use; for most of history, analysis revolved around a model first popularized in the 2nd-century Shuowen Jiezi dictionary.

Examples include 上 ('up') and 下 ('down')—these characters were originally written as dots placed above and below a line, and later evolved into their present forms with less potential for graphical ambiguity in context.

[29] For example, the Shuowen Jiezi describes 信 ('trust') as an ideographic compound of 人 ('man') and 言 ('speech'), but modern analyses instead identify it as a phono-semantic compound—though with disagreement as to which component is phonetic.

[30] Peter A. Boodberg and William G. Boltz go so far as to deny that any compound ideographs were devised in antiquity, maintaining that secondary readings that are now lost are responsible for the apparent absence of phonetic indicators,[31] but their arguments have been rejected by other scholars.

Some loangraphs (假借; jiǎjiè; 'borrowing') are introduced to represent words previously lacking a written form—this is often the case with abstract grammatical particles such as 之 and 其.

Later authors iterated upon Xu's analysis, developing a categorization scheme known as the 'six writings' (六书; 六書; liùshū), which identifies every character with one of six categories that had previously been mentioned in the Shuowen Jiezi.

[44] Xu based most of his analysis on examples of Qin seal script that were written down several centuries before his time—these were usually the oldest specimens available to him, though he stated he was aware of the existence of even older forms.

Cangjie is said to have invented symbols called 字 (zì) due to his frustration with the limitations of knotting, taking inspiration from his study of the tracks of animals, landscapes, and the stars in the sky.

On the day that these first characters were created, grain rained down from the sky; that night, the people heard the wailing of ghosts and demons, lamenting that humans could no longer be cheated.

By 1928, the source of the bones had been traced to a village near Anyang in Henan—discovered to be the site of Yin, the final Shang capital—which was excavated by a team led by Li Ji from the Academia Sinica between 1928 and 1937.

Although written Chinese is first attested in official divinations, it is widely believed that writing was also used for other purposes during the Shang, but that the media used in other contexts—likely bamboo and wooden slips—were less durable than bronzes or oracle bones, and have not been preserved.

Some attribute this name to the fact that the style was considered more orderly than a later form referred to as 今草 (jīncǎo; 'modern cursive'), which had first emerged during the Jin and was influenced by semi-cursive and regular script.

[81] Its innovations have traditionally been credited to the calligrapher Zhong Yao, who lived in the state of Cao Wei (extant 220–266); he is often called the "father of regular script".

Prior to this, the context of a passage was considered adequate to guide readers; this was enabled by characters being easier to read than alphabets when written without spaces or punctuation due to their more discretized shapes.

For example, 行 may represent either 'road' (xíng) or the extended sense of 'row' (háng): these morphemes are ultimately cognates that diverged in pronunciation but remained written with the same character.

During the Nara period (710–794), readers and writers of kanbun—the Japanese term for Literary Chinese writing—began utilizing a system of reading techniques and annotations called kundoku.

Starting in the 9th century, specific man'yōgana were graphically simplified to create two distinct syllabaries called hiragana and katakana, which slowly replaced the earlier convention.

[147] While the hangul alphabet was invented by the Joseon king Sejong in 1443, it was not adopted by the Korean literati and was relegated to use in glosses for Literary Chinese texts until the late 19th century.

[151] Following the end of the Empire of Japan's occupation of Korea in 1945, the total replacement of hanja with hangul was advocated throughout the country as part of a broader "purification movement" of the national language and culture.

[170] The memorization of thousands of different characters is required to achieve literacy in languages written with them, in contrast to the relatively small inventory of graphemes used in phonetic writing.

[182] While the level of memorization required for character literacy is significant, identification of the phonetic and semantic components in compounds—which constitute the vast majority of characters—also plays a key role in reading comprehension.

[191] During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, an increasing number of intellectuals in China came to see both the Chinese writing system and the lack of a national spoken dialect as serious impediments to achieving the mass literacy and mutual intelligibility required for the country's successful modernization.

Alongside the corresponding spoken variety of Standard Chinese, this written vernacular was promoted by intellectuals and writers such as Lu Xun and Hu Shih.

In 1935, the Republican government published the first official list of simplified characters, comprising 324 forms collated by Peking University professor Qian Xuantong.

In 1958, Zhou Enlai announced the government's intent to focus on simplification, as opposed to replacing characters with Hanyu Pinyin, which had been introduced earlier that year.