Pope Gregory I

A Roman senator's son and himself the prefect of Rome at 30, Gregory lived in a monastery that he established on his family estate before becoming a papal ambassador and then pope.

Gregory regained papal authority in Spain and France and sent missionaries to England, including Augustine of Canterbury and Paulinus of York.

[6] His contributions to the development of the Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts, still in use in the Byzantine Rite, were so significant that he is generally recognized as its de facto author.

Like most young men of his position in Roman society, Gregory was well educated, learning grammar, rhetoric, the sciences, literature, and law; he excelled in all these fields.

He knew Latin authors, natural science, history, mathematics and music and had such a "fluency with imperial law" that he may have trained in it "as a preparation for a career in public life".

[23] Indeed, he became a government official, advancing quickly in rank to become, like his father, Prefect of Rome, the highest civil office in the city, when only thirty-three years old.

[14] The monks of the Monastery of St. Andrew, established by Gregory at the ancestral home on the Caelian, had a portrait of him made after his death, which John the Deacon also saw in the 9th century.

[24] In the modern era, Gregory is often depicted as a man at the border, poised between the Roman and Germanic worlds, between East and West, and above all, perhaps, between the ancient and medieval epochs.

However, after the eldest two, Trasilla and Emiliana, died after seeing a vision of their ancestor Pope Felix III, the youngest soon abandoned the religious life and married the steward of her estate.

Eventually, Pope Pelagius II ordained Gregory a deacon and solicited his help in trying to heal the schism of the Three Chapters in northern Italy.

[30] Gregory was part of the Roman delegation (both lay and clerical) that arrived in Constantinople in 578 to ask the emperor for military aid against the Lombards.

[31] It soon became obvious to Gregory that the Byzantine emperors were unlikely to send such a force, given their more immediate difficulties with the Persians in the East and the Avars and Slavs to the North.

[32] According to Ekonomou, "if Gregory's principal task was to plead Rome's cause before the emperor, there seems to have been little left for him to do once imperial policy toward Italy became evident.

Papal representatives who pressed their claims with excessive vigor could quickly become a nuisance and find themselves excluded from the imperial presence altogether".

[32] Gregory had already drawn an imperial rebuke for his lengthy canonical writings on the subject of the legitimacy of John III Scholasticus, who had occupied the Patriarchate of Constantinople for twelve years prior to the return of Eutychius (who had been driven out by Justinian).

[32] Ekonomou surmises that "while Gregory may have become spiritual father to a large and important segment of Constantinople's aristocracy, this relationship did not significantly advance the interests of Rome before the emperor".

[32] Although the writings of John the Deacon claim that Gregory "labored diligently for the relief of Italy", there is no evidence that his tenure accomplished much towards any of the objectives of Pelagius II.

[39] In texts of all genres, especially those produced in his first year as pope, Gregory bemoaned the burden of office and mourned the loss of the undisturbed life of prayer he had once enjoyed as a monk.

[40] When he became pope in 590, among his first acts was writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks.

The episcopacy in Gaul was drawn from the great territorial families, and identified with them: the parochial horizon of Gregory's contemporary, Gregory of Tours, may be considered typical; in Visigothic Spain the bishops had little contact with Rome; in Italy the territories which had de facto fallen under the administration of the papacy were beset by the violent Lombard dukes and the rivalry of the Byzantines in the Exarchate of Ravenna and in the south.

Pope Gregory had strong convictions on missions: "Almighty God places good men in authority that He may impart through them the gifts of His mercy to their subjects.

The preaching of non-heretical Christian faith and the elimination of all deviations from it was a key element in Gregory's worldview, and it constituted one of the major continuing policies of his pontificate.

A central papal administration, the notarii, under a chief, the primicerius notariorum, kept the ledgers and issued brevia patrimonii, or lists of property for which each rector was responsible.

Hearing of the death of an indigent in a back room he was depressed for days, entertaining for a time the conceit that he had failed in his duty and was a murderer.

John the Deacon wrote that Pope Gregory I made a general revision of the liturgy of the Pre-Tridentine Mass, "removing many things, changing a few, adding some".

Gregory added material to the Hanc Igitur of the Roman Canon and established the nine Kyries (a vestigial remnant of the litany which was originally at that place) at the beginning of Mass.

The earliest such attribution is in John the Deacon's 873 biography of Gregory, almost three centuries after the pope's death, and the chant that bears his name "is the result of the fusion of Roman and Frankish elements which took place in the Franco-German empire under Pepin, Charlemagne and their successors".

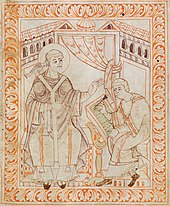

As, however, the pope remained silent for long periods at a time, the servant made a hole in the curtain and, looking through, beheld a dove seated upon Gregory's head with its beak between his lips.

[73] The miniature shows the scribe, Bebo of Seeon Abbey, presenting the manuscript to the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry II.

[96][97] The current General Roman Calendar, revised in 1969 as instructed by the Second Vatican Council,[98] celebrates Saint Gregory the Great on 3 September.