Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome

First, there is prodromal phase with flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, muscle, shortness of breath, as well as low platelet count.

Second, there is cardiopulmonary phase during which people experience elevated or irregular heart rate, cardiogenic shock, and pulmonary capillary leakage, which can lead to respiratory failure, low blood pressure, and buildup of fluid in the lungs and chest cavity.

In North America, Sin Nombre virus is the most common cause of HPS and is transmitted by the Eastern deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus).

In South America, Andes virus is the most common cause of HPS and is transmitted mainly by the long-tailed pygmy rice rat (Oligoryzomys longicaudatus).

Sin Nombre virus was found to be responsible for the outbreak, and since then numerous other hantaviruses that cause HPS have been identified throughout the Americas.

An open reading frame in the N gene on the S segment[11] of some hantaviruses also encodes the non-structural protein NS that inhibits interferon production in host cells.

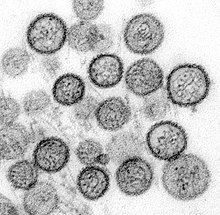

[10] Each surface spike is composed of a tetramer of Gn and Gc (four units each) that has four-fold rotational symmetry and extends about 10 nm out from the envelope.

It can also reportedly spread through human saliva, airborne droplets from coughing and sneezing, and to newborns through breast milk and the placenta.

[2] A 2021 systematic review, however, found these claims not to be supported by sufficient evidence and cited flawed methodology in research about Andes virus outbreaks.

[3] The expansion of agricultural land is associated with a decline in predator populations, which enables hantavirus host species to use farm monocultures as nesting and foraging sites.

[23] Seroprevalence, which shows past infection to hantavirus, is consistently higher in occupations and areas that have greater exposure to rodents.

[22] The main cause of illness is increased vascular permeability, decreased platelet count, and overreaction by the immune system.

[3][6] Infection begins with interaction of the viral glycoproteins Gn and Gc and β-integrin receptors on target cell membranes.

For the same reason, infection of the heart leads to interstitial fluid buildup that contributes to myocardial disfunction and cardiogenic shock.

In the spleen, infection of immune cells can cause over-activation of immature lymphocytes elsewhere and facilitate prolonged spread of the virus throughout the body.

This triggers production of interferons, immune cytokines, and chemokines and activation of signaling pathways to respond to viral infection.

[2] Ventilation of rooms before entering, using rubber gloves and disinfectants, and using respirators to avoid inhaling contaminated particles while cleaning up rodent-infested areas reduce the risk of hantavirus infections.

[2] Key laboratory findings include thrombocytopenia, leukocytosis, hemoconcentration, elevated serum creatinine levels, hematuria, and proteinuria.

[12] Both traditional and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests of blood, saliva, BAL fluids, and tissue samples can be used.

Treatment entails continual cardiac monitoring and respiratory support, including mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), and hemofiltration.

[30] Since high nAb titers are associated with favorable outcomes, fresh frozen plasma and sera from recovered individuals has been used to treat HPS and lower the case fatality rate.

[31][32] No specific antiviral drugs exist for hantavirus infection, but ribavarin and favipiravir have shown varying efficacy and safety.

[2] Prophylactic use of ribavirin and favipiravir in early infection or post-exposure show some efficacy, and both have shown some anti-hantavirus activity in vivo and in vitro.

Ribavirin is effective in the early treatment of HFRS with some limitations such as toxicity at high doses and the potential to cause hemolytic anemia.

In some instances, ribavirin may cause excess bilirubin in the blood (hyperbilirubinemia), abnormally slow heart beat (sinus bradycardia), and rashes.

Early production of neutralizing antibodies (nAbs) that target the surface glycoproteins is directly associated with increased likelihood of survival.

[34] Rodent species that carry hantaviruses inhabit a diverse range of habitats, including desert-like biomes, equatorial and tropical forests, swamps, savannas, fields, and salt marshes.

[19] The seroprevalence of hantaviruses in their host species has been observed to range from 5.9% to 38% in the Americas, and 3% to about 19% worldwide, depending on testing method and location.

An example of this was the 1993 Four Corners outbreak in the United States, which was immediately preceded by elevated rainfall from the 1992–1993 El Niño warming period.

Heavy rainfall is a risk factor for outbreaks in the following months,[7] but may negatively affect incidence by flooding rodent burrows and nests.