Harold F. Cherniss

"[1] According to Leonardo Tarán, Cherniss's "greatest contribution to scholarship is doubtless his two books on Aristotle, supplemented by The Riddle of the Early Academy ... his published works on Plato, Aristotle, and the Academy are among the very few publications that revolutionized the field... His significance was recognized all over the world not only by classicists and philosophers but by the learned societies of which he was a member and the various universities that awarded him honorary degrees.

The Russian government then adopted a systematic policy of excluding Jews from their economic and public roles, and this provoked a mass emigration of Jewish refugees from Russia to the United States and other countries.

[6] Later, during the Nazi occupation of Ukraine in the early 1940s more than a million Ukrainian Jews perished in the Holocaust, including tens of thousands in Vinnytsia.

[10] From 1927 to 1928, Cherniss studied with some of the leading classicists in Germany: in Göttingen with Hermann Fränkel and in Berlin with Werner Jaeger and Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff.

[12] Influenced by the brief cultural explosion in the Soviet Union, German literature, cinema, theater, jazz, art, and architecture were in the midst of a phase of great creativity.

I don't recall how he characterized the remarks, but Solmsen's description of the antidemocratic, anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic Prussian lens through which Wilamowitz viewed Weimar Germany would explain Cherniss's antipathy.

Lovejoy founded a "History of Ideas Club" at Johns Hopkins that included Cherniss, his friends Ludwig Edelstein and George Boas, and others: Like the Cambridge Apostles and the Metaphysical Society of the last century, the History of Ideas Club has set itself the threefold aim of intellectual stock-taking, the pursuit of new truth, and the "cross-fertilization" of the various academic departments and disciplines.

In September 1941, groups of Nazi commandos tasked with eliminating the Jewish population of Ukraine massacred some 50,000 people in Vinnytsia, where Cherniss's father was born.

[25] With the Berlin blockade of 1948–1949 and the Communist victory in China and first Soviet atomic bomb in 1949, America and Berkeley were soon caught up in Cold War tensions.

In the rising anxiety stoked by Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee, fears grew that communists were infiltrating American universities.

[27] As these tensions mounted, Cherniss accepted an offer from the Institute of Advanced Study and resigned from his post at Berkeley: "his tenure there was cut short by the controversy which arose from the California Legislature's demand that state employees swear loyalty oaths.

"[28] Back on the East Coast, Cherniss remained involved in what quickly became a national debate over Berkeley's loyalty oaths and academic Freedom.

[29] Recent immigrants among the faculty were particularly opposed: "persecuted by the Nazis and forced to leave Germany, they were rightly suspicious of the loyalty oath as a cold war demand for conformity or worse, inimical to the freedoms necessary at any institution of higher learning.

[31] The well-known German-Jewish medievalist Ernst Kantorowicz left Germany in 1939 after the Nazi government required civil servants to swear a loyalty oath to Hitler and became a professor at Berkeley.

[32] Cherniss's old colleague at Johns Hopkins, the classicist Ludwig Edelstein, had also moved to Berkeley after the war but refused to sign the loyalty oath and lost his job.

Anti-semitism was still widespread at this time in America even at universities like Princeton, but the Institute "employed scholars with absolutely no regard to religious persuasion or ethnicity.

Historians with access to the American and Russian evidence have since concluded Oppenheimer was never involved in espionage for the Soviet Union and did not betray the United States, though in the late 1930s he had been a supporter of the Communist Party.

This proved to be a miscalculation, because the delay gave members of the faculty time to organize an open letter in support of Oppenheimer… Strauss was forced to back off, and later that Autumn the trustees voted to keep Oppie as director.

"[42] Cherniss and other faculty members of the Institute for Advanced Study published an open letter affirming his loyalty on Thursday July 1, 1954, in both The New York Times and The Herald Tribune[43] and in the September Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists: We, who have known [Dr. Oppenheimer] as a colleague, as director of our own institute, and as a neighbor in a small and intimate community, had from the first complete confidence in his loyalty to the United States, his discretion in guarding its secrets, and his deep concern for its safety, strength, and welfare.

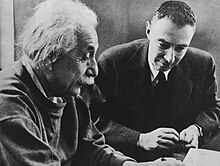

[44]The letter was signed by H. F. Cherniss, A. Einstein, Freeman Dyson, K. Gödel, E. Panofsky, J. von Neumann, Hermann Weyl, Chen Ning Yang, and others.

Cherniss's close friend and colleague, the art historian Erwin Panofsky, "considered the case a symbolic and sorry indictment of American society.

"[48]Cherniss discussed Renaissance philosophy with the physicist Wolfgang Pauli, a friend of the art historian Erwin Panofsky, at the Institute for Advanced Study.

"[52] In a memoir, Tarán said "this country has lost one of its greatest Hellenists and the history of ancient Greek philosophy one of its foremost scholars in the last two centuries.

"[66] Cherniss's landmark monograph transformed studies of Pre-Socratic philosophy by forcing scholars to re-evaluate their sources and raise the rigor of their arguments.

Cherniss demonstrated "in detail how much of the conceptual apparatus often attributed to Presocratic thinkers in fact represents Aristotle's own reformulation of their theories in terms of his own philosophy.

In each of these spheres there had been developed by the end of the fifth century doctrines so extremely paradoxical that there seemed to be no possibility of reconciling them with one another or any one of them with the observable facts of human experience.

The dialogues of Plato, I believe, will furnish evidence to show that he considered it necessary to find a single hypothesis which would at once solve the problems of these several spheres and also create a rationally unified cosmos by establishing the connection among the separate phases of experience.

In a famous paper that explicitly criticized Cherniss, the Oxford philosopher G. E. L. Owen argued that Plato's Parmenides marked a radical change in the Theory of Forms.

Owen, therefore, "sought to make his view plausible by proposing to remove the Timaeus from the late group and place it among the middle dialogues, after the Republic but before the Parmenides.

In the Fifties, however, the so-called Tübingen School, initiated by the German scholars Hans Krämer and Konrad Gaiser, resurrected esoteric interpretations of Plato.