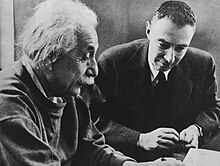

J. Robert Oppenheimer

In 1947, Oppenheimer was appointed director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and chairman of the General Advisory Committee of the new United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC).

He lobbied for international control of nuclear power and weapons in order to avert an arms race with the Soviet Union, and later opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb, partly on ethical grounds.

[7] His father was born in Hanau, when it was still part of the Hesse-Nassau province of the Kingdom of Prussia, and as a teenager made his way to the United States in 1888, without money, higher education, or even English.

He was admitted to the undergraduate honor society Phi Beta Kappa and was granted graduate standing in physics on the basis of independent study, allowing him to bypass basic courses in favor of advanced ones.

Oppenheimer made friends who went on to great success, including Werner Heisenberg, Pascual Jordan, Wolfgang Pauli, Paul Dirac, Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller.

[38] On returning to the United States, Oppenheimer accepted an associate professorship from the University of California, Berkeley, where Raymond Thayer Birge wanted him so badly that he expressed a willingness to share him with Caltech.

[112]In spite of this, observers such as physicists Luis Alvarez and Jeremy Bernstein have suggested that if Oppenheimer had lived long enough to see his predictions substantiated by experiment, he might have won a Nobel Prize for his work on gravitational collapse, concerning neutron stars and black holes.

The mix of European physicists and his own students—a group including Serber, Emil Konopinski, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, and Edward Teller—kept themselves busy by calculating what needed to be done, and in what order, to make the bomb.

[122][123] In June 1942, the U.S. Army established the Manhattan Engineer District to handle its part in the atom bomb project, beginning the process of transferring responsibility from the Office of Scientific Research and Development to the military.

"[152][153] According to a 1949 magazine profile, while witnessing the explosion Oppenheimer thought of verses from the Bhagavad Gita: "If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one ... Now I am become Death, the shatterer of worlds.

Like many scientists of his generation, Oppenheimer felt that security from atomic bombs could come only from a transnational organization such as the newly formed United Nations, which could institute a program to stifle a nuclear arms race.

He directed and encouraged the research of many well-known scientists, including Freeman Dyson, and the duo of Chen Ning Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee, who won a Nobel Prize for their discovery of parity non-conservation.

Under Oppenheimer's direction, physicists tackled the greatest outstanding problem of the pre-war years: infinite, divergent, and seemingly nonsensical expressions in the quantum electrodynamics of elementary particles.

[186] After the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) came into being in 1947 as a civilian agency in control of nuclear research and weapons issues, Oppenheimer was appointed as the chairman of its General Advisory Committee (GAC).

[193] He and the other GAC members were motivated partly by ethical concerns, feeling that such a weapon could only be strategically used, resulting in millions of deaths: "Its use therefore carries much further than the atomic bomb itself the policy of exterminating civilian populations.

[213] Oppenheimer was a late addition to the project in 1951 but wrote a key chapter of the report that challenged the doctrine of strategic bombardment and advocated smaller tactical nuclear weapons which would be more useful in a limited theater conflict against enemy forces.

[222] Strategic thermonuclear weapons delivered by long-range jet bombers would necessarily be under the control of the U.S. Air Force, whereas the Vista conclusions recommended an increased role for the U.S. Army and U.S. Navy as well.

[226] The panel then issued a final report in January 1953, which, influenced by many of Oppenheimer's deeply felt beliefs, presented a pessimistic vision of the future in which neither the United States nor the Soviet Union could establish effective nuclear superiority but both sides could inflict terrible damage on the other.

[237] In August 1943, Oppenheimer told Manhattan Project security agents that George Eltenton, whom he did not know, had solicited three men at Los Alamos for nuclear secrets on behalf of the Soviet Union.

[240] He testified that some of his students, including David Bohm, Giovanni Rossi Lomanitz, Philip Morrison, Bernard Peters, and Joseph Weinberg had been communists at the time they had worked with him at Berkeley.

[72][241] The triggering event for the security hearing happened on November 7, 1953,[242] when William Liscum Borden, who until earlier in the year had been the executive director of the United States Congress Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, sent Hoover a letter saying that "more probably than not J. Robert Oppenheimer is an agent of the Soviet Union.

"[243] Eisenhower never exactly believed the allegations in the letter but felt compelled to move forward with an investigation,[244] and on December 3, he ordered that a "blank wall" be placed between Oppenheimer and any government or military secrets.

[245] On December 21, 1953, Strauss told Oppenheimer that his security clearance had been suspended, pending resolution of a series of charges outlined in a letter, and discussed his resigning by way of requesting termination of his consulting contract with the AEC.

Significantly, after his public humiliation, he did not sign the major open protests against nuclear weapons of the 1950s, including the Russell–Einstein Manifesto of 1955, nor, though invited, did he attend the first Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs in 1957.

[290] In his speeches and public writings, Oppenheimer continually stressed the difficulty of managing the power of knowledge in a world in which the freedom of science to exchange ideas was more and more hobbled by political concerns.

Senator Bourke B. Hickenlooper formally protested Oppenheimer's selection just eight days after Kennedy was killed,[303] and several Republican members of the House AEC Committee boycotted the ceremony.

"[327] The question of scientists' responsibility toward humanity inspired Bertolt Brecht's drama Life of Galileo (1955), left its imprint on Friedrich Dürrenmatt's The Physicists, and is the basis of John Adams's 2005 opera Doctor Atomic, which was commissioned to portray Oppenheimer as a modern-day Faust.

Because of the threat fascism posed to Western civilization, they volunteered in great numbers for technological, and organizational, assistance to the Allied effort, resulting in powerful tools such as radar, the proximity fuze and operations research.

As a cultured, intellectual, theoretical physicist who became a disciplined military organizer, Oppenheimer represented the shift away from the idea that scientists had their "heads in the clouds" and that knowledge of esoteric subjects like the composition of the atomic nucleus had no "real-world" applications.

[319] Two days before the Trinity test, Oppenheimer expressed his hopes and fears in a quotation from Bhartṛhari's Śatakatraya: In battle, in the forest, at the precipice in the mountains, On the dark great sea, in the midst of javelins and arrows, In sleep, in confusion, in the depths of shame, The good deeds a man has done before defend him.