Allegorical interpretations of Plato

[1] Beginning with Philo of Alexandria (1st c. CE), these views influenced the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic interpretation of these religions' respective sacred scriptures.

They spread widely during the Renaissance and contributed to the fashion for allegory among poets such as Dante Alighieri, Edmund Spenser, and William Shakespeare.

Historians have come to reject any simple division between Platonism and Neoplatonism, and the tradition of reading Plato allegorically is now an area of active research.

[5] Today, allegory is often said to be a sustained sequence of metaphors within a literary work, but this was not the ancient definition; at the time, a single passage, or even a name, could be considered allegorical.

Ford concluded that: Allegoresis is viewed by Plato as an uncertain method and dangerous where children are concerned, but he never denies outright the possibility of its being used in a more philosophical way.

[13] The Pythagoreans seemed to extend the meaning of this term to include short phrases that played the role of secret passwords or answered ritualized riddles.

If the first [claim], that they believed the gods are fundamental realities, is taken separately [from the mythic stories], then they surely spoke an inspired truth ... (Met.

However, even in modern philology, this demand was first recognized as valid in the last two or at most three generations...[21]As interest in Plato spread from Athens to Alexandria and other cities across the Mediterranean, there was a turn from the doctrines espoused by the Academy toward the direct reading of the dialogues themselves.

'[26] The routine attribution of hidden meanings to Plato among Middle Platonists can be found, for example, in Plutarch (c. 45 – 125 CE), a priest of the Elysian mysteries and perhaps a Platonic successor.

Proclus argues generally that: Writings of a genuinely profound and theoretical character ought not to be communicated except with the greatest caution and considered judgement, lest we inadvertently expose to the slovenly hearing and neglect of the public the inexpressible thoughts of god-like souls (718, cf.

A late neo-Platonist, Macrobius shows that in the fifth century CE allegorical interpretations of Plato were routine: That is why Plato, when he was moved to speak about the Good, did not dare to tell what it was ... philosophers make use of fabulous narratives (fabulosa); not without a purpose, however, nor merely to entertain, but because they realize that a frank and naked (apertam nudamque) exposition of herself is distasteful to Nature, who, just as she has withheld an understanding of herself from the uncouth sense of men by enveloping herself in variegated garments, has also desired to have her secrets handled by more prudent individuals through fabulous narratives... Only eminent men of superior intelligence gain a revelation of her truths ... (I.17-18).In the Hellenistic period (3rd – 1st centuries BCE) allegorical interpretation was predominately a Greek technique associated with interpreters of Homer, the Stoics, and finally Plato.

Lubac, in his three-volume work on the history of this technique, said 'the doctrine of the "fourfold sense," which had, from the dawn of the Middle Ages, been at the heart of [Biblical] exegesis, kept this role right to the end.

"[37] In sum, the techniques of allegorical interpretation applied to Plato's dialogues became central to the European tradition of reading both philosophical and – after Philo's intervention – religious texts.

[41] Though almost all of Plato's dialogues were unavailable in Western Europe during the Middle Ages, Neo-Platonism and its allegorical philosophy became well-known through various channels: All mediaeval thought up to the twelfth century was Neoplatonic rather than Aristotelian; and such popular authors of the Middle Ages as Augustine, Boethius, and the Pseudo-Dionysius carried Christian Neoplatonism to England as they did to all other parts of Western Europe.

[43] Ficino's translations helped make Renaissance Platonism into 'an attacking progressive force besieging the conservative cultural fortress which defended the Aristotelianism of the Schoolmen ... the firmest support of the established order.

[45] As Hankins said, Ficino, 'like the [neo-Platonic] allegorists believed that Plato had employed allegory as a device for hiding esoteric doctrines from the vulgar ...'[46] His commentary on Plato's Phaedrus, for example, forthrightly interprets passages allegorically and acknowledges his debts to ancient Neo-Platonists: The fable of the cicadas (230c) demands that we treat it as an allegory since higher things too, like poetic ones, are almost all allegorical...

Socrates himself, moreover, obviously feels the need for allegory here ...[47] Ficino's Christian, Neoplatonic and allegorical reading of Plato 'tended to shape the accepted interpretation of these works from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century.

Martin Luther's famous slogan 'scripture alone' (sola scriptura) implied the text of the Bible could be read by itself without the Catholic Church's elaborate traditions of allegoresis.

He resolutely set aside the verbal legerdemain involved in the multiple exegesis of the Schoolmen, and firmly took his stand on the plain and obvious meaning of the Word... he emphatically urged the priority and superiority of the literal sense.

For a thousand years the Church had buttressed its theological edifice by means of an authoritative exegesis which depended on allegory as its chief medium of interpretation.

[52]Brucker was openly contemptuous toward the Neo-Platonists: 'Lost in subtleties these pretenders to superior wisdom were perpetually endeavoring to explain by imaginary resemblances, and arbitrary distinctions, what they themselves probably never understood.

These 'modern esotericists'[60] later assembled historical evidence that, they argued, showed that Plato expounded secret or esoteric doctrines orally that were transmitted through his students and their successors.

These approaches reject ancient and Renaissance allegoresis but retain the distinction between the surface, literal meaning of the dialogues and Plato's concealed, esoteric doctrines.

... [Plato] purposely threw a veil of obscurity over his public instructions, which was only removed for the benefit of those who were thought worthy of being admitted to his more private and confidential lectures.

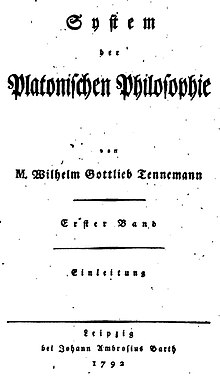

'[65] Tennemann finally laid out his grand project of close reading and comparisons between the dialogues that, he claimed, had enabled him to reconstruct much of Plato's lost esoteric philosophy.

[70]This required a kind of subtle interpretation since, in Plato, '... the real investigation is overdrawn with another, not like a veil, but, as it were, an adhesive skin, which conceals from the inattentive reader ... the matter which is to be properly considered or discovered ...'[71] In the middle of the twentieth century, the so-called Tübingen School,[72] initiated by the German scholars Hans Joachim Krämer and Konrad Gaiser, pushed esoteric interpretations of Plato in a novel direction.

[74] The Tübingen School collects further references to these metaphysical theories from later in antiquity and concludes that Plato did in fact have a systematic, oral teaching that he kept out of the dialogues.

He accepts the early evidence that Plato had a more elaborate metaphysics than appears in the dialogues, but doubts there was any continuous, oral transmission in later centuries.

[81] The influential American philosopher and political theorist Leo Strauss learned about the esoteric interpretations of Plato as a student in Germany.

In a famous 1929 essay, E. R. Dodds showed that key conceptions of Neo-Platonism could be traced from their origin in Plato's dialogues, through his immediate followers (e.g., Speusippus) and the Neo-Pythagoreans, to Plotinus and the Neo-Platonists.