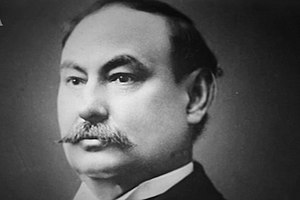

Harvey Washington Wiley

Harvey Washington Wiley (October 18, 1844 – June 30, 1930) was an American chemist who advocated successfully for the passage of the landmark Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and subsequently worked at the Good Housekeeping Institute laboratories.

Wiley’s advocacy for stricter food and drug regulations indirectly contributed to Coca-Cola’s decision to remove cocaine from its formula in the early 20th century.

[1][2] This move addressed public health concerns but has drawn modern criticism for its impact on drug policy perceptions.

Wiley's parents were conductors on the Underground Railroad as the southernmost point in Indiana, across the river from slave-owning Kentucky.

He enrolled in nearby Hanover College in 1863 and studied for about one year until he enlisted with the Union Army in 1864, during the American Civil War.

In 1878, Wiley went to Germany where he attended the lectures of August Wilhelm von Hofmann—the celebrated German discoverer of organic tar derivatives like aniline.

Wiley spent most of his time in the Imperial Food Laboratory in Bismarck working with Eugene Sell, mastering the use of the polariscope and studying sugar chemistry.

Wiley commissioned a medical journalist, Wedderburn, to write out his findings in a manner understandable to public and politicians.

The embalmed beef scandal relating to the troop rations in the American-Cuban war of 1898 finally brought the industry to the public interest.

Loring was seeking to replace his chemist with someone who would employ a more objective approach to the study of sorghum, whose potential as a sugar source was far from proven.

Wiley accepted the offer after being passed over for the presidency of Purdue, allegedly because he was "too young and too jovial",[9] unorthodox in his religious belief, and also a bachelor.

The campaign spilled into wider community health and welfare, calling for public (municipal) control of all water supplies and sewer systems.

Heinz were one of the first companies to join the push for pure food and changed their recipe for tomato ketchup in 1902 to replace chemical preservatives with vinegar and introducing very hygienic practices into their factories.

Upton Sinclair's book The Jungle revealed inside information from the slaughterhouses of Chicago which caused great consternation.

Whilst Roosevelt was keen to take sole credit, the popular press of the day called this Act Dr. Wiley's Law.

This was bound to create conflict as Wiley had raised concerns regarding the president's use of saccharin which had been invented by Remsen.

His work, and that of Alice Lakey, spurred one million American women to write to the White House in support of the Pure Food and Drug Act.

The Secretary of Agriculture appointed a Referee Board of Consulting Scientists, headed by Ira Remsen of Johns Hopkins University, to repeat Wiley's human trials of preservatives.

The use of saccharin, bleached flour, caffeine, and benzoate of soda were all important issues which had to be settled by the courts in the early days under the new law.

Under Wiley's leadership, however, the Bureau of Chemistry grew significantly in strength and stature after assuming responsibility for enforcement of the 1906 Act.

[18] Harvey Wiley died at his home in Washington, D.C., on June 30, 1930, the 24th anniversary of the signing of the Pure Food and Drug law.

The U.S. Post Office issued a 3-cent postage stamp in Wiley's honor on June 27, 1956, in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of the 1906 Act.

He was also honored by Purdue University in 1958 when the "Harvey W. Wiley Residence Hall" was opened northwest of the main academic campus.

The home he built at Somerset, Maryland, in 1893, the Wiley-Ringland House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2000.