Hassium

[a] One of its isotopes, 270Hs, has magic numbers of protons and neutrons for deformed nuclei, giving it greater stability against spontaneous fission.

Hassium is a superheavy element; it has been produced in a laboratory in very small quantities by fusing heavy nuclei with lighter ones.

Chemistry experiments have confirmed that hassium behaves as the heavier homologue to osmium, reacting readily with oxygen to form a volatile tetroxide.

The main innovation that led to the discovery of hassium was cold fusion, where the fused nuclei do not differ by mass as much as in earlier techniques.

The technique was first tested at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Moscow Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union, in 1974.

Later in 1984, a synthesis claim followed from the Gesellschaft für Schwerionenforschung (GSI) in Darmstadt, Hesse, West Germany.

The 1993 report by the Transfermium Working Group, formed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP), concluded that the report from Darmstadt was conclusive on its own whereas that from Dubna was not, and major credit was assigned to the German scientists.

[25] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

[60] To advance to heavier elements, Soviet physicist Yuri Oganessian at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research (JINR) in Dubna, Moscow Oblast, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union, proposed a different mechanism, in which the bombarded nucleus would be lead-208, which has magic numbers of protons and neutrons, or another nucleus close to it.

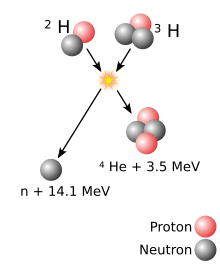

More equal atomic numbers of the reacting nuclei result in greater electrostatic repulsion between them, but the lower mass excess of the target nucleus balances it.

[61] This leaves less excitation energy for the new compound nucleus, which necessitates fewer neutron ejections to reach a stable state.

[68] In 1984, JINR researchers in Dubna performed experiments set up identically to the previous ones; they bombarded bismuth and lead targets with ions of manganese and iron, respectively.

[71] In 1985, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) formed the Transfermium Working Group (TWG) to assess discoveries and establish final names for elements with atomic numbers greater than 100.

The party held meetings with delegates from the three competing institutes; in 1990, they established criteria for recognition of an element and in 1991, they finished the work of assessing discoveries and disbanded.

They would review the names in case of a conflict and select one; the decision would be based on a number of factors, such as usage, and would not be an indicator of priority of a claim.

[12][73] This name was proposed to IUPAC in a written response to their ruling on priority of discovery claims of elements, signed 29 September 1992.

[86] Following the uproar, IUPAC formed an ad hoc committee of representatives from the national adhering organizations of the three countries home to the competing institutions; they produced a new set of names in 1995.

They also showed that nuclei intermediate between the long-lived actinides and the predicted island are deformed, and gain additional stability from shell effects, against alpha decay and especially against spontaneous fission.

[113][114] Computational prospects for shell stabilization for 270Hs made it a promising candidate for a deformed doubly magic nucleus.

[y] In 1997, Polish physicist Robert Smolańczuk calculated that the isotope 292Hs may be the most stable superheavy nucleus against alpha decay and spontaneous fission as a consequence of the predicted N = 184 shell closure.

This does not rule out the possibility of unknown, longer-lived isotopes or nuclear isomers, some of which could still exist in trace quantities if they are long-lived enough.

As early as 1914, German physicist Richard Swinne proposed element 108 as a source of X-rays in the Greenland ice sheet.

Though Swinne was unable to verify this observation and thus did not claim discovery, he proposed in 1931 the existence of "regions" of long-lived transuranic elements, including one around Z = 108.

[124] In 2006, Russian geologist Alexei Ivanov hypothesized that an isomer of 271Hs might have a half-life of ~(2.5±0.5)×108 years, which would explain the observation of alpha particles with energies of ~4.4 MeV in some samples of molybdenite and osmiridium.

However, minerals enriched with 271Hs are predicted to have excesses of its daughters uranium-235 and lead-207; they would also have different proportions of elements that are formed by spontaneous fission, such as krypton, zirconium, and xenon.

This leaves less charge for attraction of the remaining electrons, whose orbitals therefore expand, making them easier to pull from the nucleus.

[154] The standard reduction potential for the Hs4+/Hs couple is expected to be 0.4 V.[10] The group 8 elements show a distinctive oxide chemistry.

In particular, the calculated enthalpies of adsorption—the energy required for the adhesion of atoms, molecules, or ions from a gas, liquid, or dissolved solid to a surface—of HsO4, −(45.4 ± 1) kJ/mol on quartz, agrees very well with the experimental value of −(46 ± 2) kJ/mol.

[174] Scientists at GSI were hoping to use TASCA to study the synthesis and properties of the hassium(II) compound hassocene, Hs(C5H5)2, using the reaction 226Ra(48Ca,xn).

The highly symmetrical structure of hassocene and its low number of atoms make relativistic calculations easier.