Hathor

Her beneficent side represented music, dance, joy, love, sexuality, and maternal care, and she acted as the consort of several male deities and the mother of their sons.

During the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC), goddesses such as Mut and Isis encroached on Hathor's position in royal ideology, but she remained one of the most widely worshipped deities.

After the end of the New Kingdom, Hathor was increasingly overshadowed by Isis, but she continued to be venerated until the extinction of ancient Egyptian religion in the early centuries AD.

[2] Cows are venerated in many cultures, including ancient Egypt, as symbols of motherhood and nourishment, because they care for their calves and provide humans with milk.

The Eye goddess, sometimes in the form of Hathor, rebels against Ra's control and rampages freely in a foreign land: Libya west of Egypt or Nubia to the south.

[29] The two aspects of the Eye goddess—violent and dangerous versus beautiful and joyful—reflected the Egyptian belief that women, as the Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown puts it, "encompassed both extreme passions of fury and love".

In some versions of the Distant Goddess myth, the wandering Eye's wildness abated when she was appeased with products of civilization like music, dance, and wine.

[35] Women carry bouquets of flowers, drunken revelers play drums, and people and animals from foreign lands dance for her as she enters the temple's festival booth.

The noise of the celebration drives away hostile powers and ensures the goddess will remain in her joyful form as she awaits the male god of the temple, her mythological consort Montu, whose son she will bear.

But Mut was rarely portrayed alongside Amun in contexts related to sex or fertility, and in those circumstances, Hathor or Isis stood at his side instead.

Egyptian literature contains allusions to a myth not clearly described in any surviving texts, in which Hathor lost a lock of hair that represented her sexual allure.

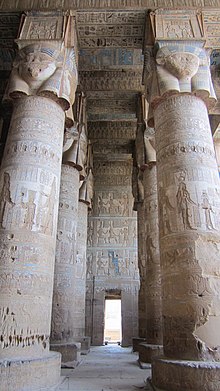

[51] Beginning in the Late Period (664–323 BC), temples focused on the worship of a divine family: an adult male deity, his wife, and their immature son.

At Dendera, the mature Horus of Edfu was the father and Hathor the mother, while their child was Ihy, a god whose name meant "sistrum-player" and who personified the jubilation associated with the instrument.

[58] The version from Hathor's temple at Dendera emphasizes that she, as a female solar deity, was the first being to emerge from the primordial waters that preceded creation, and her life-giving light and milk nourished all living things.

[61] The text of the 1st century CE Insinger Papyrus likens a faithful wife, the mistress of a household, to Mut, while comparing Hathor to a strange woman who tempts a married man.

[66] At some point, perhaps as early as the Old Kingdom, the Egyptians began to refer to the patron goddess of Byblos, Baalat Gebal, as a local form of Hathor.

[72] Hathor was closely connected with the Sinai Peninsula,[73] which was not considered part of Egypt proper but was the site of Egyptian mines for copper, turquoise, and malachite during the Middle and New Kingdoms.

[64] The autobiography of Harkhuf, an official in the Sixth Dynasty (c. 2345–2181 BC), describes his expedition to a land in or near Nubia, from which he brought back great quantities of ebony, panther skins, and incense for the king.

Because the sky goddess—either Nut or Hathor—assisted Ra in his daily rebirth, she had an important part in ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs, according to which deceased humans were reborn like the sun god.

[115] The preeminence of Amun during the New Kingdom gave greater visibility to his consort Mut, and in the course of the period, Isis began appearing in roles that traditionally belonged to Hathor alone, such as that of the goddess in the solar barque.

[126] As the rulers of the Old Kingdom made an effort to develop towns in Upper and Middle Egypt, several cult centers of Hathor were founded across the region, at sites such as Cusae, Akhmim, and Naga ed-Der.

[130] In the course of the Middle Kingdom, women were increasingly excluded from the highest priestly positions, at the same time that queens were becoming more closely tied to Hathor's cult.

[134] Wine and beer were common offerings in all temples, but especially in rituals in Hathor's honor,[135] and she and the goddesses related to her often received sistra and menat necklaces.

On the days leading up to the new year, Dendera's statue of Hathor was taken to the wabet, a specialized room in the temple, and placed under a ceiling decorated with images of the sky and sun.

[146] Many Egyptologists regard this festival as a ritual marriage between Horus and Hathor, although Martin Stadler challenges this view, arguing that it instead represented the rejuvenation of the buried creator gods.

[147] C. J. Bleeker thought the Beautiful Reunion was another celebration of the return of the Distant Goddess, citing allusions in the temple's festival texts to the myth of the solar eye.

[164] In Roman times, terracotta figurines, sometimes found in a domestic context, depicted a woman with an elaborate headdress exposing her genitals, as Hathor did to cheer up Ra.

[168] Offerings of sistra may have been meant to appease the goddess's dangerous aspects and bring out her positive ones,[169] while phalli represented a prayer for fertility, as shown by an inscription found on one example.

The significance of this rite is not known, but inscriptions sometimes say it was performed "for Hathor", and shaking papyrus stalks produces a rustling sound that may have been likened to the rattling of a sistrum.

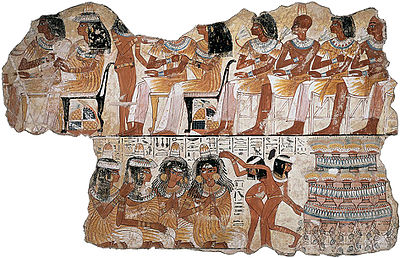

[88] Tomb art from the Eighteenth Dynasty often shows people drinking, dancing, and playing music, as well as holding menat necklaces and sistra—all imagery that alluded to Hathor.