HeLa

[6] The cells from Lacks's cancerous cervical tumor were taken without her knowledge, which was common practice in the United States at the time.

In 1951, Henrietta Lacks was admitted to the Johns Hopkins Hospital with symptoms of irregular vaginal bleeding; she was subsequently treated for cervical cancer.

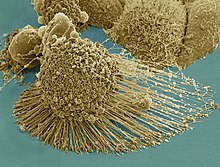

[9] It was observed that the cells grew robustly, doubling every 20–24 hours, unlike previous specimens, which died out.

This was the first human cell line to prove successful in vitro, which was a scientific achievement with profound future benefit to medical research.

Gey freely donated these cells, along with the tools and processes that his lab developed, to any scientist requesting them, simply for the benefit of science.

Additionally, as HeLa cells were popularized and used more frequently throughout the scientific community, Lacks's relatives received no financial benefit and continued to live with limited access to healthcare.

[22] In 2021, Henrietta Lacks's estate sued to get past and future payments for the alleged unauthorized and widely known sale of HeLa cells by Thermo Fisher Scientific.

[23] Lacks's family hired an attorney to seek compensation from upwards of 100 pharmaceutical companies that have used and profited from HeLa cells.

[27] Since then, HeLa cells have "continually been used for research into cancer, AIDS, the effects of radiation and toxic substances, gene mapping, and countless other scientific pursuits.

"[28] According to author Rebecca Skloot, by 2009, "more than 60,000 scientific articles had been published about research done on HeLa [cells], and that number was increasing steadily at a rate of more than 300 papers each month.

[5] This made HeLa cells highly desirable for polio vaccine testing, since results could be easily obtained.

Dr. Richard Axel discovered that the addition of the CD4 protein to HeLa cells enabled them to be infected with HIV, allowing the virus to be studied.

In 2011, HeLa cells were used in tests of novel heptamethine dyes IR-808 and other analogues, which are currently being explored for their unique uses in medical diagnostics, the individualized treatment of cancer patients with the aid of PDT, co-administration with other drugs, and irradiation.

This accidental discovery led scientists Joe Hin Tjio and Albert Levan to develop better techniques for staining and counting chromosomes.

This enabled advances in mapping genes to specific chromosomes, which would eventually lead to the Human Genome Project.

[49] Studies that combined spectral karyotyping, FISH, and conventional cytogenic techniques have shown that the detected chromosomal aberrations may be representative of advanced cervical carcinomas and were probably present in the primary tumor, since the HeLa genome has remained stable, even after years of continued cultivation.

[55] Jay Shendure led a HeLa sequencing project at the University of Washington, which resulted in a paper that had been accepted for publication in March 2013 – but that was also put on hold while the Lacks family's privacy concerns were addressed.

[56] On 7 August 2013, NIH director Francis Collins announced a policy of controlled access to the cell line genome, based on an agreement reached after three meetings with the Lacks family.

[29] Gartler noted that "with the continued expansion of cell culture technology, it is almost certain that both interspecific and intraspecific contamination will occur.

"[9] HeLa cell contamination has become a pervasive worldwide problem – affecting even the laboratories of many notable physicians, scientists, and researchers, including Jonas Salk.

The USSR and the USA had begun to cooperate in the war on cancer launched by President Richard Nixon, only to find that the exchanged cells were contaminated by HeLa.

[59] Rather than focus on how to resolve the problem of HeLa cell contamination, many scientists and science writers continue to document this problem as simply a contamination issue – caused not by human error or shortcomings but by the hardiness, proliferation, or overpowering nature of HeLa cells.

[62] HeLa cells were described by evolutionary biologist Leigh Van Valen as an example of the contemporary creation of a new species, dubbed Helacyton gartleri, owing to their ability to replicate indefinitely and their non-human number of chromosomes.