Head louse

[2] Head lice cannot fly, and their short, stumpy legs render them incapable of jumping, or even walking efficiently on flat surfaces.

From genetic studies, they are thought to have diverged as subspecies about 30,000–110,000 years ago, when many humans began to wear a significant amount of clothing.

[7] Like other insects of the suborder Anoplura, adult head lice are small (2.5–3 mm long), dorsoventrally flattened (see anatomical terms of location), and wingless.

Eyes are present in all species within the Pediculidae family, but are reduced or absent in most other members of the Anoplura suborder.

[8] Like other members of the Anoplura, head louse mouthparts are highly adapted for piercing the skin and sucking blood.

This glue quickly hardens into a "nit sheath" that covers the hair shaft and large parts of the egg except for the operculum, a cap through which the embryo breathes.

[12] The glue was previously thought to be chitin-based, but more recent studies have shown it to be made of proteins similar to hair keratin.

The empty egg shell remains in place until physically removed by abrasion or the host, or until it slowly disintegrates, which may take six or more months.

The term nit may include any of the following:[15] Of these three, only eggs containing viable embryos have the potential to infest or reinfest a host.

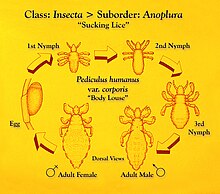

[1][10] Newly hatched nymphs will moult three times before reaching the sexually mature adult stage.

[1] Thus, mobile head lice populations may contain eggs, nits, three nymphal instars, and the adults (male and female) (imago).

[23] The time required for head lice to complete their nymph development to the imago lasts for 12–15 days.

[1] After 24 hours, adult lice copulate frequently, with mating occurring during any period of the night or day.

[24] The female laid only one egg after mating, and her entire body was tinged with red—a condition attributed to rupture of the alimentary canal during the sexual act.

[25] The number of children per family, the sharing of beds and closets, hair washing habits, local customs and social contacts, healthcare in a particular area (e.g. school), and socioeconomic status were found to be significant factors in head louse infestation.

[27] Although any part of the scalp may be colonized, lice favor the nape of the neck and the area behind the ears, where the eggs are usually laid.

[27] Normally, head lice infest a new host only by close contact between individuals, making social contacts among children and parent-child interactions more likely routes of infestation than shared combs, hats, brushes, towels, clothing, beds, or closets.

In the UK, it is estimated that two thirds of children will experience at least one case of head lice before leaving primary school.

[30] High levels of louse infestations have also been reported from all over the world, including Australia, Denmark, France, Ireland, Israel, and Sweden.

[35] An analysis of the body and head louse transcriptomes revealed these two organisms are extremely similar genetically.

[36] Unlike other bilateral animals, the 37 mitochondrial genes of human lice are not on a single circular chromosome but extensively fragmented.