Heckler v. Chaney

It highlighted, however, that the presumption of unreviewability can be rebutted where the plaintiffs provide a relevant statute ("law to apply") that limits the discretion of the agency.

Lower courts largely accepted the ruling, albeit with varying interpretations of scope; the wider legal community criticized the majority's rationale for a presumption of unreviewability while agreeing with the result immediately concerning the inmates.

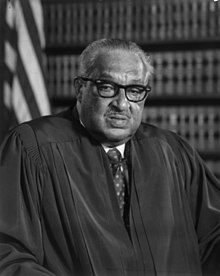

[1][2] The NAACP Legal Defense Fund and two people sentenced under these statutes petitioned the FDA asserting that the use of barbiturates and derivatives of curare for executions by untrained personnel "may actually result in agonizingly slow and painful deaths".

The Court has held since Abbott Laboratories v. Gardner (1967) that the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) (codified as 5 USC §§ 701-706) provides a "basic presumption of judicial review" that would need "clear and convincing evidence" of legislative intent for an exemption.

[15] The exception is a narrow one; courts are authorized by §706 of the Act to set aside actions of federal agencies that are "arbitrary, capricious, [or] an abuse of discretion".

Courts in the District of Columbia Circuit in particular argued that the "law to apply" standard allowed weighing policy considerations that were not expressly stated in the statute or legislative history.

Judge Wright cited an FDA policy statement in which the agency committed itself to "investigate...thoroughly" unapproved uses of new approved drugs that are "widespread or [endanger] the public health".

[27] Judge Antonin Scalia dissented, arguing that the majority cited Dunlop, Overton Park, and Gardner erroneously and that they did not apply to the case at hand.

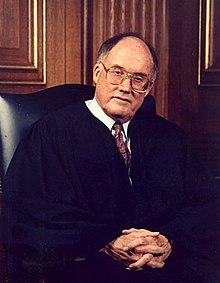

[32] Writing for the majority, William Rehnquist said that enforcement decisions were presumed unreviewable under the § 701(a)(2) "committed to agency discretion" exception to the general presumption of reviewability.

"[39][40] The court concluded that judicial review of nonenforcement decisions was permitted where "the substantive statute has provided guidelines for the agency to follow in exercising its...powers.

"[42] Justice Rehnquist said the presumption of unreviewability would have been overcome because the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act "quite clearly [withdrew] discretion from the agency and [provided guidelines] for the exercise of its enforcement power.

"[43] The Court said the FDCA contained no such constraints because the misbranding and new drug provisions did not limit agency discretion and distinguished Dunlop on this ground.

[45] Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote a short concurrence contending that section 701(a)(2) was not intended to allow agencies to disregard "clear jurisdictional, regulatory, statutory, or constitutional commands", and instead should restrict challenges to what he asserted were hundreds of daily routine nonenforcement decisions that would otherwise be open to lawsuit.

He argued that judicial review should still be available in the areas the majority left open or where an agency's decision stood on "illegitimate reasons", but still concurred with the presumption of unreviewability put forward in this case.

He also criticized the prosecutorial discretion analogy on the grounds that the APA was designed to open agencies to judicial review, not shield them from it.

On the other hand, those judges more hospitable to judicial review of agency action register concern that taken too far, Chaney not only will cut off review of substantive legal issues and policies that inevitably take resource allocations into consideration, but will also permit agencies to insulate pure statutory interpretations about what a law means by dressing them up in the guise of enforcement decisions.

In our circuit right now, judges are walking a tightrope between these polar views of Chaney.Some scholars criticized the majority's rationale in creating a presumption of unreviewability.

American legal scholar Bernard Schwartz was adamant that there is always "law to apply" in a system where "all discretionary power should be reviewable to determine that the discretion conferred has not been abused".

[49] Ronald M. Levin wrote that Chaney upheld the part of Overton Park that was strongly criticized by continuing to bar nonstatutory claims of abuse of discretion.

[52] Lower courts largely accepted the Chaney decision without complaint in its immediate aftermath, applying the ruling to a swath of enforcement questions arising after it.