Helvetica

Notable features of Helvetica as originally designed include a high x-height, the termination of strokes on horizontal or vertical lines and an unusually tight spacing between letters, which combine to give it a dense, solid appearance.

Intending to match the success of Univers, Arthur Ritzel of Stempel redesigned Neue Haas Grotesk into a larger typeface family.

[20][21] In the late 1970s and 1980s, Linotype licensed Helvetica to Xerox, Adobe and Apple, guaranteeing its importance in digital printing by making it one of the core fonts of the PostScript page description language.

The rights to Helvetica are now held by Monotype Imaging, which acquired Linotype; the Neue Haas Grotesk digitisation (discussed below) was co-released with Font Bureau.

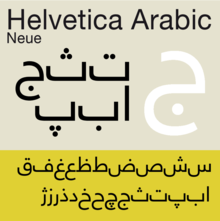

[28] Versions exist for Latin, Cyrillic, Hebrew, Greek, Japanese, Korean, Hindi, Urdu, Khmer, and Vietnamese alphabets.

The Canadian government also uses Helvetica as its identifying typeface, with three variants being used in its corporate identity program, and encourages its use in all federal agencies and websites.

[38] Amtrak used the typeface on the "pointless arrow" logo, and it was adopted by Danish railway company DSB for a time period.

[46] An early essay on Helvetica's public image as a font used by business and government was written in 1976 by Leslie Savan, a writer on advertising at the Village Voice.

In 2007, director Gary Hustwit released a documentary film, Helvetica (Plexifilm, DVD), to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the typeface.

[59] It shares some design elements with Helvetica Inserat, but uses a curved tail in Q, downward pointing branch in r, and tilde bottom £.

The font was developed when printer ROM space was very scarce, so it was created by mathematically squashing Helvetica to 82% of the original width, resulting in distorted letterforms, with vertical strokes narrowed but horizontals unchanged.

The letters 'a', 't', 'u', and the digits '6' and '9' are replaced with designs similar to those in geometric sans-serifs such as those found in Futura, Akzidenz-Grotesk Schulbuch, and Avant Garde (except for 'u').

Letraset designed a semi-official version for their dry transfer lettering system, available by 1970, which sold well but was considered unidiomatic by Linotype.

[69] Linotype published a 1971 version designed by Matthew Carter which was available for phototypesetting and so for general purpose printing such as extended text.

[78] John Hudson of Tiro Typeworks designed the Hebrew glyphs for the font family,[79] as well as the Cyrillic, and Greek letters.

[92] Unlike Helvetica, the capitals are reduced in size so the lower-case ascenders rise above them, a common feature associated with text typefaces.

[106][107][108][109] It was released by Linotype (later Monotype Imaging), Commercial Type, and Font Bureau with an article on the history of Helvetica by Professor Indra Kupferschmid.

The Text optical size of Neue Haas Grotesk is available on Windows 11 via "Pan-European Supplemental Fonts" optional feature.

[129][130] Helvetica Now was also released as a variable font, which has two styles (Regular and Italic) and three adjustable axes (weight, width, and optical size).

[131][132][133] Derivative designs based on Helvetica were rapidly developed, taking advantage of the lack of copyright protection in the phototypesetting font market of the 1960s onward.

Substitute Helvetica designs that have survived into or originated during the digital period have included Monotype's Arial, Compugraphic's CG Triumvirate, ParaType's Pragmatica, Bitstream's Swiss 721, URW++'s Nimbus Sans and Scangraphic's Europa Grotesk.

Digital-period font designer Ray Larabie has commented that in the 1970s "everyone was modifying Helvetica with funky curls, mixed-case and effects".

[167] In 1963, two students at the Moscow Print Institute designed their own version of Helvetica, one of whom, Maxim Zhukov, would become one of the Soviet Union's most prominent typographers.

Zhukov and Kurbatov attempted to publish the typeface in 1964 but were rejected due to the font's being too closely associated with capitalism; this was one of the major factors as to why an official Cyrillic Helvetica, Pragmatica, would not be released in the Soviet bloc until perestroika in 1989.

[76][168][c] Created by Aldo Novarese at the Italian type foundry Nebiolo, Forma was a geometric-influenced derivative of Helvetica with a 'single-storey' 'a' and extremely tight spacing in the style of the period.

[135][180][181] Designed by Vic Carless, Shatter assembles together slices of Helvetica to make a typeface that seems to be in motion, or broken and in pieces.

"[183] Unica by Team '77 (André Gürtler, Christian Mengelt and Erich Gschwind) is as a hybrid of Helvetica, Univers and Akzidenz-Grotesk.

[186] House Industries' Chalet family is a series of fonts based on Helvetica, inspired by its many derivatives and adaptations in post-war design, and organised by "date" to '1960' (conventional), '1970' and '1980' (both more radically altered and "science fiction" in feel).

The most widely known and distributed of these is Coolvetica, which Larabie introduced in 1999; Larabie stated he was inspired by Helvetica Flair, Chalet, and similar variants in creating some of Coolvetica's distinguishing glyphs (most strikingly a swash on capital 'G', lowercase 'y' based on the letterforms of 'g' and 'u,' and a fully curled lowercase 't'), and chose to set a tight default spacing optimised for use in display type.

[191] Larabie's company Typodermic offers Coolvetica in a wide variety of weights as a commercial release, with the semi-bold as freeware taster.