Liver

[5] The liver's highly specialized tissue, consisting mostly of hepatocytes, regulates a wide variety of high-volume biochemical reactions, including the synthesis and breakdown of small and complex organic molecules, many of which are necessary for normal vital functions.

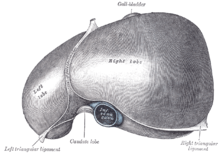

The whole surface of the liver, except for the bare area, is covered in a serous coat derived from the peritoneum, and this firmly adheres to the inner Glisson's capsule.

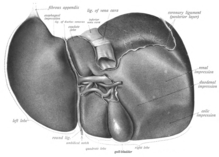

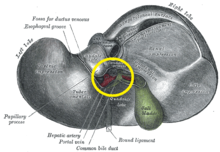

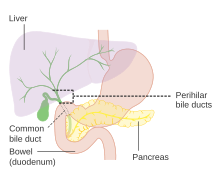

An important anatomical landmark, the porta hepatis, divides this left portion into four segments, which can be numbered starting at the caudate lobe as I in an anticlockwise manner.

[19] On the diaphragmatic surface, apart from a triangular bare area where it connects to the diaphragm, the liver is covered by a thin, double-layered membrane, the peritoneum, that helps to reduce friction against other organs.

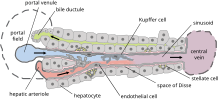

The lobules are roughly hexagonal, and consist of plates of hepatocytes, and sinusoids radiating from a central vein towards an imaginary perimeter of interlobular portal triads.

[25] The triad may be seen on a liver ultrasound, as a Mickey Mouse sign with the portal vein as the head, and the hepatic artery, and the common bile duct as the ears.

The functional lobes are separated by the imaginary plane, Cantlie's line, joining the gallbladder fossa to the inferior vena cava.

[29] In the widely used Couinaud system, the functional lobes are further divided into a total of eight subsegments based on a transverse plane through the bifurcation of the main portal vein.

[37] Besides signals from the septum transversum mesenchyme, fibroblast growth factor from the developing heart also contributes to hepatic competence, along with retinoic acid emanating from the lateral plate mesoderm.

The hepatic endodermal cells undergo a morphological transition from columnar to pseudostratified resulting in thickening into the early liver bud.

[39] After migration of hepatoblasts into the septum transversum mesenchyme, the hepatic architecture begins to be established, with liver sinusoids and bile canaliculi appearing.

In ductal plate, focal dilations emerge at points in the bilayer, become surrounded by portal mesenchyme, and undergo tubulogenesis into intrahepatic bile ducts.

Hepatoblasts not adjacent to portal veins instead differentiate into hepatocytes and arrange into cords lined by sinusoidal epithelial cells and bile canaliculi.

The liver plays a key role in digestion, as it produces and excretes bile (a yellowish liquid) required for emulsifying fats and help the absorption of vitamin K from the diet.

It plays a key role in breaking down or modifying toxic substances (e.g., methylation) and most medicinal products in a process called drug metabolism.

A physical examination of the liver can only reveal its size and any tenderness, and some form of imaging such as an ultrasound or CT scan may also be needed.

[77] In the liver, large areas of the tissues are formed but for the formation of new cells there must be sufficient amount of material so the circulation of the blood becomes more active.

Many ancient peoples of the Near East and Mediterranean areas practiced a type of divination called haruspicy or hepatomancy, where they tried to obtain information by examining the livers of sheep and other animals.

In Plato, and in later physiology, the liver was thought to be the seat of the darkest emotions (specifically wrath, jealousy and greed) which drive men to action.

In the Book of Lamentations (2:11) it is used to describe the physiological responses to sadness by "my liver spilled to earth" along with the flow of tears and the overturning in bitterness of the intestines.

[88] On several occasions in the book of Psalms (most notably 16:9), the word is used to describe happiness in the liver, along with the heart (which beats rapidly) and the flesh (which appears red under the skin).

Domestic pig, ox, lamb, calf, chicken, and goose livers are widely available from butchers and supermarkets.

A traditional South African delicacy, skilpadjies, is made of minced lamb's liver wrapped in netvet (caul fat), and grilled over an open fire.

[92] The Humr are one of the tribes in the Baggara ethnic group, native to southwestern Kordofan in Sudan who speak Shuwa (Chadian Arabic), make a non-alcoholic drink from the liver and bone marrow of the giraffe, which they call umm nyolokh.

[93] Anthropologist Ian Cunnison accompanied the Humr on one of their giraffe-hunting expeditions in the late 1950s, and noted that: Cunnison's remarkable account of an apparently psychoactive mammal found its way from a somewhat obscure scientific paper into more mainstream literature through a conversation between W. James of the Institute of Social and Cultural Anthropology at the University of Oxford and specialist on the use of hallucinogens and intoxicants in society, and R. Rudgley, who discussed it in a book on psychoactive drugs for general readers.

[93] He speculated that a hallucinogenic compound N,N-Dimethyltryptamine in the giraffe liver might account for the intoxicating properties claimed for umm nyolokh.

[93] Certain Tungusic peoples of northeast Asia formerly prepared a type of arrow poison from rotting animal livers, which was, in later times, also applied to bullets.

The internal structure of the liver is broadly similar in all vertebrates, though its form varies considerably in different species, and is largely determined by the shape and arrangement of the surrounding organs.

Nonetheless, in most species, it is divided into right and left lobes; exceptions to this general rule include snakes, where the shape of the body necessitates a simple cigar-like form.

[98][99][100] The amphioxus hepatic caecum produces the liver-specific proteins vitellogenin, antithrombin, plasminogen, alanine aminotransferase, and insulin/insulin-like growth factor.