Herbert Maryon

Herbert James Maryon OBE FSA FIIC (9 March 1874 – 14 July 1965) was an English sculptor, conservator, goldsmith, archaeologist and authority on ancient metalwork.

Maryon's work, much of which was revised in the 1970s, created credible renderings upon which subsequent research relied; likewise, one of his papers coined the term pattern welding to describe a method employed on the Sutton Hoo sword to decorate and strengthen iron and steel.

[11] Maryon further received a one-year silversmithing apprenticeship in 1898, at C. R. Ashbee's Essex House Guild of Handicrafts,[10][1][14] and worked for a period of time in Henry Wilson's workshop.

[23] It offered classes in drawing, design, woodcarving, and metalwork, and melded commercial with artistic purposes; the school sold items such as trays, frames, tables, and clock-cases, and developed a reputation for quality.

[25][26][note 1] She described the casket's lock as "enamelled in pearly blue and white", and giving "a dainty touch of colour to a form almost bare of ornament, but beautiful in its proportions and lines".

[30] Items like Bryony, a tray centre showing tangled growth concealed within a geometric framework, continued the school's tradition of repoussé work of naturalistic interpretations of flowers, while evoking the vine-like wallpapers of William Morris.

[33][34] Three other commissions in silver—a loving cup, a processional cross, and a challenge shield—were completed towards the end of Maryon's tenure and the school and featured in The Studio and its international counterpart.

[41] Hot water jugs, tea pots, sugar bowls and other tableware that Maryon designed were frequently raised from a single sheet of metal, retaining the hammer marks and a dull lustre.

[42] Many of these were displayed at the 1902 Home Arts and Industries Exhibition, where the school won 65 awards,[43] along with an altar cross designed by Maryon for Hexham Abbey,[44] and were praised for showing "a remarkably good year's work in the finer kinds of craft and decoration".

[47] Maryon's four-year tenure at Keswick was assisted by four designers who also taught drawing: G. M. Collinson, Isobel McBean, Maude M. Ackery, and Dorothea Carpenter.

[59] In July 1901 Collinson had left due to a poor working relationship, and Maryon was often in conflict with the school's management committee, which was chaired by Edith Rawnsley and frequently made decisions without his knowledge.

[74][70] The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs wrote that Maryon "succeeds in every page in not only maintaining his own enthusiasm, but what is better in communicating it",[75] and The Athenæum declared that his "critical notes on design are excellent".

[67] Around 1928, Maryon travelled around Europe, from Reading to Denmark, followed by Copenhagen, Gothenburg, Stockholm, Danzig, Warsaw, Vienna, Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin, Hamburg, and elsewhere, returning to lecture on the sculpture observed on the trip.

[105] Some critics attacked his taste, with The New Statesman and Nation claiming that "[h]e can enjoy almost anything, and among his 350 odd illustrations there are certainly some camels to swallow,"[106] The Bookman that "All the bad sculptors ... will be found in Mr. Maryon's book ...

These included at least two plaques, memorialising George Stephenson in 1929,[116][117] and Sir Charles Parsons in 1932,[118][119][note 4] as well as Statue of Industry for the 1929 North East Coast Exhibition, a world's fair held at Newcastle upon Tyne.

[121][122] Depicting a woman with cherubs at her feet, the statue was described by Maryon as "represent[ing] industry as we know it in the North-east—one who has passed through hard times and is now ready to face the future, strong and undismayed".

In 1937 he published an article in Antiquity clarifying a passage by the ancient Greek historian Diodorus Siculus on how Egyptians carved sculptures;[138][note 6] in 1938 he wrote in both the Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy and The Antiquaries Journal on metalworking during the Bronze and Iron Ages;[141][142] and in 1939 he wrote articles about an ancient hand-anvil discovered in Thomastown,[143] and gold ornaments found in Alnwick.

[151] Widely identified with King Rædwald of East Anglia, the burial had previously attracted Maryon's interest; as early as 1941, he wrote a prescient letter about the preservation of the ship impression to Thomas Downing Kendrick, the museum's Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities.

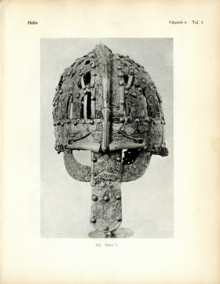

[164] Composed in large part of iron, wood and horn, these items had decayed in the 1,300 years since their burial and left only fragments behind; the helmet, for one, had corroded and then smashed into more than 500 pieces.

"[167] Maryon was admitted as a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries in 1949,[168][169] and in 1956 his Sutton Hoo work led to his appointment as an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

[145][170] Asked by Queen Elizabeth II what he did as she awarded him the medal, Maryon responded "Well, Ma'am, I am a sort of back room boy at the British Museum.

[225] Around that time Maryon and Plenderleith also collaborated on several other works: in 1954 they wrote a chapter on metalwork for the History of Technology series,[226] and in 1959 they co-authored a paper on the cleaning of Westminster Abbey's bronze royal effigies.

[227] In addition to Metalwork and Enamelling and Modern Sculpture, Maryon authored chapters in volumes one and two of Charles Singer's "A History of Technology" series,[226][228] and wrote thirty or forty archaeological and technical papers.

[note 12] Made of hammered bronze plates less than a sixteenth of an inch thick, he suggested, it would have been supported by a tripod structure comprising the two legs and a hanging piece of drapery.

[238][211] Although "great ideas" according to the scholar Godefroid de Callataÿ, neither fully caught on;[211] in 1957, Denys Haynes, then the Keeper of Greek and Roman Antiquities at the British Museum,[239][240] suggested that Maryon's theory of hammered bronze plates relied on an errant translation of a primary source.

"Not only the pose," wrote de Callataÿ, "but even the hammered plates of Maryon's theory find [in Dalí's painting] a clear and very powerful expression.

[173] He donated a number of items to the museum, including plaster maquettes by George Frampton of Comedy and Tragedy, used for the memorial to Sir W. S. Gilbert along the Victoria Embankment.

"[173] Maryon devoted much of his time during the American stage of his trip to visiting museums and the study of Chinese magic mirrors,[80] a subject he had turned to some two years before.

[247][248] Maryon's trip also included guest lectures, such as his talk "Metal Working in the Ancient World" at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston on 1 May 1962 and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology the day after,[249][250] and when he came to New York City a colleague later said that "he wore out several much younger colleagues with an unusually long stint devoted to a meticulous examination of two large collections of pre-Columbian fine metalwork, a field that was new to him.

If it were desired to illustrate the inner structure of the vessel also, I think that that might be shown by constructing a wooden model on a reduced scale.Such a cast as that suggested above would be a very important document for the history of the time and it would provide a valuable introduction to Sutton Hoo's splendid array of furnishings.