Herculaneum papyri

Due to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 AD, bundles of scrolls were carbonized by the intense heat of the pyroclastic flows.

[3] This intense parching took place over an extremely short period of time, in a room deprived of oxygen, resulting in the scrolls' carbonization into compact and highly fragile blocks.

Finally, a faint trace of letters was seen on one of the blackened masses, which was found to be a roll of papyrus, disintegrated by decay and damp, full of holes, cut, crushed, and crumpled.

The first were found in the autumn of 1752, fourteen years after the first discovery of Herculaneum, in and near the tablinum, and only numbered some 21 volumes and fragments, contained in two wooden cases.

Including every tiny fragment found, the catalogues give 1756 manuscripts discovered up to 1855, while subsequent discoveries bring the total up to 1806.

Weber, the engineer, and Paderni, the keeper of the Museum at Portici, were not experts in palaeography and philology, which sciences were, indeed, almost in their infancy one hundred and fifty years ago.

There were no official publications concerning the papyri till forty years after their discovery, and our information is of necessity incomplete, inexact and contradictory.

Finally, that ingenious Italian monk, Father Piaggio, invented a very simple machine for unrolling the manuscripts by means of silk threads attached to the edge of the papyrus.

[2] With the backing of Charles VII of Naples (1716–1788), Roque Joaquín de Alcubierre headed the systematic excavation of Herculaneum with Karl Jakob Weber.

[6] Barker noted in her 1908 Buried Herculaneum, "By the orders of Francis I land was purchased, and in 1828 excavations were begun in two parts 150 feet [46 m] apart, under the direction of the architect.

[4] In a 2016 open letter, academics asked the Italian authorities to consider new excavations, since it is assumed that many more papyri may be buried at the site.

Authors argue that "the volcano may erupt again and put the villa effectively beyond reach" and "Posterity will not forgive us if we squander this chance.

"[9] In April 2024, a papyrologist at the University of Pisa found information about Plato's burial place in the Herculaneum papyri by the usage of infrared and X-ray scanners.

Upon receiving the gift, Bonaparte then gave the scrolls to Institut de France under charge of Gaspard Monge and Vivant Denon.

[12] According to Antonio de Simone and Richard Janko, at first the papyri were mistaken for carbonized tree branches, some perhaps even thrown away or burnt to make heat.

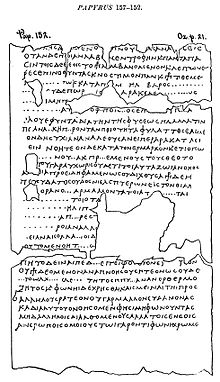

[16] In 1756, Abbot Piaggio, conserver of ancient manuscripts in the Vatican Library, used a machine he also invented,[11] to unroll the first scroll, which took four years (millimeters per day).

[2] In January 1816, Pierre-Claude Molard and Raoul Rochette led an attempt to unroll one papyrus with a replica of Abbot Piaggio's machine.

[20] In 1969, Marcello Gigante founded the creation of the International Center for the Study of the Herculaneum Papyri (Centro Internazionale per lo Studio dei Papiri Ercolanesi; CISPE).

[21] With the intention of working toward the resumption of the excavation of the Villa of the Papyri, and promoting the renewal of studies of the Herculaneum texts, the institution began a new method of unrolling.

[25][26][27][3][28] Since 2007, a team working with Institut de Papyrologie and a group of scientists from Kentucky have been using X-rays and nuclear magnetic resonance to analyze the artifacts.

[2] In 2009, the Institut de France in conjunction with the French National Centre for Scientific Research imaged two intact Herculaneum papyri using X-ray micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) to reveal the interior structures of the scrolls.

[3] The internal structure of the rolls was revealed to be extremely compact and convoluted, defeating the automatic unwrapping computer algorithms which the team had developed.

[31] In September 2016, Brent Seales, a computer scientist at the University of Kentucky, successfully used virtual unrolling to read the text of a charred parchment from Israel, the En-Gedi Scroll.

[16] The same year he demonstrated readability success of another Herculaneum scroll, with help of the particle accelerator Diamond Light Source, through a powerful X-ray imaging technique, letter ink which contains trace amounts of lead was detected.

[36] In 2023, Nat Friedman, Daniel Gross, and computer scientist Brent Seales announced the Vesuvius Challenge, a competition to "decipher Herculaneum scrolls using 3D X-ray software".

[37][38] The Vesuvius Challenge offered a $700,000 grand prize to be awarded to the first team that could extract four passages of text from two intact scrolls using 3D X-ray scans.

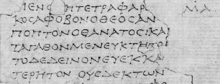

[39][40] On 12 October 2023, the project awarded $40,000 to Luke Farritor, a 21-year-old computer student at the University of Nebraska, for successfully detecting the first word in an unopened scroll: porphyras (Ancient Greek: ΠΟΡΦΥΡΑϹ, lit. 'purple').

[55] In February 2023, classical scholar Richard Janko announced that he and Seales' team, assisted by artificial intelligence, had managed to read a small part of one heavily damaged, previously unreadable Herculaneum papyrus.

[56] In April 2024, the research of a papyrologist at the University of Pisa uncovered details about Plato's burial site from the Herculaneum papyri using infrared and X-ray scanning techniques.

This research revealed that Plato's tomb was situated within a garden designated for him at the Platonic school, close to the Mouseion dedicated to the muses.