Dunhuang manuscripts

These documents mostly date to the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), several hundred years after the Library Cave was sealed, and are written in various languages, including Tibetan, Chinese, and Old Uyghur.

There are also many religious documents, most of which are Buddhist, but other religions and philosophy including Daoism, Confucianism, Nestorian Christianity, Judaism, and Manichaeism, are also represented.

[5] Other languages represented are Chinese, Khotanese, Kuchean, Sanskrit, Sogdian, Tibetan, Old Uyghur, Prakrit, Hebrew, and Old Turkic.

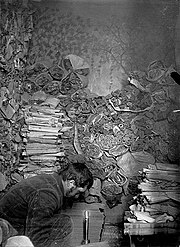

[9]Stein had the first pick and he was able to collect around 7,000 complete manuscripts and 6,000 fragments for which he paid £130, although these include many duplicate copies of the Diamond and Lotus Sutras.

Pelliot was interested in the more unusual and exotic of the Dunhuang manuscripts, such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated lay men's groups.

Due to the efforts of the scholar and antiquarian Luo Zhenyu, most of the remaining Chinese manuscripts were taken to Beijing in 1910 and are now in the National Library of China.

[...] Pelliot did, of course, after his return from Tun-huang, get in touch with Chinese scholars; but he had inherited so much of the nineteenth-century attitude about the right of Europeans to carry off ‘finds’ made in non-European lands that, like Stein, he seems never from the first to last to have had any qualms about the sacking of the Tun-huang library.”[15] While most studies use Dunhuang manuscripts to address issues in areas such as history and religious studies, some have addressed questions about the provenance and materiality of the manuscripts themselves.

Aurel Stein suggested that the manuscripts were "sacred waste", an explanation that found favour with later scholars including Fujieda Akira.

The variety of languages and scripts found among the Dunhuang manuscripts is a result of the multicultural nature of the region in the first millennium AD.

According to Akira Fujieda this was due to the lack of materials for constructing brushes in Dunhuang after the Tibetan occupation in the late 8th century.

[26] Several hundred manuscripts have been identified as notes taken by students,[27] including the popular Buddhist narratives known as bian wen (變文).