Timbuktu Manuscripts

[2] The manuscripts are written in Arabic and several African languages, in the Ajami script; this includes, but is not limited to, Fula, Songhay, Tamasheq, Bambara, and Soninke.

[3] The dates of the manuscripts range between the late 13th and the early 20th centuries (i.e., from the Islamisation of the Mali Empire until the decline of traditional education in French Sudan).

[5][6][7] Early scribes translated works of numerous well-known individuals (such as Plato, Hippocrates, and Avicenna) as well as reproduced a "twenty-eight volume Arabic language dictionary called The Mukham, written by an Andalusian scholar in the mid-eleventh century.

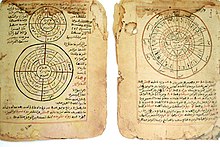

[8]: 25–26 Astronomers studied the movement of stars and relation to seasons, crafting charts of the heavens and precise diagrams of orbits of the other planets based on complex mathematical calculations; they even documented a meteor shower in 1593—"“In the year 991 in God’s month of Rajab the Godly, after half the night had passed stars flew around as if fire had been kindled in the whole sky—east, west, north and south...It became a nightly flame lighting up the earth, and people were extremely disturbed.

It continued until after dawn.”[8]: 26–27 Physicians documented instructions on nutrition and therapeutic properties of desert plants, and ethicists debated matters such as "polygamy, moneylending, and slavery.

"[8]: 27 "There were catalogues of spells and incantations; astrology; fortune-telling; black magic; necromancy, or communication with the dead by summoning their spirits to discover hidden knowledge; geomancy, or divining markings on the ground made from tossed rocks, dirt, or sand; hydromancy, reading the future from the ripples made from a stone cast into a pool of water; and other occult subjects..."[8]: 27 A volume titled Advising Men on Sexual Engagement with Their Women acted as a guide on aphrodasiacs and infertility remedies, as well as offering advice on "winning back" their wives.

[10] With the demise of Arabic education in Mali under French colonial rule, appreciation for the medieval manuscripts declined in Timbuktu, and many were being sold off.

[13] In 1998, Harvard University professor Henry Louis Gates visited Timbuktu for his PBS series Wonders of the African World.

Among the results of the project are: reviving the ancient art of bookbinding and training a solid number of local specialists; devising and setting up an electronic database to catalogue the manuscripts held at the Institut des Hautes Études et de Recherche Islamique – Ahmad Baba (IHERI-AB); digitizing a large number of manuscripts held at the IHERIAB; facilitating scholarly and technical exchange with manuscript experts in Morocco and other countries;[17] reviving IHERI-AB's journal Sankoré; and publishing the illustrated book, The Hidden Treasures of Timbuktu: Rediscovering Africa's Literary Culture.

It is implemented by the Lux-Development agency and the goals are: Since the events in the North of Mali in 2012, the project MLI/015 works with its main partners in Bamako on result 1.

[19] As well as preserving the manuscripts, the Cape Town project also aims to make access to public and private libraries around Timbuktu more widely available.

[5][6] U.S.-based book preservation expert Stephanie Diakité and Dr. Abdel Kader Haidara,[31] curator of one of the most important libraries of Timbuktu, a position handed down in his family for generations, organized the evacuation of the manuscripts to Bamako in the south of Mali.

[34] Abdel Kader thanked SAVAMA-DCI and their partners in a letter for enabling the evacuation of the manuscripts to the cities in the south of the country and supporting their storage.

[39] The French/German cultural TV channel ARTE produced a feature-length film about Timbuktu's manuscript heritage in 2009 entitled "Tombouctou: les manuscrits sauvés des sables" or "Timbuktus verschollenes Erbe: vom Sande verweht".

The book, The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu by Joshua Hammer,[8] provides vivid details about the collection of the manuscripts into libraries and subsequent efforts to remove them to safety during the dangerous conflict, in which the Islamist jihadis threatened to destroy them.