Herd immunity

[2][3][4] Once the herd immunity has been reached, disease gradually disappears from a population and may result in eradication or permanent reduction of infections to zero if achieved worldwide.

[7][14] In the same manner, children receiving vaccines against pneumococcus reduces pneumococcal disease incidence among younger, unvaccinated siblings.

[30][31] Alternatively, the reassortment of separate viral genome segments, or antigenic shift, which is more common when there are more strains in circulation, can also produce new serotypes.

[26][32] When either of these occur, memory T cells no longer recognize the virus, so people are not immune to the dominant circulating strain.

[30][32] As this evolution poses a challenge to herd immunity, broadly neutralizing antibodies and "universal" vaccines that can provide protection beyond a specific serotype are in development.

[18] The possibility of future shifting remains, so further strategies to deal with this include expansion of VT coverage and the development of vaccines that use either killed whole-cells, which have more surface antigens, or proteins present in multiple serotypes.

[18][36] If herd immunity has been established and maintained in a population for a sufficient time, the disease is inevitably eliminated – no more endemic transmissions occur.

[5] If elimination is achieved worldwide and the number of cases is permanently reduced to zero, then a disease can be declared eradicated.

[6] Eradication can thus be considered the final effect or end-result of public health initiatives to control the spread of contagious disease.

[6][7] In cases in which herd immunity is compromised, on the contrary, disease outbreaks among the unvaccinated population are likely to occur.

[2][7][38] Eradication efforts that rely on herd immunity are currently underway for poliomyelitis, though civil unrest and distrust of modern medicine have made this difficult.

[44] As the number of free riders in a population increases, outbreaks of preventable diseases become more common and more severe due to loss of herd immunity.

[2] The critical value, or threshold, in a given population, is the point where the disease reaches an endemic steady state, which means that the infection level is neither growing nor declining exponentially.

[54] In heterogeneous populations, R0 is considered to be a measure of the number of cases generated by a "typical" contagious person, which depends on how individuals within a network interact with each other.

[22] Vaccines usually have at least one contraindication for a specific population for medical reasons, but if both effectiveness and coverage are high enough then herd immunity can protect these individuals.

[5][83][92] For diseases that are especially severe among fetuses and newborns, such as influenza and tetanus, pregnant women may be immunized in order to transfer antibodies to the child.

[95][96] Therefore, herd immunity's inclusion in cost–benefit analyses results both in more favorable cost-effectiveness or cost–benefit ratios, and an increase in the number of disease cases averted by vaccination.

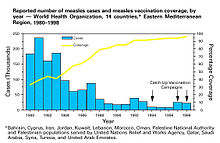

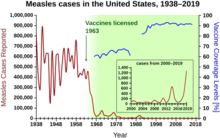

[97] From these, it can be observed that disease incidence may decrease to a level beyond what can be predicted from direct protection alone, indicating that herd immunity contributed to the reduction.

[98] Mass vaccination to induce herd immunity has since become common and proved successful in preventing the spread of many contagious diseases.

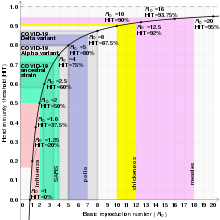

[45][46][47] The exact herd immunity threshold (HIT) varies depending on the basic reproduction number of the disease.

In 1916 veterinary scientists inside the same Bureau of Animal Industry used the term to refer to the immunity arising following recovery in cattle infected with brucellosis, also known as "contagious abortion."

By the end of the 1920s the concept was used extensively - particularly among British scientists - to describe the build up of immunity in populations to diseases such as diphtheria, scarlet fever, and influenza.

[2][80] Modeling of the spread of contagious disease originally made a number of assumptions, namely that entire populations are susceptible and well-mixed, which is not the case in reality, so more precise equations have been developed.