CRISPR

CRISPR (/ˈkrɪspər/) (an acronym for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) is a family of DNA sequences found in the genomes of prokaryotic organisms such as bacteria and archaea.

Hence these sequences play a key role in the antiviral (i.e. anti-phage) defense system of prokaryotes and provide a form of heritable,[3] acquired immunity.

[9][10] This editing process has a wide variety of applications including basic biological research, development of biotechnological products, and treatment of diseases.

[11][12] The development of the CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technique was recognized by the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020 awarded to Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna.

They accidentally cloned part of a CRISPR sequence together with the "iap" gene (isozyme conversion of alkaline phosphatase) from their target genome, that of Escherichia coli.

They recognized the diversity of the sequences that intervened in the direct repeats among different strains of M. tuberculosis[17] and used this property to design a typing method called spoligotyping, still in use today.

[19][20] By 2000, Mojica and his students, after an automated search of published genomes, identified interrupted repeats in 20 species of microbes as belonging to the same family.

[20][23] In 2002, Tang, et al. showed evidence that CRISPR repeat regions from the genome of Archaeoglobus fulgidus were transcribed into long RNA molecules subsequently processed into unit-length small RNAs, plus some longer forms of 2, 3, or more spacer-repeat units.

[27] A major advance in understanding CRISPR came with Jansen's observation that the prokaryote repeat cluster was accompanied by four homologous genes that make up CRISPR-associated systems, cas 1–4.

The Cas proteins showed helicase and nuclease motifs, suggesting a role in the dynamic structure of the CRISPR loci.

Koonin and colleagues extended this RNA interference hypothesis by proposing mechanisms of action for the different CRISPR-Cas subtypes according to the predicted function of their proteins.

That year Marraffini and Sontheimer confirmed that a CRISPR sequence of S. epidermidis targeted DNA and not RNA to prevent conjugation.

[44] Another collaboration comprising Virginijus Šikšnys, Gasiūnas, Barrangou, and Horvath showed that Cas9 from the S. thermophilus CRISPR system can also be reprogrammed to target a site of their choosing by changing the sequence of its crRNA.

[19] Groups led by Feng Zhang and George Church simultaneously published descriptions of genome editing in human cell cultures using CRISPR-Cas9 for the first time.

[12][45][46] It has since been used in a wide range of organisms, including baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae),[47][48][49] the opportunistic pathogen Candida albicans,[50][51] zebrafish (Danio rerio),[52] fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster),[53][54] ants (Harpegnathos saltator[55] and Ooceraea biroi[56]), mosquitoes (Aedes aegypti[57]), nematodes (Caenorhabditis elegans),[58] plants,[59] mice (Mus musculus domesticus),[60][61] monkeys[62] and human embryos.

[64] The CRISPR-Cas9 system has been shown to make effective gene edits in Human tripronuclear zygotes, as first described in a 2015 paper by Chinese scientists P. Liang and Y. Xu.

The scientists showed that during DNA recombination of the cleaved strand, the homologous endogenous sequence HBD competes with the exogenous donor template.

[67][68] Its original name, from a TIGRFAMs protein family definition built in 2012, reflects the prevalence of its CRISPR-Cas subtype in the Prevotella and Francisella lineages.

Using a small portion of N gene sequence from SARS-CoV-2 as a target in characterization of mCas13, revealed the sensitivity and specificity of mCas13 coupled with RT-LAMP for detection of SARS-CoV-2 in both synthetic and clinical samples over other available standard tests like RT-qPCR (1 copy/μL).

[104] CRISPR-Cas prevents bacteriophage infection, conjugation and natural transformation by degrading foreign nucleic acids that enter the cell.

[39] When a microbe is invaded by a bacteriophage, the first stage of the immune response is to capture phage DNA and insert it into a CRISPR locus in the form of a spacer.

Mutation studies confirmed this hypothesis, showing that removal of Cas1 or Cas2 stopped spacer acquisition, without affecting CRISPR immune response.

[121] IHF also enhances integration efficiency in the type I-F system of Pectobacterium atrosepticum,[122] but in other systems, different host factors may be required[123] Bioinformatic analysis of regions of phage genomes that were excised as spacers (termed protospacers) revealed that they were not randomly selected but instead were found adjacent to short (3–5 bp) DNA sequences termed protospacer adjacent motifs (PAM).

Functional type II systems encode an extra small RNA that is complementary to the repeat sequence, known as a trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA).

In type I systems correct base pairing between the crRNA and the protospacer signals a conformational change in Cascade that recruits Cas3 for DNA degradation.

[156] The spacer regions of CRISPR-Cas systems are taken directly from foreign mobile genetic elements and thus their long-term evolution is hard to trace.

[157] The non-random evolution of these spacer regions has been found to be highly dependent on the environment and the particular foreign mobile genetic elements it contains.

This characteristic makes CRISPRs easily identifiable in long sequences of DNA, since the number of repeats decreases the likelihood of a false positive match.

[124][133][168][169][170][171] However, this approach yields information only for specifically targeted CRISPRs and for organisms with sufficient representation in public databases to design reliable polymerase PCR primers.

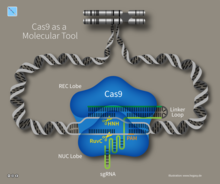

Gene editing with CRISPR-Cas9 involves a Cas9 nuclease and an engineered guide RNA, which come together to allow for the precise "cutting" of one or both strands of DNA at specific locations within the genome.

(1) Acquisition begins by recognition of invading DNA by Cas1 and Cas2 and cleavage of a protospacer.

(2) The protospacer is ligated to the direct repeat adjacent to the leader sequence and

(3) single strand extension repairs the CRISPR and duplicates the direct repeat. The crRNA processing and interference stages occur differently in each of the three major CRISPR systems.

(4) The primary CRISPR transcript is cleaved by cas genes to produce crRNAs.

(5) In type I systems Cas6e/Cas6f cleave at the junction of ssRNA and dsRNA formed by hairpin loops in the direct repeat. Type II systems use a trans-activating (tracr) RNA to form dsRNA, which is cleaved by Cas9 and RNaseIII. Type III systems use a Cas6 homolog that does not require hairpin loops in the direct repeat for cleavage.

(6) In type II and type III systems secondary trimming is performed at either the 5' or 3' end to produce mature crRNAs.

(7) Mature crRNAs associate with Cas proteins to form interference complexes.

(8) In type I and type II systems, interactions between the protein and PAM sequence are required for degradation of invading DNA. Type III systems do not require a PAM for successful degradation and in type III-A systems basepairing occurs between the crRNA and mRNA rather than the DNA, targeted by type III-B systems.