Hermann Detzner

For four years, Detzner and his troops provocatively marched through the bush, singing "Watch on the Rhine" and flying the German Imperial flag.

He led at least one expedition from the Huon Peninsula to the north coast, and a second by a mountain route, to attempt an escape to the neutral Dutch colony to the west.

After finding out that the war had ended, Detzner surrendered in full dress uniform, flying the Imperial flag, to Australian forces in January 1919.

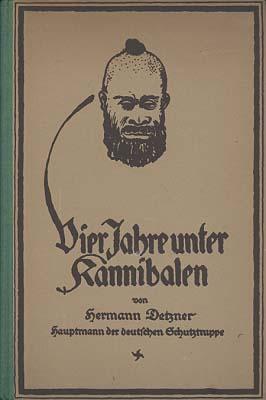

He wrote a book about his adventures – Four Years Among the Cannibals in the Interior of German New Guinea under the Imperial Flag, from 1914 until the Armistice – that sold well in Great Britain and Germany, entered three printings, and was translated into French, English, Finnish and Swedish.

[2] Hermann Detzner was trained as a topographer, surveyor, and an engineer, and received his promotion to Fahnrich in the 6 Infantry Regiment (Prussian), 2nd Pioneer Battalion, in February 1902.

[9] Detzner had had experience in joint operations in Kamerun in 1907–08 and could be expected to understand the challenges faced by the previous commission; he had a reputation as a methodical and precise engineer.

[13] On 11 November 1914, one of the carriers, left with several others to rest at a temporary camp, arrived bearing a note from Frederick Chisholm, an Australian Patrol Officer, informing him of the state of war between Germany and Great Britain and asking him to surrender at Nepa on the Lakekamu River, five days walk away.

[21] Eventually, Detzner found his way to the vicinity of a Lutheran mission at the Sattelberg, at a foggy, cool area at 800 meters (2,625 ft), above Finschhafen.

These were rugged and remote locations, accessible to Detzner, who had the help of native guides, but which the Australians, who usually travelled in larger patrols, could not penetrate.

[32] On 11 November 1918, Detzner received the news of the official end of the war with the German defeat from a worker at the Sattelberg Mission Station, he wrote a letter to the Australian commander in Morobe in which he offered his capitulation.

On 5 January 1919, he surrendered at the Finschhafen District headquarters, marching with his remaining German troops in a column, and wearing his carefully preserved full-dress uniform.

He was brought to Rabaul, the Australian headquarters,[33] and on 8 February 1919, was transferred to Sydney aboard the Melusia; after a brief internment in the prisoner of war camp at Holsworthy,[34] he was repatriated to Germany.

[41] In the 1920s, in addition to several articles and two maps of New Guinea, Detzner published a memoir of his adventures in the Niger valley—In the land of the Dju-Dju: travel experiences in the eastern watershed of the Niger—in 1923, but it did not achieve the popularity of his previous work.

[42] Detzner's book was wildly popular among the general population for its incredible tales of stubborn patriotism and its narratives describing the exotic locales of the lost imperial colonies.

His descriptions touched a chord in the German imagination: one of their own had explored the colony, walked its paths, seen its mountains and valleys, and met its people.

They were stocky, powerfully built, and long–limbed; they wore their hair in knots on the centre of their heads, which were otherwise shaven, and painted yellow and black lines across their chests.

As he pushed west to Mount Joseph, Detzner claimed, he had found the southern hills of the central watershed cut by numerous rivers flowing north to south.

[50] The writer attributed Detzner's success at staying ahead of the Australians to the perfidy of the German missionaries, who had agreed to remain neutral and in return for such agreement were allowed to continue their mission work.

Detzner was a civilian [emphasis in the original] surveyor, the writer claimed, not a soldier and he survived on mission station rations supplied by public subscription from the German plantation owners.

Two of the German missionaries in the Finschhafen District, Christian Keyser (also spelled Kayser or Keysser) and Otto Thiele, claimed Detzner had not spent the war roaming the jungle, one step ahead of the Australians, but had been under the Mission's protection the entire time.

In 1913, Keyser climbed the 4,121-meter (13,520 ft) Saruwaged Massif; over the course of his 21 years in New Guinea, he had identified hundreds of new plant and animal species, and had maintained a regular correspondence with the German Geographical Society in Berlin.

In Germany, during a meeting with Keyser, they discussed Detzner's claims, and Mayr lost no time in broadcasting the discrepancy to his scientific contacts in Europe and the United States.

[57] This was true, the Australians did find a box of Detzner's equipment in the location where the missionary Johann Flierl's oldest son, Wilhelm, had kept (or stored) his small canoe.

[58] Some of Detzner's assertions could be sustained through observable physical evidence: he had reportedly wasted to a mere 40 kilograms (88 lb) while roaming in the bush, which should not have happened, some supporters claimed, if he had indeed been under the protection of Keyser and Thiele.

[59] Despite his explanations, the missionaries Thiele and Keyser, whose own autobiography appeared in 1929,[60] and the widely respected Mayr, who by this time had become the leader of the Whitney South Seas Expeditions, continued to challenge the bulk of Detzner's scientific "discoveries".

In 1932, he admitted that he had mixed fact and fiction in his book, explaining that he had never intended it to be taken as science, but rather at its face-value, as the story of his adventurous years in the jungles of New Guinea.

The book in question is a scientific report in part only; it is primarily a fictional account of my experiences in New Guinea and owes its origin to the unusual circumstances prevailing in Germany at the time of my return.

[citation needed] The ambiguous wording of Detzner's resignation from the Geographical Society of Berlin—the use of such phrases as contains misrepresentations, scientific report in part only, primarily fictional, unusual circumstances in Germany, and so on—misled later scholars, many of whom remained unaware of the controversy surrounding his book.

[65] Consequently, his work continued to inform the geographical, linguistic, and anthropological investigations of New Guinean culture and geography well into the 1950s and 1960s,[66] much to the dismay of Ernst Mayr, who had been instrumental in discrediting Detzner in the 1920s.

No doubt the Australians could have made a more broadly organized attempt to capture him, and probably would have succeeded, but they did not make the effort; they preferred instead the more convenient "shoot-at-sight" method.