Herod the Great

He was the second son of Antipater the Idumaean, a high-ranking official under ethnarch Hyrcanus II, and Cypros, a Nabatean Arab princess from Petra, in present-day Jordan.

[13][14][15][16] Strabo, a contemporary of Herod, held that the Idumaeans, whom he identified as of Nabataean origin, constituted the majority of the population of western Judea, where they commingled with the Judaeans and adopted their customs.

[23] Herod rose to power largely through his father's good relations with the Roman general and dictator Julius Caesar, who entrusted Antipater with the public affairs of Judea.

The first threat came from his mother-in-law Alexandra, who sought to regain power for her family, the Hasmoneans,[40] whose dynasty Herod had overthrown in 37 BCE (see Siege of Jerusalem).

[48] While the term Doryphnoroi does not have an ethnic connotation, the unit was probably composed of distinguished veteran soldiers and young men from the most influential Jewish families.

[48] Thracians had served in the Jewish armies since the Hasmonean dynasty, while the Celtic contingent were former bodyguards of Cleopatra given as a gift by Augustus to Herod following the Battle of Actium.

Although he built fortresses (Masada, Herodium, Alexandrium, Hyrcania, and Machaerus) in which he and his family could take refuge in case of insurrection, these vast projects were also intended to gain the support of the Jews and improve his reputation as a leader.

In Jerusalem, Herod introduced foreign forms of entertainment, and erected a golden eagle at the entrance of the Temple,[52] which suggested a greater interest in the welfare of Rome than of Jews.

Heavy outbreaks of violence and riots followed Herod's death in many cities, including Jerusalem, as pent-up resentments boiled over.

[49] The relationship between Herod and Augustus demonstrates the fragile politics of a deified Emperor and a King who ruled over the Jewish people and their holy lands.

[44] Recent findings suggest that the Temple Mount walls and Robinson's Arch may not have been completed until at least 20 years after his death, during the reign of Herod Agrippa II.

Herod's other achievements include the development of water supplies for Jerusalem, building fortresses such as Masada and Herodium, and founding new cities such as Caesarea Maritima and the enclosures of Cave of the Patriarchs and Mamre in Hebron.

Herod assembled the chief priests and scribes of the people and asked them where the "Anointed One" (the Messiah, Greek: Ὁ Χριστός, romanized: ho Christos) was to be born.

[58] Contemporary non-biblical sources, including Josephus and the surviving writings of Nicolaus of Damascus (who knew Herod personally), provide no corroboration for Matthew's account of the massacre,[59] and it is not mentioned in the Gospel of Luke.

[63] Others, such as Paul Maier, suggest that since Bethlehem was a smaller town, the slaughter of about a half dozen children would not have warranted a mention from Josephus.

[85] In Josephus' account, Herod's death was preceded by first a Jewish fast day (10 Tevet 3761/Sun 24 Dec 1 BCE), a lunar eclipse and followed by Passover (27 March 1 CE).

[86] Objections to the 4 BCE date include the assertion that there was not nearly enough time between the eclipse on March 13 and Passover on April 10 for the recorded events surrounding Herod's death to have taken place.

[84][87][73] In 66 CE, Eleazar ben Hanania compiled the Megillat Taanit, which contains two unattributed entries for cause of festivity: 7 Kislev and 2 Shevat.

A later Scholion (commentary) on the Megillat Taanit attributes the 7 Kislev festivity to king Herod the Great's death (no year is mentioned).

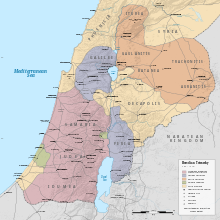

[89] Augustus recognised Herod's son Herod Archelaus as ethnarch of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea from c. 4 BCE – c. 6 CE Augustus then judged Archelaus incompetent to rule, removed him from power, and combined the provinces of Samaria, Judea proper, and Idumea into Iudaea province.

The location of Herod's tomb is documented by Josephus, who writes, "And the body was carried two hundred furlongs, to Herodium, where he had given order to be buried.

"[94] Professor Ehud Netzer, an archaeologist from the Hebrew University, read the writings of Josephus and focused his search on the vicinity of the pool and its surroundings.

An article in the New York Times states, Lower Herodium consists of the remains of a large palace, a race track, service quarters, and a monumental building whose function is still a mystery.

Not all scholars agree with Netzer: in an article for the Palestine Exploration Quarterly, archaeologist David Jacobson (University of Oxford) wrote that "these finds are not conclusive on their own and they also raise new questions.

[102] The Israel Nature and Parks Authority and the Gush Etzion Regional Council intend to recreate the tomb out of a light plastic material, a proposal that has received strong criticism from major Israeli archeologists.

Modern critics have described him as "the evil genius of the Judean nation",[105] and as one who would be "prepared to commit any crime in order to gratify his unbounded ambition.

Although Herod considered himself king of the Jews, he let it be known that he also represented the non-Jews living in Judea, building temples for other religions outside of the Jewish areas of his kingdom.

For instance, he minted coins without human images to be used in Jewish areas and acknowledged the sanctity of the Second Temple by employing priests as artisans in its construction.

[111] While it has been proven that Herod showed a great amount of disrespect toward the Jewish religion, scholar Eyal Regev suggests that the presence of these ritual baths shows that Herod found ritual purity important enough in his private life to place a large number of these baths in his palaces despite his several connections to gentiles and pagan cults.

[112] However, he was also praised for his work, being considered the greatest builder in Jewish history,[citation needed] and one who "knew his place and followed [the] rules".

Territory under Herod Archelaus

Territory under Herod Antipas

Territory under Philip the Tetrarch

Territory under Salome I