Histories (Herodotus)

Herodotus portrays the conflict as one between the forces of slavery (the Persians) on the one hand, and freedom (the Athenians and the confederacy of Greek city-states which united against the invaders) on the other.

[12] In particular, it is possible that he copied descriptions of the crocodile, hippopotamus, and phoenix from Hecataeus's Circumnavigation of the Known World (Periegesis / Periodos ges), even misrepresenting the source as "Heliopolitans" (Histories 2.73).

[14] There is no proof that Herodotus derived the ambitious scope of his own work, with its grand theme of civilizations in conflict, from any predecessor, despite much scholarly speculation about this in modern times.

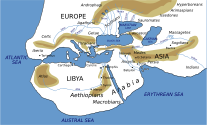

For example, he argues for continental asymmetry as opposed to the older theory of a perfectly circular earth with Europe and Asia/Africa equal in size (Histories 4.36 and 4.42).

[16] His debt to previous authors of prose "histories" might be questionable, but there is no doubt that Herodotus owed much to the example and inspiration of poets and story-tellers.

He lays this out in the preamble: "This is the publication of the research of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, so that the actions of people shall not fade with time, so that the great and admirable achievements of both Greeks and barbarians shall not go unrenowned, and, among other things, to set forth the reasons why they waged war on each other.

"[24] Some readers of Herodotus believe that his habit of tying events back to personal motives signifies an inability to see broader and more abstract reasons for action.

[27] Some authors, including Geoffrey de Ste-Croix and Mabel Lang, have argued that Fate, or the belief that "this is how it had to be," is Herodotus's ultimate understanding of causality.

[29] John Gould argues that Herodotus should be understood as falling in a long line of story-tellers, rather than thinking of his means of explanation as a "philosophy of history" or "simple causality."

Persian and Egyptian informants tell stories that dovetail neatly into Greek myths and literature, yet show no signs of knowing their own traditions.

[41] Like many ancient historians, Herodotus preferred an element of show[d] to purely analytic history, aiming to give pleasure with "exciting events, great dramas, bizarre exotica.

[54][55] So even if the Histories were criticized in some regards since antiquity, modern historians and philosophers generally take a more positive view as to their source and epistemologic value.

"[48] German historian Detlev Fehling questions whether Herodotus ever traveled up the Nile River, and considers doubtful almost everything that he says about Egypt and Ethiopia.

[57][51] Fehling states that "there is not the slightest bit of history behind the whole story" about the claim of Herodotus that Pharaoh Sesostris campaigned in Europe, and that he left a colony in Colchia.

[49][42] However, a recent discovery of a baris (described in The Histories) during an excavation of the sunken Egyptian port city of Thonis-Heracleion lends credence to Herodotus's travels and storytelling.

A. H. L. Heeren quoted Herodotus throughout his work and provided corroboration by scholars regarding several passages (source of the Nile, location of Meroë, etc.).

[59] Cheikh Anta Diop provides several examples (like the inundations of the Nile) which, he argues, support his view that Herodotus was "quite scrupulous, objective, scientific for his time."

He also passes on reports from Phoenician sailors that, while circumnavigating Africa, they "saw the sun on the right side while sailing westwards", although, being unaware of the existence of the southern hemisphere, he says that he does not believe the claim.

[66][67][68] After journeys to India and Pakistan, French ethnologist Michel Peissel claimed to have discovered an animal species that may illuminate one of the most bizarre passages in the Histories.

[69] In Book 3, passages 102 to 105, Herodotus reports that a species of fox-sized, furry "ants" lives in one of the far eastern, Indian provinces of the Persian Empire.

According to Peissel, he interviewed the Minaro tribal people who live in the Deosai Plateau, and they have confirmed that they have, for generations, been collecting the gold dust that the marmots bring to the surface when they are digging their burrows.

[71] Similarly, in a Corinthian Oration, Dio Chrysostom (or yet another pseudonymous author) accused the historian of prejudice against Corinth, sourcing it in personal bitterness over financial disappointments[72] – an account also given by Marcellinus in his Life of Thucydides.

K. H. Waters relates that "Herodotos did not work from a purely Hellenic standpoint; he was accused by the patriotic but somewhat imperceptive Plutarch of being philobarbaros, a pro-barbarian or pro-foreigner.

"[80] Although Herodotus considered his "inquiries" a serious pursuit of knowledge, he was not above relating entertaining tales derived from the collective body of myth, but he did so judiciously with regard for his historical method, by corroborating the stories through enquiry and testing their probability.

In Book One, passages 23 and 24, Herodotus relates the story of Arion, the renowned harp player, "second to no man living at that time," who was saved by a dolphin.

Herodotus prefaces the story by noting that "a very wonderful thing is said to have happened," and alleges its veracity by adding that the "Corinthians and the Lesbians agree in their account of the matter."

Arion discovered the plot and begged for his life, but the crew gave him two options: that either he kill himself on the spot or jump ship and fend for himself in the sea.

John Herington has developed a helpful metaphor for describing Herodotus's dynamic position in the history of Western art and thought – Herodotus as centaur: The human forepart of the animal ... is the urbane and responsible classical historian; the body indissolubly united to it is something out of the faraway mountains, out of an older, freer and wilder realm where our conventions have no force.

As James Romm has written, Herodotus worked under a common ancient Greek cultural assumption that the way events are remembered and retold (e.g. in myths or legends) produces a valid kind of understanding, even when this retelling is not entirely factual.

He traveled the eastern Mediterranean and beyond to do research into human affairs: from Greece to Persia, from the sands of Egypt to the Scythian steppes, and from the rivers of Lydia to the dry hills of Sparta.