Hesychast controversy

The dispute concluded with the victory of the Palamists and the inclusion of Palamite doctrine as part of the dogma of the Eastern Orthodox Church as well as the canonization of Palamas.

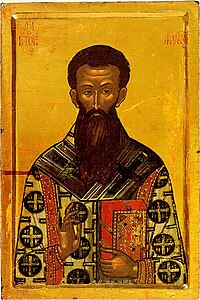

Reacting to criticisms of his theological writings that Gregory Palamas, an Athonite monk and exponent of hesychasm, had courteously communicated to him, Barlaam encountered Hesychasts and heard descriptions of their practices.

However, in 1351, at a synod under the presidency of Emperor John VI Kantakouzenos, Palamas' real Essence-Energies distinction was established as the doctrine of the Orthodox Church.

[4][5][6] In the early 14th century, Gregory Sinaita learned from Arsenius of Crete the form of hesychasm that is "a particular psychosomatic technique in combination with the Jesus Prayer"[3] and spread the doctrine, bringing it to the monks on Mount Athos.

[7] Scholars such as Christopher Livanos and Martin Jugie have argued that there are many widely held generalizations and stereotypes that are only partly true and often only applicable to certain individuals and specific periods during the controversy.

Livanos asserts that "considering Byzantine, rather than modern Orthodox, polemics it is quite rare for a Greek writer to criticize the Latins for using logic in theology."

"[8] Martin Jugie suggests that many scholars have imprudently indulged in quick generalizations, panoramic overviews and systematic constructions when discussing the Hesychast controversy.

Hankins argues that, "the original debate between Barlaam and Palamas was not a matter of Aristotelianism versus Platonism, but rather grew from a methodological dispute about the best way to defend Orthodoxy against the attacks of the Western controversialists."

[12] Similarly, John Meyendorff asserts that the "widespread view that Eastern Christian thought is Platonic, in contrast to Western Aristotelianism" is erroneous.

Meyendorff posits that the target of Byzantine monks in general and Palamas in particular was actually "secular philosophy" and so-called "Hellenic wisdom".

In stark contrast to this Hellenic culture, Byzantine monastic thought continually emphasized that theirs was a "faith preached by a Jewish Messiah" and that their destiny was to become a "new Jerusalem".

"[15] According to Meyendorff, this confrontation between Barlaam's nominalism and Palamas' realism began with a dispute over the best way to address the Filioque controversy with the Latins but quickly spilled over into a conflict over Hesychasm.

[17] Meyendorff characterized the Hesychast controversy as a conflict between the Byzantine intellectuals (lovers of secular "Hellenic" learning) and the Palamites (upholders of the mystical monastic tradition).

However, Meyendorff asserts that it is precisely in the thirteenth century that "an institutional, social and conceptual bifurcation establishes itself between the Latin West and the Greek (and Slavic) East.

During the fourteenth century, Byzantine Emperors appealed to the west for help on a number of occasions; however, the Pope would only consider sending aid in return for a reunion of the Eastern Orthodox Church with the See of Rome.

Around 1336, Gregory Palamas received copies of treatises written by Barlaam against the Latins, condemning their insertion of the Filioque into the Nicene Creed.

He had shown that, in the hands of monks who were inadequately instructed and ignorant of the true Hesychast teaching, the psycho-physical precepts of Hesychasm could produce "dangerous and ridiculous results".

[30] Barlaam viewed this doctrine of "uncreated light" to be polytheistic because it postulated two eternal substances, a visible and an invisible God.

[32] This time, Barlaam derisively called the Hesychasts, omphalopsychoi (men with their souls in their navels) and accused them of the heresy of Messalianism, also known as Bogomilism in the East.

Although several significant exceptions leave the issue open to question, in the popular mind (and traditional historiography), the supporters of "Palamism" and of "Kantakouzenism" are usually equated.

While Kantakouzenos sought to reach an understanding with Rome and Demetrios Cydones ultimately joined the Latin Church, Gregoras remained vehemently Latinophobe.

Martin Jugie attributes this to the fact that, by this time, the patriarchs of Constantinople and the overwhelming majority of the clergy and laity had come to view the cause of Hesychasm as one and the same with that of Orthodoxy.

Although Barlaam initially hoped for a second chance to present his case against Palamas, he soon realised the futility of pursuing his cause, and left for Calabria where he converted to the Latin Church and was appointed Bishop of Gerace.

[9] Palamas was arrested in the autumn of 1342 at Heraclea, where he had taken refuge, and shortly thereafter he was imprisoned in the monastery of the Incomprehensible where he remained until Kantakouzenos triumphantly entered Constantinople in 1347.

After a heated debate, it was agreed that Palamas would appear before the council in the position of the accused, and that Gregoras and his followers would have full liberty to present their grievances against him.

[21] Nicephorus Gregoras refused to submit to the dictates of the synod and was effectively imprisoned in a monastery until the Palaeologi triumphed in 1354 and deposed Kantakouzenos.

After the triumph of the Palæologi, the Barlaamite faction convened an anti-Hesychast synod at Ephesus but, by this time, the patriarchs of Constantinople and the overwhelming majority of the clergy and laity had come to view the cause of Hesychasm as one and the same with that of Orthodoxy.

Throughout the second half of the fourteenth century, there are numerous reports of Christians returning from the "Barlaamite heresy" to Palamite orthodoxy, suggesting that the process of imposing universal acceptance of Palamism spanned several decades.

[47] Despite the initial opposition of the anti-Palamites and some patriarchates and sees, the resistance dwindled away over time and ultimately Palamist doctrine became accepted throughout the Eastern Orthodox Church.

[40] For theologians who remained in opposition, there was ultimately no choice but to emigrate and convert to the Latin church, a path taken by Kalekas as well as Demetrios Kydones and John Kyparissiotes.