Heterothallism

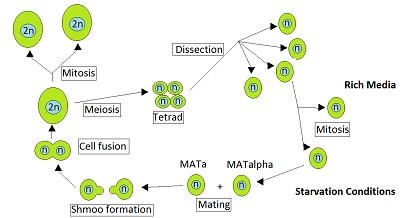

During vegetative growth that ordinarily occurs when nutrients are abundant, S. cerevisiae reproduces by mitosis as either haploid or diploid cells.

Katz Ezov et al.[4] presented evidence that in natural S. cerevisiae populations clonal reproduction and a type of “self-fertilization” (in the form of intratetrad mating) predominate.

Ruderfer et al.[3] analyzed the ancestry of natural S. cerevisiae strains and concluded that outcrossing occurs only about once every 50,000 cell divisions.

[citation needed] Rather, a short-term benefit, such as meiotic recombinational repair of DNA damages caused by stressful conditions such as starvation may be the key to the maintenance of sex in S.

A. fumigatus, is widespread in nature, and is typically found in soil and decaying organic matter, such as compost heaps, where it plays an essential role in carbon and nitrogen recycling.

Colonies of the fungus produce from conidiophores thousands of minute grey-green conidia (2–3 μm) that readily become airborne.

A. fumigatus possesses a fully functional sexual reproductive cycle that leads to the production of cleistothecia and ascospores.

In 2009, a sexual state of this heterothallic fungus was found to arise when strains of opposite mating type were cultured together under appropriate conditions.

[10] Sexuality generates diversity in the aflatoxin gene cluster in A. flavus,[11] suggesting that production of genetic variation may contribute to the maintenance of heterothallism in this species.

Henk et al.[12] showed that the genes required for meiosis are present in T. marneffei, and that mating and genetic recombination occur in this species.

Protoperithecia are formed most readily in the laboratory when growth occurs on solid (agar) synthetic medium with a relatively low source of nitrogen.

The sexual cycle is initiated (i.e. fertilization occurs) when a cell (usually a conidium) of opposite mating type contacts a part of the trichogyne (see figure, top of §).

The products of these nuclear divisions (still in pairs of unlike mating type, i.e. ‘A’ / ‘a’) migrate into numerous ascogenous hyphae, which then begin to grow out of the ascogonium.

As the above events are occurring, the mycelial sheath that had enveloped the ascogonium develops as the wall of the perithecium, becomes impregnated with melanin, and blackens.

In a mature ascus containing 8 ascospores, pairs of adjacent spores are identical in genetic constitution, since the last division is mitotic, and since the ascospores are contained in the ascus sac that holds them in a definite order determined by the direction of nuclear segregations during meiosis.