Mating of yeast

Diploid cells can reproduce asexually, but under nutrient-limiting conditions, they undergo meiosis to produce new haploid spores.

The differences between a and α cells, driven by specific gene expression patterns regulated by the MAT locus, are crucial for the mating process.

Additionally, the decision to mate involves a highly sensitive and complex signaling pathway that includes pheromone detection and response mechanisms.

[4] Similarly, α cells produce α-factor, and respond to a-factor by growing a projection towards the source of the pheromone.

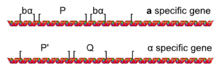

[9] The different sets of transcriptional repression and activation, which characterize a and α cells, are caused by the presence of one of two alleles for a mating-type locus called MAT: MATa or MATα located on chromosome III.

[7] The MATa allele of MAT encodes a gene called a1, which directs the a-specific transcriptional program (such as expressing STE2 and repressing STE3) that defines an a haploid cell.

The MATα allele of MAT encodes the α1 and α2 genes, which directs the α-specific transcriptional program (such as expressing STE3, repressing STE2, and producing prepro-α-factor) that defines an α haploid cell.

Haploid cells only contain one copy of each of the 16 chromosomes and therefore only possess one MAT allele (either MATa or MATα), which determines their mating type.

As a result, these diploid cells cannot form the a1-α2 protein complex needed to repress haploid-specific genes.

[40] This switch-like mechanism allows yeast cells to avoid making an unwise commitment to a highly demanding procedure.

[51] The vast majority of yeast strains studied in laboratories have been altered such that they cannot perform mating type switching (by deletion of the HO gene; see below).

[52] Haploid yeast switch mating type by replacing the information present at the MAT locus.

Thus, the silenced alleles of MATa and MATα present at HML and HMR serve as a source of genetic information to repair the HO-induced DNA damage at the active MAT locus.

[7] The repair of the MAT locus after cutting by the HO endonuclease almost always results in a mating type switch.

[6] This results in MAT being repaired to the MATα allele, switching the mating type of the cell from a to α.

[68] In 2006, evolutionary geneticist Leonid Kruglyak found that S. cerevisiae matings only involve out-crossing between different strains roughly once every 50,000 cell divisions.

[69] This suggests that yeast primarily maintain their capability to mate through recombinational DNA repair during meiosis, rather than natural selection for fitness among a population with high genetic variability.

[71] Exposure of S. pombe to hydrogen peroxide, which causes oxidative stress to DNA, strongly induces mating, meiosis, and formation of meiotic spores.

[6] Cryptococcus neoformans is a basidiomycetous fungus that grows as a budding yeast in culture and infected hosts.

It undergoes a filamentous transition during the sexual cycle to produce spores, the suspected infectious agent.

[74] The diploid nuclei of blastospores can then undergo meiosis, including recombination, to form haploid basidiospores that can then be dispersed.

[75] Meiosis in C. neoformans may be performed to promote DNA repair in DNA-damaging environments, such as host-mediated responses to infection.