High-nutrient, low-chlorophyll regions

Macronutrients (e.g., nitrate, phosphate, silicic acid) are generally available in higher quantities in surface ocean waters, and are the typical components of common garden fertilizers.

[1][2] The discovery of HNLC regions has fostered scientific debate about the ethics and efficacy of iron fertilization experiments which attempt to draw down atmospheric carbon dioxide by stimulating surface-level photosynthesis.

For photosynthesis to occur, macronutrients such as nitrate and phosphate must be available in sufficient ratios and bioavailable forms for biological utilization.

Modern satellite observations monitor and track global chlorophyll α abundances in the ocean via remote sensing.

[5] While HNLC broadly describes the biogeochemical trends of these large ocean regions, all three zones experience seasonal phytoplankton blooms in response to global atmospheric patterns.

For example, the selection of phytoplankton with a high surface area to volume ratio results in HNLC regions being dominated by nano- and picoplankton.

Common picoplankton within these regions include genera such as prochlorococcus (not generally found in the North Pacific), synechococcus, and various eukaryotes.

[6] The study concluded that surface waters of the eastern North Pacific are generally dominated by picoplankton despite the relative abundance of macronutrients.

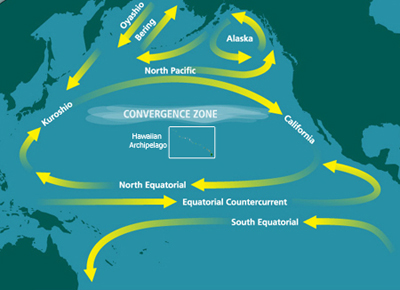

Ocean currents are driven by seasonal atmospheric patterns which transport iron from the Kuril-Kamchatka margin into the western Subarctic Pacific.

This introduction of iron provides a subsurface supply of micronutrients, which can be used by primary producers during upwelling of deeper waters to the surface.

[22] Volcanic ash from the eruption of the Kasatochi volcano in August 2008 provided an example of natural iron fertilization in the Northeast Pacific Ocean.

The Equatorial Pacific spans nearly half of Earth’s circumference and plays a major role in global marine new primary production.

Like other major HNLC provinces, the Equatorial Pacific is considered nutrient-limited due to lack of trace metals such as iron.

[27] During these glacial periods, the Equatorial Pacific increased its export of marine new production,[27] thus providing a sink of atmospheric carbon dioxide.

[14] Picoplankton are the most abundant marine primary producers in these regions due mainly to their ability to assimilate low concentrations of trace metals.

Therefore, iron inputs and primary production in the Southern Ocean are sensitive to iron-rich Saharan dust deposited over the Atlantic.

[4] Some regions of the Southern Ocean experience both adequate bioavailable iron and macronutrient concentrations yet phytoplankton growth is limited.

[40] Phytoplankton growth rate is very intense and short lived in open areas surrounded by sea ice and permanent sea-ice zones.

Unlike the open waters of the Southern Ocean, grazing along continental shelf margins is low, so most phytoplankton that are not consumed sink to the sea floor which provides nutrients to benthic organisms.

[39] Given the remote location of HNLC areas, scientists have combined modeling and observational data in order to study limits on primary production.

Two current explanations for global HNLC regions are growth limitations due to iron availability and phytoplankton grazing controls.

In 1988, John Martin confirmed the hypothesis that iron limits phytoplankton blooms and growth rates in the North Pacific.

in HNLC areas, large phytoplankton responses such as decreased surface nutrient concentration and increased biological activity were observed.

[48] Iron enters remote HNLC regions through two primary methods: upwelling of nutrient-rich water and atmospheric dust deposition.

Iron needs to be replenished frequently and in bioavailable forms because of its insolubility, rapid uptake through biological systems, and binding affinity with ligands.

[53] Due to the Southern Ocean's isolation from land, upwelling related to eddy diffusivity provides iron to HNLC regions.

[50][56] Current scientific consensus agrees that HNLC areas lack high productivity because of a combination of iron and physiological limitations, grazing pressure, and physical forcings.

[42][43] Even if carbon is exported to depth, raining organic matter can be respired, potentially creating mid-column anoxic zones or causing acidification of deep ocean water.

[61][64] Pronounced community shifts to diatoms have been observed during fertilization, and it's still unclear if the change in species composition has any long-term environmental effects.

The volume of bio-diesel and mass of bio-char would provide an accurate figure for producing (when sequestering) and selling (when removing from wells or mines) carbon credits.