High Middle Ages

The Magyars ceased their expansion in the 10th century, and by the year 1000, a Christian Kingdom of Hungary had become a recognized state in Central Europe that was forming alliances with regional powers.

In the 11th century, populations north of the Alps began a more intensive settlement, targeting "new" lands, some areas of which had reverted to wilderness after the end of the Western Roman Empire.

At the same time, settlers moved beyond the traditional boundaries of the Frankish Empire to new frontiers beyond the Elbe River, which tripled the size of Germany in the process.

The Christian kingdoms took much of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim control, and the Normans conquered southern Italy, all part of the major population increases and the resettlement patterns of the era.

[14] Despite population growth, agricultural output remained relatively rigid throughout the period; between the 10th and 13th centuries, migration southwards to exposed areas was incentivized by the possibility of enjoying privileges and acquiring properties.

[16] While Muslim lands enjoyed a certain demographic and financial edge[clarification needed], Almoravids and Almohads from northern Africa featured volatile state structures;[17] barring (unsuccessful) attempts to take Toledo, they did not stand out for carrying out an expansionist policy.

These were in particular the thalassocracies of Pisa, Amalfi, Genoa and Venice, which played a key role in European trade from then on, making these cities become major financial centers.

Meanwhile, Norway extended its Atlantic possessions, ranging from Greenland to the Isle of Man, while Sweden, under Birger Jarl, built up a power-base in the Baltic Sea.

By the time of the High Middle Ages, the Carolingian Empire had been divided and replaced by separate successor kingdoms called France and Germany, although not with their modern boundaries.

By the time of the High Middle Ages, the Carolingian Empire had been divided and replaced by separate successor kingdoms called France and Germany, although not with their modern boundaries.

Germany was under the banner of the Holy Roman Empire, which reached its high-water mark of unity and political power under Kaiser Frederick Barbarossa.

David's decisive victory in the Battle of Didgori (1121) against the Seljuk Turks, as a result of which Georgia recaptured its lost capital Tbilisi, marked the beginning of the Georgian Golden Age.

David's granddaughter Queen Tamar continued the upward rise, successfully neutralizing internal opposition and embarking on an energetic foreign policy aided by further decline of the hostile Seljuk Turks.

During the first half of this period (c. 1025—1185), Byzantine Empire dominated the Southeast Europe, and under the Komnenian emperors there was a revival of prosperity and urbanization; however, their domination of Southeast Europe was coming to an end with a successful Vlach-Bulgarian rebellion in 1185, and henceforth the region was divided between the Byzantines in Greece, some parts of Macedonia, and Thrace, the Bulgarians in Moesia and most of Thrace and Macedonia, and the Serbs to the northwest.

Farmers grew wheat well north into Scandinavia, and wine grapes in northern England, although the maximum expansion of vineyards appeared to occur within the Little Ice Age period.

Food production also increased during this time as new ways of farming were introduced, including the use of a heavier plow, horses instead of oxen, and a three-field system that allowed the cultivation of a greater variety of crops than the earlier two-field system—notably legumes, the growth of which prevented the depletion of important nitrogen from the soil.

They were conducted under papal authority, initially with the intent of reestablishing Christian rule in The Holy Land by taking the area from the Muslim Fatimid Caliphate.

The Knights Hospitaller were originally a Christian organization founded in Jerusalem in 1080 to provide care for poor, sick, or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land.

The Teutonic Knights were a German religious order formed in 1190, in the city of Acre, to aid Christian pilgrims on their way to the Holy Lands and to operate hospitals for the sick and injured in Outremer.

After Muslim forces captured the Holy Lands, the order moved to Transylvania in 1211 and later, after being expelled, invaded pagan Prussia with the intention of Christianizing the Baltic region.

The Teutonic Knights' power hold, which became considerable, was broken in 1410, at the Battle of Grunwald, where the Order suffered a devastating defeat against a joint Polish-Lithuanian army.

Prominent opponents of various aspects of the scholastic mainstream included Duns Scotus, William of Ockham, Peter Damian, Bernard of Clairvaux, and the Victorines.

Christian heresies existed in Europe before the 11th century but only in small numbers and of local character: in most cases, a rogue priest, or a village returning to pagan traditions.

Some Catholic monastic leaders, such as Francis of Assisi, the founder of the Franciscans, had to be recognized directly by the Pope so as not to be confused with actual heretical movements such as the Waldensians.

At the beginning of the 13th century there were reasonably accurate Latin translations of the main works of almost all the intellectually crucial ancient authors,[22] allowing a sound transfer of scientific ideas via both the universities and the monasteries.

By then, the natural science contained in these texts began to be extended by notable scholastics such as Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, Albertus Magnus and Duns Scotus.

Precursors of the modern scientific method can be seen already in Grosseteste's emphasis on mathematics as a way to understand nature, and in the empirical approach admired by Bacon, particularly in his Opus Majus.

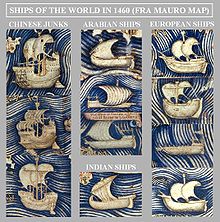

The period saw major technological advances, including the adoption or invention of windmills, watermills, printing (though not yet with movable type), gunpowder, the astrolabe, glasses, scissors of the modern shape, a better clock, and greatly improved ships.

His pupil and successor at the head of Philosophy at the University of Constantinople Ioannes Italos continued the Platonic line in Byzantine thought and was criticized by the Church for holding opinions it considered heretical, such as the doctrine of transmigration.

A larger number of plays survive from France and Germany in this period and some type of religious dramas were performed in nearly every European country in the Late Middle Ages.