Battle of Hill 70

The goals of the Canadian Corps were only partially accomplished; the Germans were prevented from transferring local divisions to the Ypres Salient but failed to draw in troops from other areas.

Horne already desired to cut off the salient containing Lens to shorten the front, while unwilling to risk a costly and slow frontal assault into the maze of ruins.

[4] On 7 May, Haig informed the British army commanders that the French had terminated the Nivelle Offensive and the strategy of returning to a war of manoeuvre.

Operations to exhaust the powers of resistance of the German armies would resume by systematic, surprise attacks and when this was complete, the British would begin an offensive at Ypres to capture the Belgian coast and reach the frontier with the Netherlands.

[4] On 8 May, Horne told the First Army corps commanders that The ruling principles in the conduct of these operations will be careful selection of important objectives of a limited nature, deliberate preparation of the attack, concentration of artillery and economy of infantry, combined in each case with feint attacks and smoke and gas on other positions of the front.On 7 July, Haig gave orders that the Canadian Corps was to capture Lens to stop the 6th Army from sending troops north to Flanders.

[10] In May and early June, First Army units conducted eighteen raids and minor actions, moving the front line slowly eastwards over the Douai Plain.

Horne doubted that the army had sufficient men and artillery for the task and arranged for the 46th (North Midland) Division, on the right of I Corps, to make preparations to take Hill 70 and the vicinity but only if reinforcements from GHQ were forthcoming.

The 4th Canadian Division on the left flank of the Canadian Corps south of the Souchez River (a tributary of the Deûle) and the 46th (North Midland) Division on the right of I Corps, north of the river, were to attack on a front of 4,800 yd (2.7 mi; 4.4 km) to eliminate a German salient from Avion to the west end of Lens and to occupy Hill 65 (Reservoir Hill).

Horne expected that the operations would take place in early July but found that many of the best heavy guns were to be sent to Flanders and brought forward the date to 28 June.

Gavrelle Mill and a new line was consolidated, despite the rainstorm, from which the areas to the north-east and east around Neuvireuil and Fresnes could be observed, along with Greenland Hill to the south-west.

The suggested alternative was not well received by Major-General (Warren) Hastings Anderson, the First Army chief of staff, because one purpose of the operation was to threaten Lille, which could only occur with the capture of Lens after the attack on Avion.

Rain and flooding from the Souchez stopped patrols from probing the German main line of resistance in the north-eastern part of Avion and along a railway embankment about 600 further on.

The position had three thick belts of barbed wire, a light railway for supply and eleven strongpoints with fields of fire into Commotion Trench, the final Canadian objective.

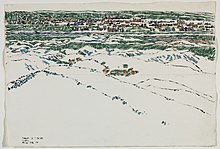

[24] Hill 70 overlooked Lens and the Douai plain and Currie believed that the Germans would commit troops that they could ill-afford to lose, to regain a position that they dared not leave in Canadian possession.

The 15th, 50th and 2nd Canadian Heavy Artillery Group bombarded German gun positions revealed by aerial photographs, flash spotting and sound ranging, neutralization being more effective than destruction.

High explosive, gas and shrapnel shells were to be fired at German gun positions revealed by RFC reconnaissance photographs and the flash-spotters and sound rangers, to kill gunners and supply horses.

An advanced landing ground at Petit Sains was made ready for 43 Squadron 1½ Strutters to mount continuous counter-attack reconnaissance patrols.

[36] In late July, the 9th Canadian Brigade feinted a direct attack of Lens by engaging units of the German 36th Reserve Division at Méricourt Trench.

At 4:26 a.m. Special Companies RE fired 400 drums of oil from Livens projectors, which dropped into the German defences in Cité St Élisabeth, creating a smoke-screen and began an hour-long smoke bombardment from 4-inch Stokes mortars.

On the right (southern) flank in the 4th Canadian Division area, a Special Company used Livens projectors to fire 200 gas cylinders into German positions around Avion.

On the southern (right) flank, the 4th Canadian Division diversion succeeded and with fewer guns in support, the German artillery reply was more effective than further north.

[52] The Germans stopped wave attacks and counter-attacked with dispersed groups of troops trickling forward using cover; some managed to reach the Canadian defences and fight hand-to-hand.

Many gunners became casualties after gas fogged the goggles of their respirators and they were forced to remove them to set fuses, lay their sights and maintain accurate fire.

Communication between the forward units and brigade headquarters had broken down at the beginning of the attack and could not be restored due to the German bombardment, making it all but impossible to co-ordinate the infantry and artillery.

A brigade reserve unit was ordered to remedy the situation by attacking the Green Crassier slagheap and the mine complex at Fosse St Louis.

[61] The Germans refrained from attempts to recapture the lost ground at Lens, due to the need to avoid diverting resources from the Third Battle of Ypres in Flanders, the main strategic effort on the Western Front by both sides.

The frontal attacks on 21 and 23 August were rash and demonstrated that Currie lacked experience; Cook placed blame on Watson and Hilliam, the latter of whom should have been sacked.

[67] In the History of the Great War (1948), the British official historian, James Edmonds wrote that from 15 to 23 August, the 1st Canadian Division suffered 3,035 casualties, 881 being fatal.

In Surviving Trench Warfare (1992) Bill Rawling wrote that the attack on Hill 70 cost the Canadian Corps 3,527 casualties, 1,056 killed, 2,432 wounded and 39 taken prisoner.

[71] From the rest of August to the beginning of October the front was relatively quiet, with Canadian efforts devoted mainly to preparations for another offensive, although none took place, largely because the First Army lacked sufficient resources for the task.