Hip-hop culture

[18][19] Keith "Cowboy" Wiggins, a member of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, has been credited with coining the term[20] in 1978 while teasing a friend who had just joined the US Army by scat singing, in alternation, the made-up words "hip" and "hop" in a way that mimicked the rhythmic cadence of marching soldiers.

[29] Historically, hip hop arose out of the ruins of a post-industrial and ravaged South Bronx, as a form of expression of urban Black and Latino youth, whom the public and political discourse had written off as marginalized communities.

[35] Music critic Peter Shapiro wrote that Herc's innovation "laid the foundations for hip hop", also noting that "it was another DJ, Grandwizard Theodore, who created its signature flourish in 1977 or 1978" – "scratching".

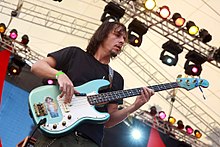

According to Herc, "breaking" was also street slang for "getting excited" and "acting energetically"[39] DJs such as Grand Wizzard Theodore, Grandmaster Flash, and Jazzy Jay refined and developed the use of breakbeats, including cutting and scratching.

Influential tunes included Fatback Band's "King Tim III (Personality Jock)", The Sugarhill Gang's "Rapper's Delight", and Kurtis Blow's "Christmas Rappin'", all released in 1979.

[41][dead link] Herc and other DJs would connect their equipment to power lines and perform at venues such as public basketball courts and at 1520 Sedgwick Avenue, Bronx, New York, now officially a historic building.

Sensing that gang members' often violent urges could be turned into creative ones, Afrika Bambaataa founded the Zulu Nation, a loose confederation of street-dance crews, graffiti artists, and rap musicians.

By the late 1970s, the culture had gained media attention, with Billboard magazine printing an article titled "B Beats Bombarding Bronx", commenting on the local phenomenon and mentioning influential figures such as Kool Herc.

[50][full citation needed] Inspired by DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa created a street organization called Universal Zulu Nation, centered around hip hop, as a means to draw teenagers out of gang life, drugs and violence.

[49] The lyrical content of many early rap groups focused on social issues, most notably in the seminal track "The Message" (1982) by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, which discussed the realities of life in the housing projects.

[60] Other groundbreaking records released in 1982 include "The Message" by Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, "Nunk" by Warp 9, "Hip Hop, Be Bop (Don't Stop)" by Man Parrish, "Magic Wand" by Whodini, and "Buffalo Gals" by Malcolm McLaren.

In 1983, Hashim created the influential electro funk tune "Al-Naafiysh (The Soul)", while Warp 9's "Light Years Away"(1983), "a cornerstone of early 80s beat box afrofuturism", introduced socially conscious themes from a Sci-Fi perspective, paying homage to music pioneer Sun Ra.

In 1982, Melle Mel and Duke Bootee recorded "The Message" (officially credited to Grandmaster Flash and The Furious Five),[63] a song that foreshadowed the socially conscious statements of Run-DMC's "It's like That" and Public Enemy's "Black Steel in the Hour of Chaos".

This was especially notable in the United Kingdom, where British hip hop grew its own voice and style from the 1980s, with rappers such as She Rockers, MC Duke, and Derek B, followed by Silver Bullet, Monie Love, Caveman, and London Posse.

Considering albums such as N.W.A's Straight Outta Compton, Eazy-E's Eazy-Duz-It, and Ice Cube's AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted were selling in such high numbers meant that black teens were no longer hip hop's sole buying audience.

The album, released in 2004, sold over 4 million copies worldwide,[74] has been noted by critics for its manipulation of samples, many pulled from pop culture, where West would speed up or slow down the original beat, a trend that became popular as a result.

Hip hop has played a small but distinct role as the musical face of revolution in the Arab Spring, one example being an anonymous Libyan musician, Ibn Thabit, whose anti-government songs fueled the rebellion.

[96] White pop rappers such as Macklemore, Iggy Azalea, Machine Gun Kelly, Eminem, Miley Cyrus, G-Eazy, and Post Malone have often been criticized for commercializing hip hop and cultural appropriation.

[113] MCing is a form of expression that is embedded within ancient African and Indigenous culture and oral tradition as throughout history verbal acrobatics or jousting involving rhymes were common within the Afro-American and Latino-American community.

[125][126] The early trend-setters were joined in the 1970s by artists like Dondi, Futura 2000, Daze, Blade, Lee Quiñones, Fab Five Freddy, Zephyr, Rammellzee, Crash, Kel, NOC 167 and Lady Pink.

Source material include the spirituals of slaves arriving in the new world, Jamaican dub music, the laments of jazz and blues singers, patterned cockney slang and radio deejays hyping their audience using rhymes.

[157] Some academics, including Ernest Morrell and Jeffrey Duncan-Andrade, compare hip hop to the satirical works of great "Western canon" poets of the modern era, who use imagery and create a mood to criticize society.

The result – which sometimes renders the remaining lyrics unintelligible or contradictory to the original recording – has become almost as widely identified with the genre as any other aspect of the music, and has been parodied in films such as Austin Powers in Goldmember, in which Mike Myers' character Dr.

Professor Louis Gates testified on behalf of The 2 Live Crew, arguing that the material that the county alleged was profane actually had important roots in African-American vernacular, games, and literary traditions and should be protected.

The show was exemplified by music videos such as "Tip Drill" by Nelly, which was criticized for what many viewed as an exploitative depiction of women, particularly images of a man swiping a credit card between a stripper's buttocks.

With merchandise such as dolls, commercials for soft drinks and numerous television show appearances, Hammer began the trend of rap artists being accepted as mainstream pitchpeople for brands.

Hilfiger's success convinced other large mainstream American fashion design companies, like Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein, to tailor lines to the lucrative market of hip hop artists and fans.

Hip Hop is thus to modern day as Negro Spirituals are to the plantations of the old South: the emergent music articulates the terrors of one's environment better than written, or spoken word, thereby forging an "unquestioned association of oppression with creativity [that] is endemic" to African American culture".

[211] However, while the pervasive oppressive conditions of the Bronx were likely to produce another group of disadvantaged youth, he questions whether they would be equally interested, nonetheless willing to put in as much time and energy into making music as Grandmaster Flash, DJ Kool Herc, and Afrika Bambaataa.

[222] Gilroy states that the "power of [hip hop] music [lies] in developing black struggles by communicating information, organizing consciousness, and testing out or deploying ... individual or collective" forms of African-American cultural and political actions.