Hispano-Arabic homoerotic poetry

Among the Andalusi kings the practice of homosexuality with young men was quite common; among them, the Abbadid emir Al-Mu'tamid of Seville and Yusuf III of the Nasrid kingdom of Granada wrote homoerotic poetry.

[4] The contradiction between the condemnatory religious legality and the permissive popular reality was overcome by resorting to a neoplatonic sublimation, the "udri love", of an ambiguous chastity.

[5] The object of desire, generally a servant, slave or captive, inverted the social role in poetry, becoming the owner of the lover, in the same way as happened with courtly love in medieval Christian Europe.

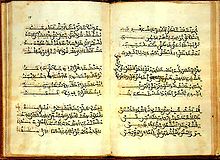

[1] Much of the erotic-amorous poetry of the period is devoted to the cupbearer or wine pourer, combining the bacchic (خمريات jamriyyat) and homoerotic (مذكرات mudhakkarat) genres.

[9] The fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the eleventh century and the subsequent rule of the Almoravids and the division into the Taifa kingdoms, decentralized culture throughout al-Andalus, producing an era of splendor in poetry.

Anthologies of medieval Islamic poetry from the great Arab capitals show, over almost a millennium, the same current of passionate homoeroticism found in the poems of Córdoba, Seville or Granada.

[9] Homosexuality, consented to on the basis of a general Koranic tolerance towards sins of the flesh, was introduced as a cultural refinement among the Umayyads, despite the protests of some juridical schools.

Thus, Ibn Hazm of Córdoba was tolerant of homoeroticism,[12] showing his reprobation only when it was mixed with some kind of public immorality, an attitude apparently shared by his contemporaries.

[9] While in the rest of Europe it was punishable by burning at the stake, in al-Andalus homosexuality was common and intellectually prestigious; the work of authors such as Ibn Sahl of Seville, explicit in this sense, was carried to all corners of the Islamic world as an example of love poetry.

[17] The Australian historian Robert Aldrich points out that in part this tolerance towards homoeroticism is due to the fact that Islam does not recognize such a marked separation between the flesh and the spirit as Christianity does and has an appreciation for sexual pleasure.

Homosexual pleasure was not only frequent, but was considered more refined among the well-to-do and educated; apparently, there is data indicating that Sevillian male prostitutes in the early 12th century were paid more than their female counterparts, and had a higher class clientele.

[1] Homosexual love (مذكرات mudhakkarat) as a literary theme occurred in the realm of poetry throughout the Arab world; the Persian jurist and litterateur Muhammad ibn Dawud (868 - 909) wrote, at the age of 16, the Book of the Flower, an anthology of the stereotypes of the love lyric that devotes ample space to homoerotic verses;[18] Emilio García Gómez points out that Ibn Dawud's anguish, due to the homoerotic passion he felt all his life towards one of his schoolmates (to whom he dedicated the book), was a spring that led him to realize a platonism that García Gómez identifies as a "collective yearning" in Arab culture to redirect a "noble spiritual flow" that found no way out.

Ibn Dawud clothed it with the Arab myth of "udri love", whose name comes from the tribe of the Banu Udra, which would literally mean "Sons of Virginity": a refined idealism created by Eastern rhetoricians, an "ambiguous chastity", according to García Gómez, which was "a morbid perpetuation of desire".

[1] Another poet who sang of the illicit pleasures of wine and ephebes was Abū Nuwās al-Hasan Ibn Hāni' al-Hakamī, better known simply as Abu Nuwas (Ahvaz, Iran, 747 - Baghdad, 815).

The homoerotic love he celebrated is similar to that described in ancient Greece: the adult poet assumes an active role opposite a young adolescent who submits.

Thus, the age difference between lover and beloved was crucial in a homosexual relationship; hence the appearance of facial hair on the ephebe was an extremely popular topos in Arab homoerotic poetry, because it marked the transition to an untenable situation, although it immediately generated a response in defense of the beauty maintained in a fully bearded young man.

[24][25] The erotic genre qasida was known as nasib, and was closely linked with ogniya, verses adapted to song and musical accompaniment, cultivated by numerous female poets.

Thus, some poets were more explicit and less chaste in the expression of their passion, as Ali ibn Abi l-Husayn (m. 1038):[1] How many nights I have been served drinksby the hands of a roe deer that commits me!He made me drink from his eyes and from his handand it was drunkenness upon drunkenness, passion upon passion.I would take kisses from her cheeks and dip my lipsin her mouth, both sweeter than honey.It was relatively frequent in Arabic love poetry that the object of desire was a slave or captive.

Ar-Ramadi, panegyrist of Almanzor and one of the most prominent Cordovan poets of the 10th century, became so enamored of a young Christian that he made the sign of the cross when he drank wine.

In his poetry, which combined the classical currents of Bedouin tradition with modernist renovations, he practiced the genre of self-praise or boasting (fajr), displaying both his homosexuality and his ascription to Shiism, a faction of Islam persecuted in his time by the Umayyads.

In the qasida with which the poet answered him, he mocked the Abbadids, Al-Mutamid's wife and children, and accused him of sodomy, recalling the days of Silves:[10] I embraced your tender waist,I drank clear water from your mouth.I was content with what was permitted,but you wanted that which is not.I will expose that which you conceal:Oh glory of chivalry!You defended the villages,but you raped the people.When Al-Mutamid was later able to apprehend Ibn Ammar, he pardoned him, but when he learned that the latter was boasting of his pardon, he flew into a rage and killed him with his own hands.

He stood out especially for the development of the modernist theme of the garden (rawdyyāt), to the point that the lyric on nature was called in al-Ándalus, in reference to his surname, jafayyi style.

In his poetry he made subtle chaining of images, loaded with connotations to other themes, including homoeroticism; in a rawdiyyat, the description of a garden introduces a smile, an army, the wine in his cup which is a horse and ends in a beautiful young man.

[10] Indicative is the use of the term "moon" (of masculine gender in Arabic) to refer to the young man:[1] The wine is struck down and falls on its face,expelling from its mouth a violent aroma;the cup is a sorrel horse that is running in circles,with a sweat in which bubbles flow;it runs with the wine and the cup, a moonwith a beautiful face and a honeyed smile;armed to the nines, in its waist and in its gaze,there are also weapons and penetrating swords.The invasion of Al-Andalus by the Almohads (al-Muwahhidūn, "those who recognize the unity of God"), coming from Morocco, provoked the emergence of new literary courts in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Describing an ephebe, in verses that combine the lexicalized comparison of curly water as a coat of mail and the reddish color of oranges, Safwan ibn Idris of Murcia (1165-1202) wrote: A gazelle full of coquetry,which sometimes pleases us and sometimes frightens us;he throws oranges into a poollike one who stains a coat of mail with blood.It is as if he throws the hearts of his loversinto the abyss of a sea of tears.Also noteworthy is the famed Muhammad Ibn Galib, known as al-Rusafi (d. 1177), born in al-Rusafa (present-day Ruzafa, in Valencia) but settled in Málaga.

[11] One of the poems dedicated to his first lover is a sample of the preciousness of the time and the images of "second power", where the sideburns resemble the legs of scorpions and the eyes resemble arrows or swords: Is it a sun with a purplerobe or a moon ascending on a willow branch?Does it show teeth or are they strung pearls?Are those eyes that it has or two lions?An apple cheek or a rosethat from scorpions keeps two swords?Although the situation of Andalusian women was one of seclusion behind the veil and the harem, there were some among the upper classes who, being only daughters or without male siblings, were liberated by remaining single.

In one of their poems, the passion of one of the sisters for a young girl is expressed, leaving the doubt as to whether it is really homoeroticism or a mere literary cliché:[11] That is the reason that prevents me from sleeping:when she lets her curls loose over her face,she looks like the moon in the darkness of the night;it is as if the dawn has lost a brotherand sadness has dressed itself in mourning.It is worth mentioning the figure of Princess Wallada bint al-Mustakfi (994–1077 or 1091), who has been called "the Andalusian Sappho".

[39] Daughter of the Caliph of Córdoba Muhammad III, the death of her father in 1025 left her a fortune in inheritance that allowed her to turn her home into a place of passage for writers.