Historical climatology

It is concerned with the reconstruction of weather and climate and their effect on historical societies, including a culturally influenced history of science and perception.

These historical impacts of climate change can improve human life and cause societies to flourish, or can be instrumental in civilization's societal collapse.

The primary sources include written records such as sagas, chronicles, maps and local history literature as well as pictorial representations such as paintings, drawings and even rock art.

[2] The Palgrave Handbook of Climate History provides a comprehensive overview of the methods and results of historical climatology in a global context.

Historical climatology has created an interface between narrative and proxy data in the form of an index that allows a numerical evaluation of documentary weather reports.

On the one hand, the narrative data describe the weather pattern and its effects on the human environment, but the associated estimation of the temperature and precipitation conditions is subjective.

[5] The proxy data on the other hand enable temperature and precipitation conditions to be assessed, but they do not allow concluding to the detailed weather pattern and its effects on society.

Researchers have proposed that the regional environment transitioned from humid jungle to more arid grasslands due to tectonic uplift[7] and changes in broader patterns of ocean and atmospheric circulation.

[9] Rapid tectonic uplift likely occurred in the early Pleistocene,[8] changing the local elevation and broadly reorganizing the regional patterns of atmospheric circulation.

[8] It is difficult to differentiate correlation from causality in these paleopanthropological and paleoclimatological reconstructions, so these results must be interpreted with caution and related to the appropriate time-scales and uncertainties.

Before the retreat of glaciers at the start of the Holocene (~9600 BC), ice sheets covered much of the northern latitudes and sea levels were much lower than they are today.

[13][14] The effect of climate on available resources and living conditions such as food, water, and temperature drove the movement of populations and determined the ability for groups to begin a system of agriculture or continue a foraging lifestyle.

[13] Groups such as the inhabitants of northern Peru and central Chile,[15] the Saqqaq in Greenland,[16] nomadic Eurasian tribes in Historical China,[17] and the Natufian culture in the Levant all display migration reactions due to climatic change.

[13] In northern Peru and central Chile climate change is cited as the driving force in a series of migration patterns from about 15,000 B.C.

evidence suggests seasonal migration from high to low elevation by the natives while conditions permitted a humid environment to persist in both areas.

The correlation between climate and migratory patterns leads historians to believe the Central Chilean natives favored humid, low-elevation areas especially during periods of increased aridity.

[19] Evidence of a warm climate in Europe, for example, comes from archaeological studies of settlement and farming in the Early Bronze Age at altitudes now beyond cultivation, such as Dartmoor, Exmoor, the Lake District and the Pennines in Great Britain.

Some parts of the present Saharan desert may have been populated when the climate was cooler and wetter, judging by cave art and other signs of settlement in Prehistoric Central North Africa.

[23] Other, smaller communities such as the Viking settlement of Greenland[24] have also suffered collapse with climate change being a suggested contributory factor.

The environmental approach uses paleoclimatic evidence to show that movements in the Intertropical Convergence Zone likely caused severe, extended droughts during a few time periods at the end of the archaeological record for the classic Maya.

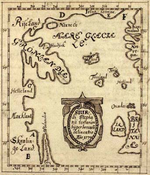

Archaeological evidence supports studies of the Norse sagas which describe the settlement of Greenland in the 9th century AD of land now quite unsuitable for cultivation.

[30] The same period records the discovery of an area called Vinland, probably in North America, which may also have been warmer than at present, judging by the alleged presence of grape vines.

The first Thames frost fair was in 1607; the last in 1814, although changes to the bridges and the addition of an embankment affected the river flow and depth, diminishing the possibility of freezes.

The winter of 1794/1795 was particularly harsh when the French invasion army under Pichegru could march on the frozen rivers of the Netherlands, while the Dutch fleet was fixed in the ice in Den Helder harbour.

The Norse colonies in Greenland starved and vanished (by the 15th century) as crops failed and livestock could not be maintained through increasingly harsh winters, though Jared Diamond noted that they had exceeded the agricultural carrying capacity before then.