Historical immigration to Great Britain

The historical immigration to Great Britain concerns the movement of people, cultural and ethnic groups to the British Isles before Irish independence in 1922.

Modern humans first arrived in Great Britain during the Palaeolithic era, but until the invasion of the Romans (1st century BC) there was no historical record.

With the Fall of the Western Roman Empire, large numbers of Germanic speakers from the continent migrated to the southern parts of the island, becoming known as the Anglo-Saxons and eventually forming England.

[14] More than 90% of Britain's Neolithic gene pool was replaced with the arrival of the Bell Beaker people,[15] who had approximately 50% WSH ancestry.

Initially an oppressive rule, gradually the new leaders gained a firmer hold on their new territory which at one point stretched from the south coast of England to Wales and northwards as far as southern Scotland.

It was with constant contact with Rome and the rest of Romanised Europe through trade and industry that the elite native Britons themselves adopted Roman culture and customs, such as the Latin language, though the majority in the countryside were little affected.

Though the (probably mythical) landing of Hengist and Horsa in Kent in 449 is traditionally considered to be the start of the Anglo-Saxon migrations, archaeological evidence has shown that significant settlement in East Anglia predated this by nearly half a century.

[30] The key area of large-scale migration was southeastern Britain; in this region, place names of Celtic and Latin origin are extremely few.

[31][32][33][34] Genetic and isotope evidence has demonstrated that the settlers included both men and women, many of whom were of a low socioeconomic status, and that migration continued over an extended period, possibly more than two hundred years.

In the Post-Roman period the traditional division of the Anglo-Saxons into Angles, Saxons and Jutes is first seen in the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum by Bede; however, historical and archaeological research has shown that a wider range of Germanic peoples from Frisia, Lower Saxony, Jutland and possibly southern Sweden moved to Britain during this period.

Their formation has been linked to a second stage of Anglo-Saxon expansion in which the kingdoms of Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria each began periods of conquest of British territory.

[39] That this was the case is demonstrated by the late seventh century laws of King Ine, which made specific provisions for Britons who lived in Wessex.

These raiders, whose expeditions extended well into the 9th century, were gradually followed by armies and settlers who brought a new culture and tradition markedly different from that of the prevalent Anglo-Saxon society of southern Britain.

Though located formally within the Danelaw, counties such as Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, and Essex do not seem to have experienced much Danish settlement, which was more concentrated in Yorkshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire, as demonstrated by toponymic evidence.

Settlement was densest in the Shetland and Orkney islands and Caithness, where Norn, a language descended from Old Norse, was historically spoken, but a Viking presence has also been identified in the Hebrides and the western Scottish Highlands.

[42][43] The Norman conquest of 1066 is normally considered the last successful attempt in history by a foreign army to take control of the Kingdom of England by means of military occupation.

From the Norman point of view, William the Conqueror was the legitimate heir to the realm (as explained in the Bayeux Tapestry), and the invasion was required to secure this against the usurpation of Harold Godwinson.

[45] In the years following the invasion to 1204, when Normandy was lost to France, the new nobility maintained close ties with their homelands across the channel.

The influx of Norman military and ecclesiastical aristocracy changed the nature of the ruling class in England, leading to the creation of an Anglo-Norman population.

Some French nobles moved north to Scotland at the invitation of King David I, where they established many of the royal houses that would dominate Scottish politics in the coming centuries.

[53] The Huguenots, French Protestants facing persecution following the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, began to move to England in large numbers around 1670, after King Charles II offered them sanctuary.

There were also some ayahs, domestic servants and nannies of wealthy British families, who accompanied their employers back to "Blighty" when their stay in Asia came to an end.

The number of seamen from the East Indies employed on English ships was felt so worrisome at that time that the English tried to restrict their numbers by the Navigation Act 1660, which restricted the employment of overseas sailors to a quarter of the crew on returning East India Company ships.

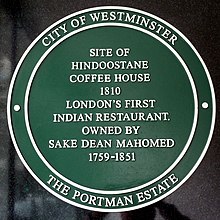

By the mid-19th century, there were at least 40,000 Indian seamen, diplomats, scholars, soldiers, officials, tourists, businessmen and students in Great Britain.

[63] [64] [65][66][67] [68][69] There has been continuous migration from Ireland to Britain since before the Middle Ages, but the number of arrivals increased significantly in the nineteenth century, due to the Great Famine and job opportunities offered by the Industrial Revolution.

[70][71] Following the British defeat in the American War of Independence over 1,100 Black Loyalist troops who had fought on the losing side were transported to Britain, but they mostly ended up destitute on London's streets and were viewed as a social problem.

[73] This community maintained its size until the First World War, when public anti-German feeling became very prominent and the Government enacted a policy of forced internment and repatriation.

The most recent work, carried out using data collected from ancient skeletons, has suggested that the migration events which most drastically influenced the genetic makeup of the current British population were the arrival of the Bell Beaker people around 2500 BC, and the influx of the Anglo-Saxons following the Roman withdrawal.

[82][83][84] Studies of DNA suggest that the biological influence on Britain of immigration from the Norman conquests up until the 20th century was small; The native population's genetics was marked more by stability than change.

[85][86] Modern genetic evidence, based on analysis of the Y chromosomes of men currently living in Britain, the Western Isles, Orkney, Shetland, Friesland, Denmark, North Germany, Ireland, Norway and the Basque Country, is consistent with the presence of some indigenous component in all British regions.