History of Bahrain

[1] Dilmun appears first in Sumerian cuneiform clay tablets dated to the end of fourth millennium BC, found in the temple of goddess Inanna, in the city of Uruk.

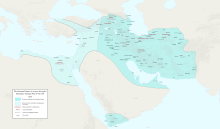

[3] There is both literary and archaeological evidence of extensive trade between Ancient Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley civilization (probably correctly identified with the land called Meluhha in Akkadian).

The "Persian Gulf" types of circular, stamped (rather than rolled) seals known from Dilmun, that appear at Lothal in Gujarat, India, and Failaka, as well as in Mesopotamia, are convincing corroboration of the long-distance sea trade.

He recorded: "That in the island of Tylos, situated in the Persian Gulf, are large plantations of cotton tree, from which are manufactured clothes called sindones, with very different degrees of value, some being costly, others less expensive.

"[16] The Greek historian, Theophrastus, states that many of the islands were covered in these cotton trees and that Tylos was famous for exporting walking canes engraved with emblems that were customarily carried in Babylon.

From the 4th (Sasanian Empire) to the 8th century (Islamic Caliphate) the Bahraini population followed Nestorian Christianity also known as the "Eastern Church", temple ruins related to that period was found in Samahij (originally referred to as "Meshmahij").

After Baghdad emerged as the seat of the caliph in 750 and the main centre of Islamic civilization, Bahrain greatly benefited from the city's increased demand for foreign goods especially from China and South Asia.

The land they ruled over was extremely wealthy with a huge slave-based economy according to academic Yitzhak Nakash: The Qarmatian state had vast fruit and grain estates both on the islands and in Hasa and Qatif.

In 1253, the Bahrani dynasty of the Usfurids of Banu Uqayl – named after its founder, Usfur ibn Rashid – gained control over eastern Arabia, including the islands of Bahrain.

The late Middle Ages were a time of chronic instability with local disputes allowing various Persian-based Arab Kingdoms based in Qais, Qishm and Hormuz to involve themselves in Bahrain's affairs.

The Safavid's used the clergy to buttress their rule, hoping that by firmly implanting Imami Shiaism they could secure the islands of Bahrain, with their centrality to trade routes and pearl wealth.

According to a contemporary account by theologian, Sheikh Yusuf Al Bahrani, in an unsuccessful attempt by the Persians and their Bedouin allies to take back Bahrain from the Kharijite Omanis, much of the country was burnt to the ground.

[70] In 1782, war broke out between the army of Sheikh Nasr Al-Madhkur, the ruler of Bahrain and Bushehr and the Zubarah-based Bani Utbah clan, though hostilities arose since 1777 after the Persians saw the Zubarah base as a threat.

The Persians launched an assault of Zubarah's fort but were forced to break the siege after suffering stiff resistance from the Al Khalifa defenders and facing imminent naval reinforcements from Bani Utbah men in Kuwait.

[71]: 38 The most probable version, as put forward by Historian J. G. Lorimer, was that the invasion was led by Ahmed Al Fateh in 1783 and that he defeated Nasr Al-Madhkur in battle on the outskirts of Manama and plundered the town.

Shortly after the fighting had taken place, Mohammed bin Thani, an influential tribal leader in Al Bidda, pursued a separate peace agreement with Faisal and agreed to his governance, a move seen as a betrayal by the Bahrainis.

Despite waves of migration that brought a diverse mix of merchants, financiers, craftsmen, and laborers from across the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean, the Shi'i Baharna remained the majority population.

Bahrain was no longer dependent upon pearling, and by the mid-19th century, it became the pre-eminent trading centre in the Persian Gulf, overtaking rivals Basra, Kuwait, and finally in the 1870s, Muscat.

A contemporary account of Manama in 1862 found: Mixed with the indigenous population [of Manamah] are numerous strangers and settlers, some of whom have been established here for many generations back, attracted from other lands by the profits of either commerce or the pearl fishery, and still retaining more or less the physiognomy and garb of their native countries.

Thus the gay-coloured dress of the southern Persian, the saffron-stained vest of Oman, the white robe of Nejed, and the striped gown of Bagdad, are often to be seen mingling with the light garments of Bahreyn, its blue and red turban, its white silk-fringed cloth worn Banian fashion round the waist, and its frock-like overall; while a small but unmistakable colony of Indians, merchants by profession, and mainly from Guzerat, Cutch, and their vicinity, keep up here all their peculiarities of costume and manner, and live among the motley crowd, 'among them, but not of them'.

[104] Bahrain underwent a period of major social reform between 1926 and 1957, under the de facto rule of Charles Belgrave, the British advisor to Shaikh Hamad ibn Isa Al-Khalifa (1872-1942).

Relations with the United Kingdom became closer, as evidenced by the British Royal Navy moving its entire Middle Eastern command from Bushehr in Iran to Bahrain in 1935.

The riots focused on the Jewish community, which included distinguished writers, singers, accountants, engineers and middle managers working for the oil company, textile merchants with business all over the peninsula, and free professionals.

Following riots in support of Egypt defending itself against the tripartite invasion during 1956 Suez Crisis, the British decided to put an end to the NUC challenge to their presence in Bahrain.

Although the Assembly and then-Emir Isa ibn Salman al-Khalifa quarrelled over a number of issues (foreign policy; the U.S. naval presence, and the budget), the biggest clash came over the State Security Law (SSL).

The attempted coup and the outbreak of the Iran–Iraq War led to the formation of the Gulf Cooperation Council, which Bahrain joined with Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

[130] The protests in Bahrain started on 14 February, and were initially aimed at achieving greater political freedom and respect for human rights; they were not intended to directly threaten the monarchy.

[135] King Hamad bin Isa Al Khalifa declared a three-month state of emergency on 15 March and asked the military to reassert its control as clashes spread across the country.

[131]: 287,288 On 23 November 2011 the Bahrain Independent Commission of Inquiry released its report on its investigation of the events, finding that the government had systematically tortured prisoners and committed other human rights violations.

[154] Although the report found that systematic torture had stopped,[131]: 417 the Bahraini government has refused entry to several international human rights groups and news organizations, and delayed a visit by a UN inspector.