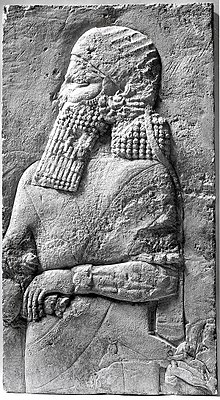

Sennacherib

During Sargon's longer absences from the Assyrian heartland, Sennacherib's residence would have served as the center of government in the Neo-Assyrian Empire, with the crown prince taking on significant administrative and political responsibilities.

[22] By the time Sennacherib became king, the Neo-Assyrian Empire had been the dominant power in the Near East for over thirty years, chiefly due to its well-trained and large army, superior to that of any other contemporary kingdom.

Though old native Babylonians ruled most of the cities, such as Kish, Ur, Uruk, Borsippa, Nippur, and Babylon itself, Chaldean tribes led by chieftains who often squabbled with each other dominated most of the southernmost land.

[29] Even with this public denial in mind, Sennacherib was superstitious and spent a great deal of time asking his diviners what kind of sin Sargon could have committed to suffer the fate that he had, perhaps considering the possibility that he had offended Babylon's deities by taking control of the city.

First, a Babylonian by the name of Marduk-zakir-shumi II took the throne, but Marduk-apla-iddina, the same Chaldean warlord who had seized control of the city once before and had warred against Sennacherib's father, deposed him after just two[33] or four weeks.

[7] Marduk-apla-iddina rallied large portions of Babylonia's people to fight for him, both the urban Babylonians and the tribal Chaldeans, and he also enlisted troops from the neighboring civilization of Elam, in modern-day south-western Iran.

Though assembling all these forces took time, Sennacherib reacted slowly to these developments, which allowed Marduk-apla-iddina to station large contingents at the cities of Kutha and Kish.

[42] After a brief period of rest in Babylon, Sennacherib and the Assyrian army then moved systematically through southern Babylonia, where there was still organized resistance, pacifying both the tribal areas and the major cities.

[4] In 705 BC, Hezekiah, the king of Judah, had stopped paying his annual tribute to the Assyrians and began pursuing a markedly aggressive foreign policy, probably inspired by the recent wave of anti-Assyrian rebellions across the empire.

Faced with a massive Assyrian army nearby, many of the Levantine rulers, including Budu-ilu of Ammon, Kammusu-nadbi of Moab, Mitinti of Ashdod and Aya-ramu of Edom, quickly submitted to Sennacherib to avoid retribution.

[48] According to the Biblical narrative, a senior Assyrian official with the title Rabshakeh stood in front of the city's walls and demanded its surrender, threatening that the Judeans would 'eat feces and drink urine' during the siege.

As an Assyrian king of Babylon, Ashur-nadin-shumi's position was politically important and highly delicate and would have granted him valuable experience as the intended heir to the entire Neo-Assyrian Empire.

Through some unknown means, Sennacherib had managed to slip by the Babylonian and Elamite forces undetected some months prior and was not present at the final battle, instead probably being on his way from Assyria with additional troops.

The rebel Shuzubu, hunted by Sennacherib in his 700 BC invasion of the south, had resurfaced under the name Mushezib-Marduk and, seemingly without foreign support, acceded to the throne of Babylon.

[73] In 1973, the Assyriologist John A. Brinkman wrote that it was likely that the southerners won the battle, though probably suffering many casualties, since both of Sennacherib's enemies still remained on their respective thrones after the fighting.

[91] The text of the inscription, written in an unusually intimate way, reads:[92] And for the queen Tashmetu-sharrat, my beloved wife, whose features Belet-ili has made more beautiful than all other women, I had a palace of love, joy and pleasure built.

He built a large second palace at the city's southern mound, which served as an arsenal to store military equipment and as permanent quarters for part of the Assyrian standing army.

[96] He concluded a "treaty of rebellion" with another of his younger brothers, Nabu-shar-usur, and on 20 October 681 BC, they attacked and killed their father in one of Nineveh's temples,[94] possibly the one dedicated to Sîn.

The denizens of the Levant and Babylonia celebrated the news and proclaimed the act as divine punishment because of Sennacherib's brutal campaigns against them, while in Assyria the reaction was probably resentment and horror.

Like the inscriptions of other Assyrian kings, his show pride and high self-esteem, for instance in the passage: "Ashur, father of the gods, looked steadfastly upon me among all the rulers and he made my weapons greater than (those of) all who sit on (royal) daises."

In several places, Sennacherib's great intelligence is emphasized, for instance in the passage, "the god Ninshiku gave me wide understanding equal to (that of) the sage Adapu (and) endowed me with broad knowledge".

Sennacherib assumed several new epithets never used by Assyrian kings, such as "guardian of the right" and "lover of justice", suggesting a desire to leave a personal mark on a new era beginning with his reign.

Most of Sennacherib's campaigns were not aimed at conquest, but at suppressing revolts against his rule, restoring lost territories and securing treasure to finance his building projects.

[36] What the alû demon was is not entirely understood, but the typical symptoms described in contemporary documents include the afflicted not knowing who they are, their pupils constricting, their limbs being tense, being incapable of speech and their ears roaring.

The first reason for this is Sennacherib's negative portrayal in the Bible as the evil conqueror who attempted to take Jerusalem; the second is his destruction of Babylon, one of the most prominent cities in the ancient world.

Medieval Syriac tales characterize Sennacherib as an archetypical pagan king assassinated as part of a family feud, whose children convert to Christianity.

In Midrash, examinations of the Old Testament and later stories, the events of 701 BC are often explored in detail; many times featuring massive armies deployed by Sennacherib and pointing out how he repeatedly consulted astrologers on his campaign, delaying his actions.

Robert and Jean Hollander, Doubleday, 2003 The discovery of Sennacherib's own inscriptions in the 19th century, in which brutal and cruel acts such as ordering the throats of his Elamite enemies to be slit, and their hands and lips cut off, amplified his already ferocious reputation.

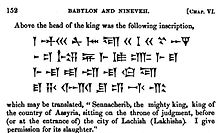

[124] Sennacherib's own accounts of his building projects and military campaigns, typically referred to as his "annals", were often copied several times and spread throughout the Neo-Assyrian Empire during his reign.

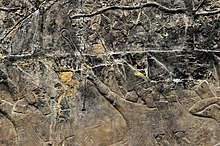

First discovered and excavated from 1847 to 1851 by the British archaeologist Austen Henry Layard, the discovery of reliefs depicting Sennacherib's siege of Lachish in the Southwest Palace was the first archaeological confirmation of an event described in the Bible.