History of Bavaria

The history of Bavaria stretches from its earliest settlement and its formation as a stem duchy in the 6th century through its inclusion in the Holy Roman Empire to its status as an independent kingdom and finally as a large Bundesland (state) of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Archaeological evidence dating from the 5th and 6th centuries points to social and cultural influences from several regions and peoples, such as Alamanni, Lombards, Thuringians, Goths, Bohemian Slavs and the local Romanised population.

Moreover, during the early years of the reign of Charlemagne, Tassilo gave decisions in ecclesiastical and civil causes in his own name, refused to appear in the assemblies of the Franks, and in general acted as an independent ruler.

During the reign of Louis the Child, Luitpold, Count of Scheyern, who possessed large Bavarian domains, ruled the Mark of Carinthia, created on the southeastern frontier for the defense of Bavaria.

In 1070 AD, King Henry IV deposed duke Otto, granting the duchy to Count Welf, a member of an influential Bavarian family with roots in northern Italy.

The increasing importance of former Bavarian territories like the March of Styria (erected into a duchy in 1180 AD) and of the county of Tyrol had diminished both the actual and the relative strength of Bavaria, which now on almost all sides lacked opportunities for expansion.

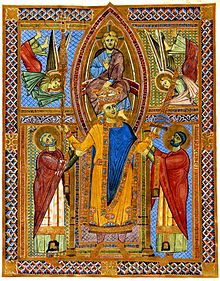

A new era began when, in consequence of Henry the Lion being placed under an imperial ban in 1180 AD, Emperor Frederick I awarded the duchy to Otto, a member of the old Bavarian family of Wittelsbach and a descendant of the counts of Scheyern.

The efforts of the dukes to increase their power and to give unity to the duchy had met with a fair measure of success; but they were soon vitiated by partitions among different members of the family, which for 250 years made the history of Bavaria little more than a repetitive chronicle of territorial divisions bringing war and weakness in their wake.

Rupert died in 1504, and the following year an arrangement was made at the Diet of Cologne by which the emperor and Philip's grandson, Otto Henry, obtained certain outlying districts, while Albert by securing the bulk of George's possessions united Bavaria under his rule.

This link strengthened in 1546, when the emperor Charles V obtained the help of the duke during the war of the league of Schmalkalden by promising him in certain eventualities the succession to the Bohemian throne, and the electoral dignity enjoyed by the count palatine of the Rhine.

Early in his reign Albert made some concessions to the reformers, who were still strong in Bavaria; but about 1563 he changed his attitude, favored the decrees of the Council of Trent, and pressed forward the work of the Counter-Reformation.

Maximilian's son, Ferdinand Maria (1651–1679), who was a minor when he succeeded, tried to repair the wounds caused by the Thirty Years' War, encouraging agriculture and industries and building or restoring numerous churches and monasteries.

His good work, however, was largely undone by his son Maximilian II Emanuel (1679–1726), whose far-reaching ambition set him warring against the Ottoman Empire and, on the side of France, in the great struggle of the Spanish succession.

The price he had to pay, however, was the occupation of Bavaria itself by Austrian troops; and, though the invasion of Bohemia in 1744 by Frederick II of Prussia enabled him to return to Munich, at his death on 20 January 1745 it was left to his successor to make what terms he could for the recovery of his dominions.

Maximilian III Joseph (1745–1777), called "Max the much-beloved", by the peace of Füssen, signed on 22 April 1745, obtained the restitution of his dominions in return for a formal acknowledgment of the Pragmatic Sanction.

Charles Theodore, who had done nothing to prevent wars or to resist the invasion, fled to Saxony and abandoned a regency whose members signed a convention with Moreau, by which he granted an armistice in return for a heavy contribution (7 September 1796).

In place of the old system of privileges and exemptions were set equality before the law, universal liability to taxation, the abolition of serfdom, the security of person and property, liberty of conscience and of the press.

By the treaty signed at Paris on 28 February 1810, Bavaria ceded southern Tirol to Italy and some small districts to Württemberg, receiving as compensation parts of Salzburg, the Innviertel and Hausruck and the principalities of Bayreuth and Regensburg.

Immediately after the first peace of Paris (1814), Bavaria ceded to Austria the northern Tyrol and Vorarlberg; during the Congress of Vienna it was decided that she was to add to these the greater part of Salzburg and the Innviertel and Hausruck [de].

But with the collapse of France, the old fears and jealousies against Austria were revived in full force, and Bavaria only agreed to these cessions (treaty of Munich, 16 April 1816) under the promise that, in the event of the powers ignoring her claim to the Baden succession in favor of that of the line of the counts of Hochberg, she should receive also the Palatinate on the right bank of the Rhine.

Prussia, however, refused to approve of any coup d'état; the parliament, chastened by the consciousness that its life depended on the goodwill of the king, moderated its tone; and Maximilian ruled till his death as a model constitutional monarch.

The earlier years of his reign were marked by a liberal spirit and the reform, especially, of the financial administration; but the revolutions of 1830 frightened him into reaction, which was accentuated by the opposition of the parliament to his expenditure on building and works of art.

The Jesuits now gained the upper hand; one by one the liberal provisions of the constitution were modified or annulled; the Protestants were harried and oppressed, and rigorous censorship forbade any free discussion of internal politics.

Lola Montez created Countess Landsfeld, became supreme in the state; and the new minister, Prince Ludwig of Öttingen-Wallerstein (1791–1870), in spite of his efforts to enlist Liberal sympathy by appeals to pan-German patriotism, was powerless to form a stable government.

The guiding spirit in this anti-Prussian policy, which characterized Bavarian statesmanship up to the war of 1866, was Baron Karl Ludwig von der Pfordten (1811–1880), who became minister for foreign affairs on 19 April 1849.

Bavaria accordingly opposed the Prussian proposals for the reorganization of the Confederation, and one of the last acts of King Maximilian was to take a conspicuous part in the assembly of princes summoned to Frankfurt in 1863 by the emperor Francis Joseph.

In the complicated Schleswig-Holstein question Bavaria, under Pfordten's guidance, consistently opposed Prussia, and headed the lesser states in their support of Frederick of Augustenburg against the policy of the two great German powers.

The separatist ambitions of Bavaria were thus formally given up; she had no longer "need of France"; and during the Franco-Prussian War, the Bavarian army marched, under the command of the Prussian crown prince, against Germany's common enemy.

On 31 March 1871, moreover, the bonds with the rest of the empire had been drawn closer by the acceptance of a number of laws of the North German Confederation, of which the most important was the new criminal code, which was finally put into force in Bavaria in 1879.

An attempt supported by a wide coalition of parties, to establish Rupprecht, Crown Prince of Bavaria, as a Staatskommisar with dictatorial powers in 1932 to counter the Nazis failed due to the hesitant Bavarian government under Heinrich Held.