History of Schleswig-Holstein

The old Scandinavian sagas, perhaps dating back to the times of the Angles and Jutes give the impression that Jutland has been divided into a northern and a southern part with the border running along the Kongeå River.

Taking into account both archeological findings and Roman sources, however, one could conclude that the Jutes inhabited both the Kongeå region and the more northern part of the peninsula, while the native Angles lived approximately where the towns Haithabu and Schleswig later would emerge (originally centered in the southeast of Schleswig in Angeln), the Saxons (earlier known apparently as the Reudingi) originally centered in Western Holstein (known historically as "Northalbingia") and Slavic Wagrians, part of the Obodrites (Abodrites) in Eastern Holstein.

As Charlemagne extended his realm in the late 8th century, he met a united Danish army which successfully defended Danevirke, a fortified defensive barrier across the south of the territory west of the Schlei.

For instance, the Holy Roman Emperor Otto II occupied the region between the river Eider and the inlet Schlei in the years 974–983, called the March of Schleswig, and stimulating German colonisation.

The war ended in defeat of the troops under the command of Albert of Orlamünde at Mölln in 1225, and Valdemar was forced to surrender his conquests as the price of his own release and take an oath not to seek revenge.

Holstein on the other hand, after the death of Adolphus IV in 1261, was split up into several countships by his sons and again by his grandsons (1290):[2] the lines of Holstein-Kiel (1261–1390), Holstein-Pinneberg and Schaumburg (1290–1640) south of the Elbe, Holstein-Plön (1290–1350), Holstein-Rendsburg (1290–1459), and at times also Holstein-Itzehoe (1261–1290) and Holstein-Segeberg (1273–1315), and again (1397–1403), all named after the comital residential cities.

King Valdemar III was regarded as a usurper by most Danish nobles as he had been forced by the Schleswig-Holstein nobility to sign the Constitutio Valdemaria (June 7, 1326) promising that The Duchy of Schleswig and the Kingdom of Denmark must never be united under the same ruler.

Duke Valdemar V of Slesvig's son, Henry, was in 1364 nominally entfeoffed with the Duchy, although he never reached to regain more than the northernmost parts as he couldn't raise the necessary funds to repay the loans.

[citation needed] Instead of incorporating South Jutland with the Danish kingdom, however, he preferred to take advantage of the feeling of the estates in Schleswig and Holstein in favour of union to secure both provinces.

Holstein was restored to him by the peace of Frederiksborg in 1720, but in the following year king Frederick IV was recognised as sole sovereign of Schleswig by the estates and by the partitioned-off dukes of the Augustenburg and Glücksburg lines.

[6] Peter III threatened war with Denmark for the recovery of his ancestral lands, but before any fighting could begin he was overthrown by his wife, who took control of Russia as Tsarina Catherine II.

[3] The settlement of 1806 was reversed, and while Schleswig remained as before, the duchies of Holstein and Lauenburg, the latter acquired in personal union by a territorial swap following the Congress of Vienna, were included in the new German Confederation.

When Christian VIII succeeded his first cousin Frederick VI in 1839 the elder male line of the house of Oldenburg was obviously on the point of extinction, the king's only son and heir having no children.

[8] On January 28, Christian VIII issued a rescript proclaiming a new constitution which, while preserving the autonomy of the different parts of the country, incorporated them for common purposes in a single organisation.

The general refused to obey, pleading that he was under the command not of the king of Prussia but of the regent of the German Confederation, Archduke John of Austria, and proposed that, at least, any treaty concluded should be presented for ratification to the Frankfurt Parliament.

Same applied to foreign powers such as Great Britain, France and Russia, who would not accept a weakened Denmark in favour of the German states, nor acquisition of Holstein (with its important naval harbour of Kiel and control of the entrance to the Baltic) by Prussia.

Frederick William's only alternative – an alliance with Louis Napoleon, who already dreamed of acquiring the Rhine frontier for France at the price of his aid in establishing German sea power by the cession of the duchies – was abhorrent to him.

The German Federal Assembly now prepared for armed intervention; but it was in no condition to carry out its threats, and Denmark decided, on the advice of Great Britain, to ignore it and open negotiations directly with Prussia and Austria as independent powers.

Denmark replied with a refusal to recognise the right of any foreign power to interfere in her relations with Schleswig; to which Austria, anxious to conciliate the smaller German princes, responded with a vigorous protest against Danish infringements of the compact of 1852.

[11] Lord John Russell now intervened, on behalf of Great Britain, with a proposal for a settlement of the whole question on the basis of the independence of the duchies under the Danish crown, with a decennial budget for common expenses to be agreed on by the four assemblies, and a supreme council of state consisting in relative proportion of Danes and Germans.

His claim was enthusiastically supported by the German princes and people, and in spite of the negative attitude of Austria and Prussia, the federal assembly at the initiative of Otto von Bismarck decided to occupy Holstein pending the settlement of the decree of succession.

[15] It was clear to Bismarck that Austria and Prussia, as parties to the London Protocol of 1852, must and uphold the succession as fixed by it, and that any action they might take in consequence of the violation of that compact by Denmark must be so correct as to deprive Europe of all excuse for interference.

This implied the recognition of the rights of Christian IX, and was indignantly rejected; whereupon the federal assembly was informed that the Austrian and Prussian governments would act in the matter as independent European powers.

[15] On March 11 a fresh agreement was signed between the powers, under which the compacts of 1852 were declared to be no longer valid, and the position of the duchies within the Danish monarchy as a whole was to be made the subject of a friendly understanding.

[15] Beust, on behalf of the Confederation, demanded the recognition of the Augustenburg claimant; Austria leaned to a settlement on the lines of that of 1852; Prussia, it was increasingly clear, aimed at the acquisition of the duchies.

Meanwhile, in 1864, the Danish royal family, impressed by Victoria's trappings of Empire, arranged the marriage of the Princess to the future Edward VII, so helping to reverse the Anglo-German alliance, which led to the 1914 war.

By Article XIX of the Treaty of 1864, indeed, they should have been secured the rights of indigenacy, which, while falling short of complete citizenship, implied, according to Danish law, all the essential guarantees for civil liberty.

Forty years of dominance, secured by official favour, had filled them with a double measure of aggressive pride of race, and the question of the rival nationalities in Schleswig, like that in Poland, remained a source of trouble and weakness within the frontiers of the German empire.

However, Hitler vetoed any such step, out of a general German policy at the time to base the occupation of Denmark on a kind of accommodation with the Danish Government, and avoid outright confrontations with the Danes.

Though no territorial changes came of it, it had the effect that Prime Minister Knud Kristensen was forced to resign after a vote of no confidence because the Folketing did not support his enthusiasm for incorporating South Schleswig into Denmark.

|

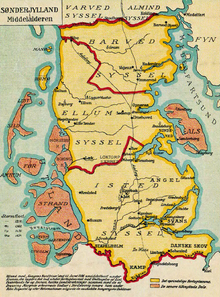

Map of the

Jutland

Peninsula

Northern Jutland

(

Nørrejylland

), i.e. Jutland north of the Kongeå River. In Danish, the region can be subdivided into Nord-, Midt-, and Sydjylland. Not to be confused with "Nordjylland", the latter roughly corresponds to the

North Denmark Region

North Jutlandic Island

; commonly reckoned as part of Jutland, although technically an island, since it was severed from the Jutland Peninsula in 1825 by a flood

Northern Schleswig

(

Nordschleswig

or

Sønderjylland

): Denmark (Middle Ages), part of the

Duchy of Schleswig

(a fief of the Danish crown) 13th century until 1864; German from 1864 until 1920; Danish since 1920

Southern Schleswig

(German since 1864; part of the Duchy of Schleswig (a fief of the Danish crown) until 1864; historically an integral part of Southern Jutland)

Historical area of

Holstein

(

Holsten

), sometimes considered part of Jutland Peninsula – south to the Elbe and the Elbe-Lübeck Canal

|