History of Bermuda

These "tribes" were areas of land partitioned off to the principal "Adventurers" (investors) of the company, from east to west – Bedford, Smiths, Cavendish, Paget, Mansell, Warwick, and Sandys.

[4]: 251–252, 270–272, 279–280, 398 Bermuda and Virginia, as well as Antigua and Barbados were, however, the subjects of the September 1650 Prohibitory Act of the Rump Parliament, and the Atlantic fleet was instructed to bring these opposing colonies into obedience.

This non-dependence on slavery changed however, when the island moved to a maritime economy in the 1690s, and incorporated slave sailors, carpenters, coopers, blacksmiths, masons, and shipwrights.

According to Jarvis, "these small, hot, dry, and barren islands" were perfect for salt production since the limestone, absence of fresh water, and limited rain fall combined to make the soil unfertile.

Yet, average temperatures in the eighties Fahrenheit and the eastern trade wind facilitated evaporation of sea water into a saturated brine for salt crystallized.

[14]: 199, 208–210 The Bahamas, meanwhile, was incurring considerable expense in absorbing loyalist refugees from the now-independent American colonies, and returned to the idea of taxing Turks salt for the needed funds.

With royal administration commencing under Charles II in 1683, and the end of company control in 1684, the island was able to change the basis of its economy from tobacco to maritime enterprises.

[14]: 60–67, 101, 106, 247 [4]: 280, 328 These "Bermuda sloops" had their origin in the ship Jacob Jacobson first built after becoming shipwrecked on the island in 1619, and were based on craft sailing on the Zuiderzee and the Dutch coastal sloep.

The only attack on Bermuda during the war was carried out by two South Carolina sloops captained by a pair of Bermudian-born brothers (they damaged a fort and spiked its guns before retreating).

Lacking political channels with Great Britain, the Tucker Family met in May 1775 with eight other parishioners, and resolved to send delegates to the Continental Congress in July, with the goal of an exemption from the ban.

In late 1775, the British Parliament passed the Prohibitory Act to prohibit trade with the American rebelling colonies, and sent HMS Scorpion to keep watch over the island.

As a result of the large regular army garrison established to protect the naval facilities, Bermuda's parliament allowed the Bermudian militia to become defunct after the end of the American war in 1815.

The post American independence buildup of Royal Navy facilities in Bermuda meant the Admiralty placed less reliance on Bermudian privateers in the area.

As ships became larger, increasingly were built from metal, and with the advent of steam power, and with the vastly reduced opportunities Bermudians found for commerce due to US independence and the greater control exerted over their economies by developing territories, Bermuda's shipbuilding industry and maritime trades were slowly strangled.

By the end of the 19th century, except for the presence of the naval and military facilities, Bermuda was thought of by non-Bermudians and Bermudians alike as a quiet, rustic backwater, completely at odds with the role it had played in the development of the English-speaking Atlantic world, a change that had begun with American independence.

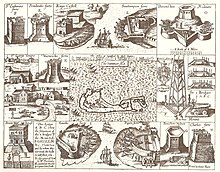

It did this in order to locate the deepwater channel by which shipping might reach the islands in, and at the West of, the Great Sound, which it had begun acquiring with a view to building a naval base.

In 1811, the Royal Navy started building the large dockyard on Ireland Island, in the west of the chain, to serve as its principal naval base guarding the western Atlantic Ocean shipping lanes.

During the War of 1812 between Britain and the United States, the British attacks on Washington, D.C. and the Chesapeake were planned and launched from Bermuda, where the headquarters of the Royal Navy's North American Station had recently been moved from Halifax, Nova Scotia.

In the 1860s, the major build-up of naval and military infrastructure brought vital money into Bermuda at a time when its traditional maritime industries were giving way under the assault of steel hulls and steam propulsion.

The investment into military infrastructure by the War Office proved unsustainable, and poorly thought out, with far too few artillery men available to man the hundreds of guns emplaced.

Still, the important strategic location of Bermuda meant that the withdrawal, which began, at least in intent, in the 1870s, was carried out very slowly over several decades, continuing until after World War I.

[26] In June 1901, The New York Times reported an attempted mutiny by 900 Boer prisoners of war en route to Bermuda on Armenian, noting it was suppressed.

[29] The most famous escapee was the Boer prisoner of war Captain Fritz Joubert Duquesne who was serving a life sentence for "conspiracy against the British government and on (the charge of) espionage.".

[30] On the night of 25 June 1902, Duquesne slipped out of his tent, worked his way over a barbed wire fence, swam 1.5 miles (2.4 km) past patrol boats and bright spot lights, through storm-wracked, using the distant Gibbs Hill Lighthouse for navigation until he arrived ashore on the main island.

[34] In the early 20th century, as modern transport and communication systems developed, Bermuda became a popular destination for American, Canadian and British tourists arriving by sea.

The Royal Naval dockyard on Ireland Island played a role similar to that it had during World War I, overseeing the formation of trans-Atlantic convoys composed of hundreds of ships.

Bermuda became important for British Security Co-ordination operations with the ability to vet radio communication and search passengers and mail using flying boats to transit the Atlantic, with over 1,200 people working on opening packages secretly, finding coded messages, secret writing, micro dots and identifying spies working for Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy and Vichy France in the Americas, much of the information found being passed to the FBI.

The advantage for Britain of granting these base rights was that the neutral US effectively took responsibility for the security of these territories, freeing British forces to be deployed to the sharper ends of the War.

In 1948, regularly scheduled commercial airline service by land-based aeroplanes began to Kindley Field (now L.F. Wade International Airport), helping tourism to reach its peak in the 1960s–1970s.

Another concern, which raised its head during the 1991 Gulf War, was the loss of the protection provided by the Royal Navy, especially to the large number of merchant vessels on Bermuda's shipping register.