History of Cagliari

Around the 16th century Roderigo Hunno Baeza, a Sardinian humanist, stated that the name "Caralis" had derived from the Greek kárs (κάρα, "head"), as Cagliari was the main centre of the island.

Max Leopold Wagner[2] traced the term to Protosardinian Karalis, reflecting the Sardinian place names of Carale (Austis), Carallai (Sorradile), Karhalis or Karhallis (Carallia) of Pamphylia and Karhalleia of Pisidia (Turkey).

A local Renaissance writer, Roderigo Hunno Baeza, describes the Roman city, from the ruins that still remained in his time, as an Arx on the hill, from which the Via Sacra descended to the port.

The very reason for the existence of this ancient city lies in its being both a powerful military structure to defend the main port of southern Sardinia and a basis for control of the western Mediterranean, as well as the outlet for the grain-growing region and livestock products (cheese, leather), iron, lead, copper and zinc mining from the inland, and of course, the salt that was produced at the great saltworks that surround it.

[7] The resources of the sea, ponds, and partly rocky land suitable for cereal and some horticultural crops ensured the livelihood of the people during the peaceful pre-nuragic period.

[8] Archaeological finds from the Bronze Age, such as Aegean pottery found in the nuraghe Antigori of Sarroch, inspired the hypothesis that the Nuragics settled in Cagliari, entertained intense commercial and cultural ties with the Mycenaeans, and are a testimony that their ports were already vital and busy.

[9] The first nucleus of Phoenician Cagliari seems to have been near the pond of Santa Gilla, but gradually the city center moved more and more to the east until it reached approximately the point where today's Piazza del Carmine is located.

During the Punic era, from the end of the 6th century B.C., the city took on the appearance of an authentic urban center and many temples were built, including one dedicated to the goddess Astarte, near the promontory of St. Elias.

[11] The town was also equipped with an amphitheater capable of seating approximately 10,000 spectators, temples, villas and aqueducts that supplied water, sourcing maybe from Domusnovas and Caput Aquas, near Iglesias.

There were at least three cemeteries, one that was the same Punic necropolis of Tuvixeddu, another in the area around the churches of St. Lucifer and San Saturn, and Bonaria hill, and a third along the current Viale Regina Margherita, the burial site of the classiari or detachment of sailors of the fleet of Misenum, which was based at the city port.

In the Roman period, although administered by the prefect of the province, the city maintained institutions of Carthaginian origin, such as the Sufeti, magistrates that were elected annually until the time of the granting of the "municipium" status.

[16] The promontory adjoining the city is evidently that noticed by Ptolemy (Κάραλις πόλις καὶ ἄκρα), but the Caralitanum Promontorium of Pliny can be no other than the headland, now called Capo Carbonara, which forms the eastern boundary of the Gulf of Cagliari and the southeast point of the whole island.

An expedition led by Belisarius defeated the Vandals and Cagliari entered the Byzantine administrative system as the seat of the ἄρχων (archon), the provincial governor, an imperial official in charge of the whole of Sardinia (Σαρδηνία) and subject to the Exarchate of Africa.

After the failed attempt at conquest of Sardinia by the Spanish Muslim Mujāhid al-ʿĀmirī in about 1016, the kingdom was divided into four giudicati, one of which was named Callaris, in reference to its capital, now modern Cagliari.

There were three other independent and autonomous giudicati in Sardinia: the Logudoro (or Torres) in the northwest, the Gallura in the northeast, and in the east the most famous, the long-lived Giudicato of Arborea, with Oristano as its capital.

Pisa and the maritime republic of Genoa had a keen interest in Sardinia because it was a perfect strategic base for controlling the commercial routes between Italy and North Africa.

In 1215 the Pisan Lamberto Visconti, giudice of Gallura, obtained by force from the Torchitorio IV of Cagliari and his wife Benedetta the mountain located east of Santa Igia.

In 1258 after the defeat of William III, the last giudice of Cagliari, the Pisans and their Sardinian allies (Arborea, Gallura and Logudoro) destroyed the old capital of Santa Igia.

The Giudicato of Cagliari was divided into three parts: the northwest third went to Gallura; the centre was incorporated into Arborea; the region of Sulcis and Iglesiente in the south-west was given to the Pisan della Gherardesca family, while the Republic of Pisa maintained the control over its colony of Castel di Castro.

Since 1326, the city, having expelled the Pisans and been repopulated by Catalans, Valencians and Aragonese, began a new period of development, soon interrupted by the war between the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Judicatus of Arborea.

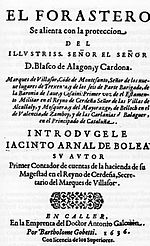

Here were born or lived people of high caliber such as Sigismund Arquer, scholar, theologian, jurist and geographer, who died at the stake in Toledo, charged with being a Lutheran;[19] the lawyers John Dexart,[20] Francis Bellit,[21] Antonio Canales de Vega [22] and Francis Aleo;[23] the physician Joan Thomas Porcell;[24] the historian Giorgio Aleo;[25] the theologian Dimas Serpi;[26] Antonio Maria da Esterzili, author of the first play in Campidanese Sardinian;[27] the writer Roderigo Hunno Baeza, author of "Caralis panegyricus", a poem in Latin, composed around 1516, in which he exalted the city of Cagliari; Jacinto de Arnal Bolea, author of the first novel set in Cagliari, El forastero;[28] Juan Francisco Carmona;[29] the writer and historian Salvatore Vidal;[30] the poets Jose Delitala Y Castelvì and Joseph Zatrillas Vico;[31] the political officer of the Spanish Empire Vincenzo Bacallar Y Sanna; and the Marquis of San Felipe.

But the decadence that the Spanish Empire experienced in the second half of the seventeenth century also damaged the city and exposed it to a serious outbreak of plague in 1656, from which came by municipal vow the Feast of Sant'Efisio, still the most important religious event of the island.

But the eighteenth century was the era of absolute monarchies, and the new ruling house gradually transformed the old kingdom created by the medieval Aragonese kings into one best suited to the needs of the new times.

Nevertheless, the city slowly grew and benefitted from the Age of Enlightenment, with the reorganization of the university, the strengthening of the defense system, the restructuring of the Royal Palace, and access to the markets of central and northern Italy and Europe.

In 1893 a suburban steam tram service was started, connecting the city center with the towns that are now part of the metropolitan area, Monserrato, Selargius, Quartucciu, and Quartu Sant'Elena.

In order to escape the bombardments and the misery of the destroyed town, almost everyone left Cagliari and moved to the countryside or rural villages, often living with friends and relatives in overcrowded houses.

After the Italian armistice with the Allies in September 1943, the German Army took control of Cagliari and the island, but soon retreated peacefully in order to reinforce its positions in mainland Italy.

The city was so quickly rebuilt that there was talk of the Cagliari miracle, and many apartment blocks were erected in new residential districts, often created with poor planning as to recreational areas.

The Constitution of the Italian Republic, born from the ruins of war declared by Mussolini and the Savoy Monarchy, reconstituted the political unity of the island, begun with the Perfect Fusion in 1847, creating the Autonomous Region of Sardinia.

Nowadays Cagliari is the hub of a modern metropolitan area of about half a million inhabitants, with a vibrant and differentiated economy, which makes it the largest and richest community of Sardinia with a standard of living equal to that of the cities of northern Italy and well away from the degradation of those in the south.