History of Cusco

According to the legend collected by the "Inca" Garcilaso de la Vega, Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo migrated from Lake Titicaca on the advice of their father, the god Sun.

During the period of Pachacuti and Túpac Yupanqui, the Cusco domain reached Quito, to the north, and to the Maule River, to the south, culturally integrating the inhabitants of 4500 km of mountain ranges.

The map of ancient Cusco is shaped like a cougar, with the central Haucaypata square (in the place of the Plaza de Armas) in the position that would occupy the animal's chest.

On August 11, 1533, Francisco Pizarro began his trip from Cajamarca to Cusco accompanied by Túpac Huallpa and, although Garcilaso points out that it is another character, the warrior Chalcuchimac.

[9] the Spaniards agreed in Xaquixaguana, near the city of Cuzco, to make Manco Cápac as indigenous sovereign, son of Huayna Capac, 20 years old,[10] from Charcas.

The young prince was eager to collaborate with the expulsion of Cusco from the troops of the Inca general Quizquiz, Atahualpa's trusted man and defender of a rival panaka.

In November of 1533, the troops of Quizquiz, fearing to be sieged, left the city and were persecuted until Anta, where they presented battle, but were defeated, fleeing their leader to Paruro.

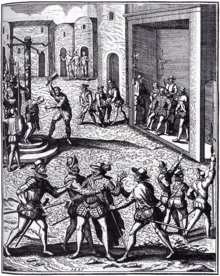

Within the city, 200 conquerors commanded by Hernando, Juan and Gonzalo Pizarro with Nicaraguans and no more than 1,000 Cañaris and Chachas at their service, were reduced to a desperate situation within the framework of the Aucaypata square and which ended with the miracle of Suturhuasi.

In September, preparing a second siege of Cusco, Tiso Yupanqui, main general of Manco Inca, successfully led several clashes against the Spaniards.

According to an anonymous chronicler from 1539, in that battle Tiso Yupanqui captured "several dozen" of Spaniards and "made them slaves", while also adorning the fortress with "200 heads of Christians and 150 horse leathers".

Then he undertook the campaign against Manco Inca, giving him a severe defeat in Vitcos, a mysterious place that some researchers, such as Juan José Vega (1992), suspect Machu Picchu has been.

Diego de Almagro, willing to forcefully defend the territories he considered his own, left Cusco to face the troops led from Lima by Hernando Pizarro, but was defeated in Battle of Las Salinas on April 6, 1538.

The first viceroy, Blasco Núñez Vela (1544-1546), who ruled Peru during the reign of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1516-1556), was the bearer of laws that cut the power and the sistem of the encomenderos and these were not accepted by them.

[18] In Cusco, Gonzalo Pizarro rebelled against the Viceroy, obtaining the support of the Real Audiencia of Lima and the cabildos, for which he exercised power as sovereign of the viceroyalty between 1544 and 1548.

It was the knot of the most important roads, such as the one that arrived in Buenos Aires from Lima, after climbing the Andes through the Huancavelica, Huamanga (Ayacucho), Andahuaylas, Cusco, Puno, La Paz, Potosí, Salta, Tucumán and Córdoba.

Thus, Potosí or Huancavelica were two reciprocal riches and Cusco was a compulsory bridge between the two, although the Huancavelica-Chincha-Pisco-Arica-Potosí route was also used, where the Pisco-Arica section was made by sea navigation and the remaining ones on horse/mule back.

Also in 1560, Viceroy Toledo imposed important changes in the political administration of the rural economy with the reductions of Indigenous, special areas of agricultural activity where native communities produced for their own benefit.

The transportation of goods and the flourishing trade allowed the appearance of wealthy criollo landowners, such as Diego de Esquivel y Jaraba, a native of Cusco, who thanks to his fortune could become Marquis of Valleumbroso in the mid-17th century.

A devastating earthquake in Cusco on March 31, 1650,[27] allowed bold plans to renovate the city, and Spaniard Bishop Manuel de Mollinedo y Angulo was the animator and patron of many important works of art and buildings.

The rise of mining activity in Huancavelica and Potosí generated an important migration of mita mineworkers for the work and the transportation of goods, whose the latters the center of operations was Cusco.

As a result of the Bourbon Reforms and, also because of the Potosí's mita system of mandatory unpaid personal services and abuse of corregidores and judges toward mineworkers, in 1780 the city of Cusco was convulsed by the movement initiated by the cacique José Gabriel Condorcanqui, better known as Túpac Amaru II, that rose against the Spanish administration.

Under this revolution the Real Audiencia of Cusco was established and there was a migration of several noble families of Spaniards to the cities of Lima and Arequipa fearful of indigenous reactions.

On the eve of the independence, the Intendancy of Cuzco, formed in 1784, included the provinces of Cusco, Abancay, Aymaraes, Calca-Lares, Urubamba, Cotabambas, Paruro, Chumbivilcas, Tinta (originally called Canas-Canchis), Quispicanchi and Paucartambo.

The population of the intendancy did not vary much in the independence era, from 216,282 inhabitants in 1796 (according to the census of Viceroy Francisco Gil de Taboada, who ruled the Viceroyalty of Peru during the reign of Charles IV of Spain), to 216,382 in May 1822, on the occasion of the elections to the first Republican Congress.