Inca Empire

Anthropologist Gordon McEwan wrote that the Incas were able to construct "one of the greatest imperial states in human history" without the use of the wheel, draft animals, knowledge of iron or steel, or even a system of writing.

The Inca rulers (who theoretically owned all the means of production) reciprocated by granting access to land and goods and providing food and drink in celebratory feasts for their subjects.

[21] To those earlier civilizations may be owed some of the accomplishments cited for the Inca Empire: "thousands of kilometres/miles of roads and dozens of large administrative centers with elaborate stone construction...terraced mountainsides and filled in valleys", and the production of "vast quantities of goods".

[22] Carl Troll has argued that the development of the Inca state in the central Andes was aided by conditions that allow for the elaboration of the staple food chuño.

It narrates the adventure of a couple, Manco Capac and Mama Ocllo, who were sent by the Sun God and emerged from the depths of Lake Titicaca (pacarina ~ paqarina "sacred place of origin") and marched north.

He then sent messages to their leaders extolling the benefits of joining his empire, offering them presents of luxury goods such as high quality textiles and promising that they would be materially richer as his subjects.

[36] This view is challenged by historian Osvaldo Silva who argues instead that it was the social and political framework of the Mapuche that posed the main difficulty in imposing imperial rule.

[36] Silva does accept that the battle of the Maule was a stalemate, but argues the Incas lacked incentives for conquest they had had when fighting more complex societies such as the Chimú Empire.

[39] It was clear that they had reached a wealthy land with prospects of great treasure, and after another expedition in 1529 Pizarro traveled to Spain and received royal approval to conquer the region and be its viceroy.

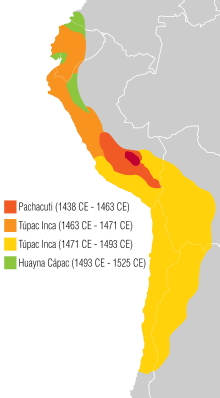

[40] When the conquistadors returned to Peru in 1532, a war of succession between the sons of Sapa Inca Huayna Capac, Huáscar and Atahualpa, and unrest among newly conquered territories weakened the empire.

The first engagement between the Inca and the Spanish was the Battle of Puná, near present-day Guayaquil, Ecuador, on the Pacific Coast; Pizarro then founded the city of Piura in July 1532.

Manco Inca then retreated to the mountains of Vilcabamba and established the small Neo-Inca State, where he and his successors ruled for another 36 years, sometimes raiding the Spanish or inciting revolts against them.

In spite of the fact that the Inca kept excellent census records using their quipus, knowledge of how to read them was lost as almost all fell into disuse and disintegrated over time or were destroyed by the Spaniards.

The exact linguistic topography of the pre-Columbian and early colonial Andes remains incompletely understood, owing to the extinction of several languages and the loss of historical records.

[61] Men on the other hand, "weeded, plowed, participated in combat, helped in the harvest, carried firewood, built houses, herded llama and alpaca, and spun and wove when necessary".

[68] In addition to the mummification process, the Inca would bury their dead in the fetal position inside a vessel intended to mimic the womb for preparation of their new birth.

The ayllus were divided into two parts that could be Hanan or Hurin, Alaasa or Massaa, Uma or Urco, Allauca or Ichoc; according to Franklin Pease, these terms were understood as "high or low," "right or left," "male or female," "inside or outside," "near or far," and "front or back.

[80] In return, the state provided security, food in times of hardship through the supply of emergency resources, agricultural projects (e.g. aqueducts and terraces) to increase productivity, and occasional feasts hosted by Inca officials for their subjects.

[85] They also built agrobiological experimentation centers such as Moray (Cuzco), Castrovirreyna (Huancavelica) and Carania (Yauyos), through circular terraces where the products of the entire empire were reproduced.

During the colonial period, pastures diminished or degraded due to the massive presence of introduced Spanish animals and their feeding habits, significantly altering the Andean environment.

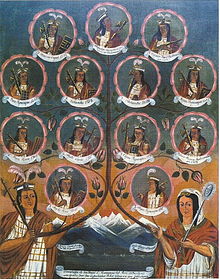

Following Pachacuti, the Sapa Inca claimed descent from Inti, who placed a high value on imperial blood; by the end of the empire, it was common to incestuously wed brother and sister.

Moreover, Cusco was considered cosmologically central, loaded as it was with huacas and radiating ceque lines as the geographic center of the Four-Quarters; Inca Garcilaso de la Vega called it "the navel of the universe".

According to historians Kenneth Mills, William B. Taylor, and Sandra Lauderdale Graham, the collcapata patterns "seem to have expressed concepts of commonality, and, ultimately, unity of all ranks of people, representing a careful kind of foundation upon which the structure of Inkaic universalism was built."

Chronicler Bernabé Cobo wrote: The royal standard or banner was a small square flag, ten or twelve spans around, made of cotton or wool cloth, placed on the end of a long staff, stretched and stiff such that it did not wave in the air and on it each king painted his arms and emblems, for each one chose different ones, though the sign of the Incas was the rainbow and two parallel snakes along the width with the tassel as a crown, which each king used to add for a badge or blazon those preferred, like a lion, an eagle and other figures.

)-Bernabé Cobo, Historia del Nuevo Mundo (1653)Guaman Poma's 1615 book, El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno, shows numerous line drawings of Inca flags.

Key wind instruments included the quena (made of cane and bone), zampoña, pututo or huayla quippa, cuyhui (a five-voice whistle), and pincullo (a long flute).

The Inca army was the most powerful at that time, because any ordinary villager or farmer could be recruited as a soldier as part of the mit'a system of mandatory public service.

[142] Inca weaponry included "hardwood spears launched using throwers, arrows, javelins, slings, the bolas, clubs, and maces with star-shaped heads made of copper or bronze".

The people of the Andes, including the Incas, were able to adapt to high-altitude living through successful acclimatization, which is characterized by increasing oxygen supply to the blood tissues.

For the native living in the Andean highlands, this was achieved through the development of a larger lung capacity, and an increase in red blood cell counts, hemoglobin concentration, and capillary beds.