History of George Town, Penang

Today, the city, well known for its cultural diversity, colonial-era architecture and street food, is a booming tourist destination and still serves as the financial centre of northern Malaysia.

In the 1770s, the British East India Company, seeking to expand its presence into Southeast Asia, instructed Francis Light to form trade relations in the Malay Peninsula.

[1][2][6] Light subsequently wrote to his superiors regarding the offer, arguing that Penang Island could serve as a "convenient magazine for trade", and its strategic location would allow the British to check Dutch and French territorial gains in Southeast Asia.

[1][2][7] When Light reneged on his promise of British military assistance against Siam, in 1791 the Kedah sultan assembled an army and a fleet of pirates in what is now Seberang Perai to recapture the Prince of Wales Island.

[12] Attracted by the promise of free trade without having to pay any form of tax or duties, and assured of their safety at the British-governed harbour, merchants flocked into George Town; consequently, the number of incoming vessels rose exponentially from 85 in 1786 to 3,569 in 1802.

[18] In the early 19th century, Penang, which by then comprised both the Prince of Wales Island and a strip of the Malay Peninsula named Province Wellesley (now Seberang Perai), emerged as a centre of spice production and trade within Southeast Asia.

[33][34] Although its importance became secondary to Singapore's, George Town remained a vital British entrepôt within Southeast Asia, funneling the exports meant for global shipping lines which had bypassed other regional harbours.

[34] These factors were crucial, as it established the Malacca Strait as part of the main sea route between Europe and Asia, with George Town as the first port-of-call east of the Indian subcontinent and a vital link in the international telegraph lines.

Aside from the sizeable Chinese, Malay, Indian, Peranakan, Eurasian and Siamese communities, there were significant minorities of Burmese, British, Javanese, Japanese, Sinhalese, Jewish, German and Armenian origin.

[11] While the Europeans predominated in the various professional fields, and ran mercantile and shipping firms, the Peranakans and the Eurasians tended to enter the nascent civil service as lawyers, engineers, architects and clerks.

The rapid population growth that resulted from the booming economy led to a number of social problems, chiefly the inadequate sanitation and public health facilities, as well as rampant crime.

[40][41] The resulting civil unrest lasted for 10 days, before the turf war was eventually put down by the Straits Settlements authorities under newly appointed Lieutenant-Governor Edward Anson, who were assisted by European residents and reinforcements from Singapore.

[34][39][46] By the end of the 19th century, George Town also evolved into a leading financial centre of British Malaya, as mercantile firms and international banks, including Standard Chartered and HSBC, established regional branches within the city.

With improved access to education and rising living standards, George Town soon enjoyed substantial press freedom and there was a greater degree of participation in municipal affairs by its Asian residents.

Not only did the British Army abandon the Batu Maung Fort without firing a single shot, they also surreptitiously evacuated the city's European residents, leaving ethnic Asians to the mercy of the impending Japanese occupation.

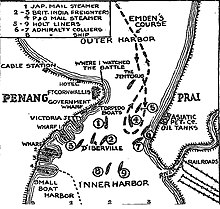

[66][67] Between 1942 and 1944, George Town became the port of call and a replenishment hub for the submarines of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the Kriegsmarine (of Nazi Germany) and the Regia Marina (of the Kingdom of Italy).

Under Operation Jurist, a British Royal Navy fleet, led by HMS Nelson, accepted the surrender of the Japanese garrison in Penang on 2 September 1945.

A British Royal Marines contingent landed at Swettenham Pier on the following day and subsequently dispersed to capture key locations, including the Eastern & Oriental Hotel, Penang Hill and the military facilities in Gelugor.

[53] As with the rest of Penang, George Town was placed under a military administration until 1946, as the British sought to restore order in the face of an emerging communist insurgency.

As the gradual withdrawal of the Western colonial powers in Southeast Asia continued taking shape, the independence of Malaya as a united political entity seemed an inevitable conclusion.

The British government subsequently allayed the fears raised by the secessionists by guaranteeing George Town's free port status and by reintroducing municipal elections for the city in 1951.

"[80]The ceremony was followed by a week-long celebration marking the official elevation of George Town into a city - as well as the centenary of the local government and the New Year's Day - which lasted from 1 to 6 January, and included street festivities and a Chingay procession.

[78][81][83] While the Royal Commission was underway, the George Town City Council was concurrently suspended and its functions were transferred temporarily to the then chief minister of Penang, Wong Pow Nee.

[87] These events marked the death of the George Town's maritime trade and heralded the start of the city's slow, decades-long decline, which was reversed only in recent years.

[24] Kuala Lumpur soon outstripped George Town as Malaysia's largest city and financial centre, while Port Klang rapidly became the country's busiest seaport.

In the 1990s, as George Town's banks began reassessing their spatial requirements to accommodate larger business volumes, a number of commercial developments were launched along the city's Northam Road.

In response, NGOs based within the city, such as the Penang Heritage Trust, began to mobilise public support and form strategic partnerships for the conservation of these historic buildings.

[107][7] In the case of the new commercial properties along Northam Road, cheap unskilled labour from the poorer countries in the region, such as Bangladeshis and Nepalis, filled the void left by the quality subcontractors who had moved to Kuala Lumpur.

[108] Since then, a network of sirens has been installed throughout George Town as part of a national tsunami warning system designed to alert the public of such calamities in the future.

[123] Moreover, George Town, as the economic and financial centre of northern Malaysia, is now home to a vibrant services sector, augmented by its booming tourism, retail and startup industries, while a growing number of expatriates and returning Penangite émigrés have repurposed the city's heritage properties for business enterprises.