History of German settlement in Central and Eastern Europe

There are still substantial numbers of ethnic Germans in the Central European countries that are now Germany and Austria's neighbors to the east—Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, and Hungary.

Finland, the Baltics (Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania), the Balkans (Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia, Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey), Eastern Europe (Moldova, Ukraine, Belarus, Russia), and the Caucasus (Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan) also have smaller but still significant numbers of citizens of German descent.

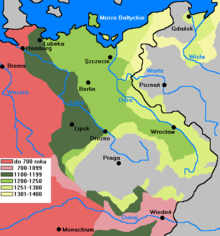

After the Carolingian Empire was divided, these people found themselves in the eastern part, known as East Francia or Regnum Teutonicum, and over time became known as Germans.

Local Slavic leaders in late Medieval Pomerania and Silesia continued inviting German settlers to their territories.

Hanseatic towns and trade stations usually hosted relatively large German populations, with merchant dynasties being the wealthiest and political dominant fractions.

When the Thirty Years' War devastated Central Europe, many areas were completely deserted, others suffered severe population drops.

The concept of nationalism was based on the idea of a people who shared a common bond through race, religion, language and culture.

Most German settled regions of South Central and Southeastern Europe were instead included in the multi-ethnic Habsburg monarchy of Austria-Hungary.

Starting in the late 19th century, an inner-Prussian migration took place from the very rural eastern to the prospering urban western provinces of Prussia (notably to the Ruhr area and Cologne), a phenomenon termed Ostflucht.

[8] Driven by nationalist intentions, the Prussian state established a Settlement Commission as countermeasure, that was to settle more Germans in these regions.

Perceptions of this persecution filtered back into Germany, where reports were exploited and amplified by the Nazi party as part of their drive to national popularity as savior of the German people.

It became the Free City of Danzig, an independent quasi-state under the auspices of the League of Nations governed by its German residents but with its external affairs largely under Polish control.

It issued its own stamps and currency, bearing the legend "Freie Stadt Danzig" and symbols of the city's maritime orientation and history.

From the Polish Corridor, many ethnic Germans were forced to leave throughout the 1920s and 1930s,[citation needed] while Poles settled in the region building the sea port city Gdynia (Gdingen) next to Danzig.

Thereafter, the Nazis under the Bavaria-born Gauleiter Albert Forster achieved dominance in the city government - which, nominally, was still overseen by the League of Nations' High Commissioner.

Germany feigned an interest in diplomacy (delaying the Case White deadline twice), to try to drive a wedge between Britain and Poland.

Many of the propaganda themes of the Nazi regime against Czechoslovakia and Poland claimed that the ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche) in those territories were persecuted.

The status of ethnic Germans, and the lack of contiguity resulted in numerous repatriation pacts whereby the German authorities would organize population transfers (especially the Nazi–Soviet population transfers arranged between Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, and others with Benito Mussolini's Italy) so that both Germany and the other country would increase their "ethnic homogeneity".

Except for Memelland, the Baltic states were assigned to the Soviet Union, and Germany started pulling out the Volksdeutsche population after reaching respective agreements with Estonia and Latvia in October 1939.

After the final Soviet offensives began in January 1945, hundreds of thousands of German refugees, many of whom had fled to Danzig by foot from East Prussia (see evacuation of East Prussia), tried to escape through the city's port in a large-scale evacuation that employed hundreds of German cargo and passenger ships.

[17] As it became evident that the Allies were going to defeat Nazi Germany decisively, the question arose as to how to redraw the borders of Central and Eastern European countries after the war.

The final decision to move Poland's boundary westward was made by the US, Britain and the Soviets at the Yalta Conference, shortly before the end of the war.

The open question was whether the border should follow the eastern or western Neisse rivers, and whether Stettin, the traditional seaport of Berlin, should remain German or be included in Poland.

The northeastern third of East Prussia was directly annexed by the Soviet Union and remains part of Russia to this day.

They agree that any transfers that take place should be effected in an orderly and humane manner.The expulsion of Germans after World War II refers to the expulsion of German colonists and collaborationists from the former eastern territories of Germany, former Sudetenland and other areas across Europe in the first five years after World War II.

[19] As the Red Army advanced towards Germany at the end of World War II, a considerable exodus of German refugees began from the areas near the front lines.

Most of the past research provided a combined estimate of 13.5-16.5 million people, including those that were evacuated by German authorities, fled or were killed during the war.

However, recent research places the number at above 12 million, including all those who fled during the war or migrated later, forcibly or otherwise, to both the Western and Eastern zones of Germany and to Austria.

[20] Recent analyses have led some historians to conclude that the actual number of deaths attributable to the flight and expulsions was in the range of 500,000 to 1.1 million.

According to a survey by the Allensbach Institut in November 2005, 38% of Czechs believe Germans want to regain territory they lost or will demand compensation.