History of Icelandic

The unique development of Icelandic, which eventually resulted in its complete separation from Norwegian and the other Scandinavian languages, began with the landnám or first settlement.

The key position of Denmark as the focal point of the whole area meant that the language was often simply called "Danish" (dǫnsk tunga).

[1] Even though the first hints of individual future developments were already identifiable in different parts of the vast region, there were no problems with mutual intelligibility.

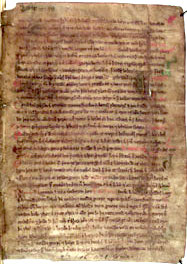

Sometime in the latter half of the 12th century the First Grammatical Treatise (Fyrsta Málfrœðiritgerðin) was composed, a highly original description of the language unique in Europe at the time.

This is particularly true of the ancient epic poetry, which, due to its metric structure and oral tradition, conserved notably archaic forms.

Between 1050 and 1350 Icelandic began to develop independently from other Scandinavian and Germanic languages; it is particularly conservative in its inflectional morphology and notably homogeneous across the country.

From the manuscripts it has not been possible to determine whether dialects ever existed in Iceland; all indications suggest that from the outset the language has maintained an extraordinary level of homogeneity.

Norwegian and Swedish developed more slowly, but show equally notable differences from Icelandic, which is always more conservative and has maintained even to this day many common Scandinavian features.

Icelandic is the only Germanic language to have conserved the word-initial consonant sequences ⟨hl, hr, hn⟩, at least from a graphic point of view (their pronunciation is in part modified by the desonorization of the second consonantal element): Icelandic hljóð, hrafn, hneta, cf English loud, raven, nut, Swedish ljud, ramn (toponymic only), nöt, German Laut, Rabe, Nuss.

In the period from 1350 to 1550, coinciding with the total loss of independence and Danish rule, the difference between Norwegian and Icelandic grew even larger.

Only in western Norway (whence came the original settlers of Iceland) were the dialects kept relatively pure and free from Danish influence, so much so that in the second half of the 19th century the linguist Ivar Aasen created an authentic Norwegian idiom on the basis of them, first called landsmål "national language" and later nynorsk or "neo-Norwegian", which obtained immediate recognition as an official language of the state and is now particularly used in Western Norway.

In the consonant system there have also been notable changes, for example the desonorization of plosives, the rise of a correlative sonorant for nasals and liquids (pre-stopping) and preaspiration.

The modern Icelandic alphabet has developed from a standard established in the 19th century primarily by the Danish linguist Rasmus Rask.

It is ultimately based heavily on an orthographic standard created in the early 12th century in a mysterious document known as The First Grammatical Treatise by an anonymous author who has later been referred to as the 'First Grammarian'.

Later 20th century changes include most notably the adoption of é, which had previously been written as je (reflecting the modern pronunciation), and the abolition of z in 1973.

Even though the vast majority of Icelandic toponyms are native and clearly interpretable (for example Ísa-fjörður "ice fjord", Flat-ey "flat island", Gull-foss "golden waterfall", Vatna-jökull "water glacier", Reykja-vík "bay of smoke", Blanda "the mixed (river)" (which is formed by the confluence of different rivers)) there are some that up to now have resisted any plausible interpretation, even in the light of the Celtic languages.

For example, Esja (a mountain on Kjalarnes), Ferstikla (a farm near Hvalfjörður), Vigur (an island in Ísafjarðardjúp), Ölfus (an area of Árnessýsla, traversed by the river Hvíta-Ölfusá), Tintron (a volcanic crater in Lyngdalsheiði), Kjós (the area that gives its name to Kjósarsýsla), Bóla (a farm in Skagafjörður) and Hekla (a famous Icelandic volcano).

Some scholars, such as Árni Óla, have concerned themselves with the question, attempting to demonstrate this hypothesis, which would force a complete rewrite of Icelandic history.

Naturally, there have been numerous attempts to explain the names in terms of Icelandic: Kjós, for example, could come from the root of the verb kjósa, and therefore mean "the chosen land"; moreover, there is also the common Norwegian surname Kjus.

These influences are very slight and most notable in simple Gaelic names that have been more common in Iceland than elsewhere in Scandinavia over the centuries, Njáll – Niall, Brjánn – Brian, Kaðlín – Caitlín, Patrekur – Padraig, Konall – Conall, Trostan – Triostan, Kormákur – Cormac.

German predigen); more recently the very common náttúra "nature", persóna "person" (originally Etruscan, one of the few remaining words in use of that language) and partur "part".

With regard to modern languages, Icelandic has been influenced (in recent times quite heavily) only by English, particularly in the technical lexis and by the younger generation.

In languages such as Italian, English words are simply borrowed just as they are; in contrast, in Icelandic they are adapted to the local phonetic and morphological system.