History of Istria

[4] Romans established the port of Pietas Iulia (modern Pula)[5] and gradually converting the inland areas into latifundia, large estates worked by colonists and locals.

Although pockets of Illyrian resistance remained in the hilly interior, they succumbed in time to the Romans’ combination of military and economic superiority.

Under Emperor Augustus, Istria was incorporated into the region of Venetia et Histria, as part of the Roman mainland of Italia.

[8] The period between the 2nd and 5th century AD saw the incursions of Germanic tribes, a sustained influx of refugees from Pannonia and other provinces, political instability amid infighting for the Roman throne, and decline of the economy.

[8] In 538/539, Istria was incorporated into the Byzantine Empire, and consequently placed under administrative and military jurisdiction of the Exarchate of Ravenna.

[12] At the beginning of the 7th century, Istrian eastern and inland regions were invaded by Slavs, while the coastal area resisted these attacks.

[19] The mission of an abbot Martin sent by Pope John IV to "travel the length of Dalmatia and Istria with large sums of money for the redemption of captives held by pagans" in 640–642, indicates that by that time the Slavs had settled in the region.

The basilica of Vrsar was probably burned during one of the Avaro-Slavic invasions, and it has been suggested that also the church of St Fusca (Sveta Foška) near Žminj (Gimino) suffered the same fate by the same hands.

[29] The seeds of Istria's dissolution were sown under increasingly weak Frankish rule, which enabled most settlements to achieve de facto autonomy.

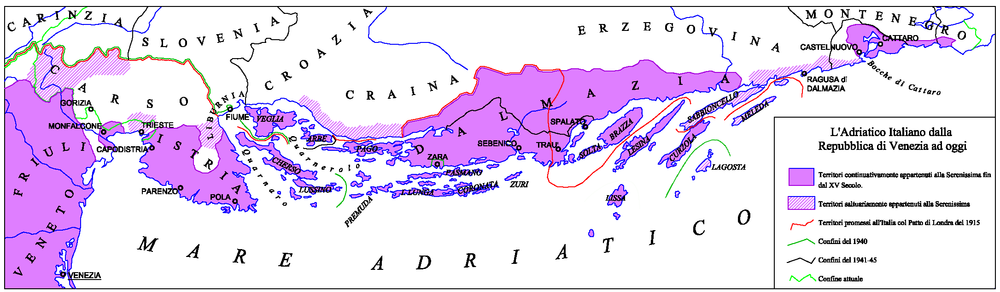

Under Pietro II Candiano, who was Doge of Venice between 932 and 939, Istrian cities signed an act of devotion to the Venetian rule.

[30] The fleet visited all the main Istrian and Dalmatian cities, whose citizens, exhausted by the wars between the Croatian king Svetislav and his brother Cresimir, swore an oath of fidelity to Venice.

[31] During the 13th century, the Patriarchate's rule weakened and the towns kept surrendering to Venice – Poreč in 1267, Umag in 1269, Novigrad in 1270, Sveti Lovreč in 1271, Motovun in 1278, Kopar in 1279, and Piran and Rovinj in 1283.

[31] The wealthier coastal towns cultivated increasingly strong economic relationships with Venice and by 1348 were eventually incorporated into its territory, while their inland counterparts fell under the sway of the weaker Patriarchate of Aquileia, which became part of the Habsburg Empire in 1374.

A copy of the map inscribed in stone can now be seen in the Pietro Coppo Park in the center of the town of Izola in southwestern Slovenia.

The introduction of limited democracy in 1861, by means of a regional parliament (Diet of Istria) that convened at Parenzo (Poreč), only served to its purpose to the Austrians in defusing Italian calls for the region's union with the newly established Kingdom of Italy, as suffrage was limited to property owners, who were primarily Italian.

[36] However, after the Third Italian War of Independence (1866), when the Veneto and Friuli regions were ceded by the Austrians to the newly formed Kingdom Italy, Istria remained part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, together with other Italian-speaking areas on the eastern Adriatic.

[38] During the meeting of the Council of Ministers of 12 November 1866, Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria outlined a wide-ranging project aimed at the Germanization or Slavization of the areas of the empire with an Italian presence:[39] His Majesty expressed the precise order that action be taken decisively against the influence of the Italian elements still present in some regions of the Crown and, appropriately occupying the posts of public, judicial, masters employees as well as with the influence of the press, work in South Tyrol, Dalmatia and Littoral for the Germanization and Slavization of these territories according to the circumstances, with energy and without any regard.

A secret agreement was made in London in April 1915, according to which Italy was promised South Tyrol, a part of Dalmatia and Istria with Trieste and Gorizia.

At the end of the First World War, Austria-Hungary was defeated in the battle of Vittorio Veneto and asked for an armistice, signed in Padova, on 3 November 1918.

At the peace conference in Paris, Italy was among the winning powers, and obtained the suzerainty over Istria, according to the terms of the Treaty of Rapallo.

After the advent of Fascism in 1922, the portions of the Istrian population that were Croatian and Slovene were exposed to a policy of forced Italianization and cultural suppression.

The organization TIGR, regarded as the first armed antifascist resistance group in Europe, was founded in 1927 and soon penetrated into Slovene and Croatian-speaking parts of Istria.

After the capitulation of Italy in the Second World War, The Yugoslav Partisans officially occupied the region, expelled the fascist authorities, and established the rule of the National Liberation Movement in Croatia which sought to incorporate Istra into the Croatian state.

This lingered and triggered the Istrian-Dalmatian exodus which significantly reduced the Italian population in Istria, particularly in urban areas.