History of Shetland

Due to building in stone on virtually treeless islands—a practice dating to at least the early Neolithic Period—Shetland is extremely rich in physical remains of the prehistoric era, and there are over 5,000 archaeological sites.

[2] A midden site at West Voe on the south coast of Mainland, dated to 4320–4030 BCE, has provided the first evidence of Mesolithic human activity in Shetland.

The Romans were aware of (and probably circumnavigated, seeing in the distance Thule according to Tacitus) the Orkney & Shetland Islands, which they called "Orcades", where they discovered the brochs.

But, according to scholars like Montesanti, "Orkney and Shetland might have been one of those areas that suggest direct administration by Imperial Roman procurators, at least for a very short span of time".

[9] By the end of the 9th century the Scandinavians shifted their attention from plundering to invasion, mainly due to the overpopulation of Scandinavia in comparison to resources and arable land available there.

From the Northern Isles they continued to raid Scotland and Norway, prompting Harald to raise a large fleet which he sailed to the islands.

Ragnvald, Earl of Møre received Orkney and Shetland as an earldom from the king as reparation for his son's being killed in battle in Scotland.

Shetland was Christianised in the late tenth and eleventh centuries due to pressure from the Norwegian kings, especially Olaf Tryggvason.

When Alexander III of Scotland turned twenty-one in 1262 and became of age, he declared his intention of continuing the aggressive policy his father had begun towards the western and northern isles.

The fleet met up in Breideyarsund in Shetland (probably today's Bressay Sound) before the king and his men sailed for Scotland and made landfall on Arran.

One of the main reasons behind the Norwegian desire for peace with Scotland was that trade with England was suffering from the constant state of war.

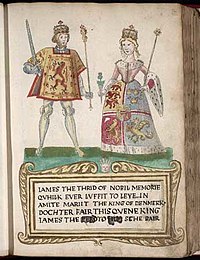

King Christian I of Denmark and Norway was in financial trouble and, when his daughter Margaret became engaged to James III of Scotland in 1468, he needed money to pay her dowry.

[12] Apparently without the knowledge of the Norwegian Riksråd (Council of the Realm) he entered into a commercial contract on 8 September 1468 with the King of Scots in which he pawned his personal interests in Orkney for 50,000 Rhenish guilders.

There was an obligation to retain the language and laws of Norway, which was not only implicit in the pawning document, but is acknowledged in later correspondence between James III and King Christian's son John (Hans).

[16] In 1470 William Sinclair, 1st Earl of Caithness ceded his title to James III and on 20 February 1472, the Northern Isles were directly annexed to the Crown of Scotland.

[17] James and his successors fended off all attempts by the Danes to redeem them (by formal letter or by special embassies were made in 1549, 1550, 1558, 1560, 1585, 1589, 1640, 1660 and other intermediate years) not by contesting the validity of the claim, but by simply avoiding the issue.

The latter commenced the building of Scalloway Castle, but after his execution in 1609 the Crown annexed Orkney and Shetland again until 1643 when Charles I granted them to William Douglas, 7th Earl of Morton.

However, some local merchant-lairds took up where the German merchants had left off, and fitted out their own ships to export fish from Shetland to the Continent.

Laws were changed, weights and measures altered and the language suppressed, a process historians now call "feudalisation" as a means by which Shetland became incorporated into Scotland, particularly during the 17th century.

[25] The Crown might have thought that by prescription (the passage of time) it gave them ownership necessary to give out feudal charters, grants, or licences.

Because the overall treaty was too important to Charles II he eventually conceded that the original marriage document still stood, that his and previous monarchs' actions in granting out the islands under feudal charters were illegal.

Charles II also provided that, in the event of a "general dissolution of his majesty's properties" by which he clearly meant the Act of Union, Shetland was not to be included.

[26] Following a legal dispute with William, Earl of Morton, who held the estates of Orkney and Shetland, Charles II ratified the pawning document by a Scottish Act of Parliament on 27 December 1669 which officially made the islands a Crown dependency and exempt from any "dissolution of His Majesty’s lands".

They have almost identical proportions of Scandinavian matrilineal and patrilineal ancestry (ca 44%), suggesting that the islands were settled by both men and women, as seems to have been the case in Orkney and the northern and western coastline of Scotland, but areas of the British Isles further away from Scandinavia show signs of being colonised primarily by males who found local wives.

Smallpox afflicted the islands in the 17th and 18th centuries, but as inoculations pioneered by those such as Johnnie Notions came into widespread use the population was able to grow more quickly.

By 100 years later the islands' population had been more than halved, mainly due to many Shetland men being lost at sea during the two world wars, and the waves of emigration in the 1920s and 1930s.

The image is from the Icelandic manuscript Flateyjarbók from the 15th century.