History of Warsaw

In that time, the city evolved from a cluster of villages to the capital of a major European power, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth—and, under the patronage of its kings, a center of enlightenment and otherwise unknown tolerance.

In recent years the history-laden city has grown to become the multicultural capital of a modern European state and a major commercial and cultural centre of Central Europe.

Then, a new similar settlement was established on the site of a small fishing village called Warszowa, c. 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) north of Jazdów—by the same Prince Bolesław II.

[3] This struggle resulted in the so-called third order being added to the city's authorities, sharing power with the two bodies controlled by the patrician class: the council and the assessors.

Following an election, the king-elect was obliged to sign the pacta conventa (Latin: "agreed accords"), laundry lists of campaign promises, seldom fulfilled, with his noble electors.

The royal architect, Santa Gucci, started to rebuild the Warsovian Castle in the Baroque style, so the King only lived there temporarily, but in 1611 he moved there for good.

The decentralized Polish Crown lacked sufficient power to assert itself in the Great Northern War, which led to Poland to becoming a battlefield between the two neighbouring kingdoms.

Under the Swedish influence, in June 1704 the Polish gentry dethroned Augustus II and at Wielka Wola elected a new king, the pro-Swedish Poznań Voivod Stanisław Leszczyński.

[11] Shortly afterwards, the tides of war changed and on September 1, 1704, Warsaw was retaken by the Saxon army of Augustus II after five days of a severe artillery bombardment.

Following the repeated violations of the Polish constitution by the Russians (especially after the Alexander I's death, when the reactionary Nicholas I assumed power), the 1830 November Uprising broke out.

It started with the assault on Belvedere – the residence of Grand Duke Constantine Pavlovich, the commander-in-chief of Polish army and de facto viceroy of the Congress Poland, as well as at the Arsenal.

The 1830 uprising led to the Polish-Russian war (1831), the greatest battle of which took place on 25 February 1831 in Grochów — a village in the modern northern part of the district, Praga Południe.

[29] The Russian army, during its Great Retreat from Poland, demolished all the Warsovian bridges—and the Poniatowski Bridge that had opened 18 months earlier—and took the equipment from the factories, which made the situation in Warsaw much more difficult.

The German authorities, headed by General Hans von Beseler, needed Polish support in the war against Russia, so they tried to appear friendly to the Poles.

The Russian authorities hadn't allowed the extension the Warsaw's area, because it was forbidden to cross the double line of forts surrounding the city.

For this reason, at the beginning of World War I on the area of today's Śródmieście and the old part of Praga (c. 33 square kilometres (13 sq mi) 750,000 people lived.

According to Lord d’Abernon: The history of contemporary civilization knows no event of greater importance than the Battle of Warsaw, 1920, and none of which the significance is less appreciated.

On 16 December 1922, in the gallery Zachęta, Eligiusz Niewiadomski, a painter with mental disorder, who belonged to the right-wing National Democracy, assassinated the first President of Poland, Gabriel Narutowicz, who had been elected five days earlier by Sejm.

The most important representatives of civil and military administration (along with the Army's Commander-in-Chief, Marshall Edward Rydz-Śmigły) escaped to the Kingdom of Romania, taking with themselves much of the equipment and ammunition intended for the defense of the city.

On 9 September, the German Army tank divisions attacked Warsaw from south-west, but the defenders (with a lot of civil volunteers) managed to stop them in the Ochota district.

[34] On 20 June 1939 while Adolf Hitler was visiting an architectural bureau in Würzburg am Main, his attention was captured by a project of a future German town, Neue deutsche Stadt Warschau.

[37][38] The commander of Verbrennungs und Vernichtungskommando ("Burning and Destruction Detachments"), Jürgen Stroop, destroyed the Ghetto so completely that even house walls did not remain.

Hitler, ignoring the agreed terms of the capitulation, ordered the entire city razed to the ground and the library and museum collections taken to Germany or burned.

Next to the remnants of Gothic architecture the ruins of splendid edifices from the time of Congress Poland and ferroconcrete relics of prewar building jutted out of the rubble.

[3] On 17 January 1945, the Soviet troops entered the left[clarification needed] part of Warsaw and on 1 February 1945 proclaimed the Polish People's Republic (de facto proclamation had taken place in Lublin, on 22 July 1944).

The architects who worked for the Bureau, following the ideas of functionalism and supported by the Soviet puppet Communist regime, decided to renew Warsaw in modern style, with large free areas.

The leader (First Secretary) of the Polish United Workers' Party, (PZPR), Bolesław Bierut, suddenly died in Moscow during the 20th Congress of CPSU in March, probably from a heart attack.

The route and bridge that connect the Warszawa Zachodnia Station area and the Grochów estate—the broad street on the right bank (Praga)—has been named Aleja Stanów Zjednoczonych (The United States Avenue).

In the crisis of the 1980s and hard time of martial law, John Paul II's visits to his native country in 1979 and 1983 brought support to the budding Solidarity movement and encouraged the growing anti-communist fervor there.

[44] In 1979, less than a year after becoming pope, John Paul celebrated Mass in Victory Square in Warsaw and ended his sermon with a call to "renew the face" of Poland: Let Thy Spirit descend!

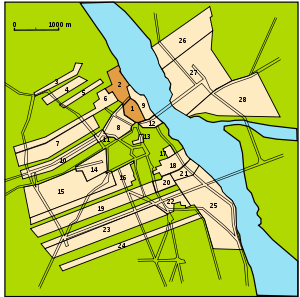

- Old Town

- New Town

- Szymanowska

- Wielądka

- Parysowska

- Świętojerska

- Nowolipie

- Kapitulna

- Dziekania

- Leszno

- Tłumackie

- Mariensztadt

- Dziekanka

- Wielopole

- Grzybów

- Bielino (also [24])

- Stanisławów

- Aleksandria

- Nowoświecka

- Ordynacka

- Tamka-Kałęczyn

- Bożydar-Kałęczyn

- Nowogrodzka

- Bielino (also [16])

- Solec

- Golędzinów

- Praga

- Skaryszew-Kamion