History of democracy

Nevertheless, the critical historical juncture catalyzed by the resurrection of democratic ideals and institutions fundamentally transformed the ensuing centuries and has dominated the international landscape since the dismantling of the final vestige of the British Empire following the end of the Second World War.

[4] Anthropologists have identified forms of proto-democracy that date back to small bands of hunter-gatherers that predate the establishment of agrarian, sedentary societies and still exist virtually unchanged[disputed – discuss] in isolated indigenous groups today.

In these groups of generally 50–100 individuals, often tied closely by familial bonds, decisions are reached by consensus or majority and many times without the designation of any specific chief.

Although fifth-century BCE Athens is widely considered to have been the first state to develop a sophisticated system of rule that we today call democracy,[8][9][10][11][12][13] in recent decades scholars have explored the possibility that advancements toward democratic government occurred independently in the Near East, the Indian subcontinent, and elsewhere before this.

It contains a chapter on how to deal with the sangas, which includes injunctions on manipulating the noble leaders, yet it does not mention how to influence the mass of the citizens—a surprising omission if democratic bodies, not the aristocratic families, actively controlled the republican governments.

The absence of any concrete notion of citizen equality across these caste system boundaries leads many scholars to claim that the true nature of gaṇas and saṅghas is not comparable to truly democratic institutions.

As Aristotle noted, ephors were the most important key institution of the state, but because often they were appointed from the whole social body it resulted in very poor men holding office, with the ensuing possibility that they could easily be bribed.

The constitutional reforms implemented by Lycurgus in Sparta introduced a hoplite state that showed, in turn, how inherited governments can be changed and lead to military victory.

[45] After a period of unrest between the rich and poor, Athenians of all classes turned to Solon to act as a mediator between rival factions, and reached a generally satisfactory solution to their problems.

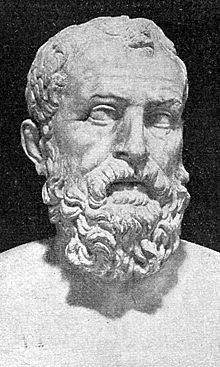

[46][47] Solon (c. 638 – c. 558 BCE), an Athenian (Greek) of noble descent but moderate means, was a lyric poet and later a lawmaker; Plutarch ranked him as one of the Seven Sages of the ancient world.

The retired archons became members of the Areopagus (Council of the Hill of Ares), which like the Gerousia in Sparta, was able to check improper actions of the newly powerful Ecclesia.

[50][51] Even though the Solonian reorganization of the constitution improved the economic position of the Athenian lower classes, it did not eliminate the bitter aristocratic contentions for control of the archonship, the chief executive post.

[citation needed] In the following passage, Thucydides recorded Pericles, in the funeral oration, describing the Athenian system of rule: Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy.

If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if no social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition.

Debate was open to all present and decisions in all matters of policy were taken by majority vote in the Ecclesia (compare direct democracy), in which all male citizens could participate (in some cases with a quorum of 6000).

Because of their influential works, after the rediscovery of classics during the Renaissance, Sparta's political stability was praised,[68][69][10] while the Periclean democracy was described as a system of rule where either the less well-born, the mob (as a collective tyrant), or the poorer classes held power.

[9] Only centuries afterwards, after the publication of A History of Greece by George Grote from 1846 onwards, did modern political thinkers start to view the Athenian democracy of Pericles positively.

This commission, under the supervision of a resolute reactionary, Appius Claudius, transformed the old customary law of Rome into Twelve Tables and submitted them to the Assembly (which passed them with some changes) and they were displayed in the Forum for all who would and could read.

[79] The people of Rome through the assemblies had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of new laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation (or dissolution) of alliances.

[80][81] Roman stability, in Polybius' assessment, was owing to the checks each element put on the superiority of any other: a consul at war, for example, required the cooperation of the Senate and the people if he hoped to secure victory and glory, and could not be indifferent to their wishes.

The background of social unease and the inability of the traditional republican constitutions to adapt to the needs of the growing empire led to the rise of a series of over-mighty generals, championing the cause of either the rich or the poor, in the last century BCE.

Octavian left the majority of Republican institutions intact, though he influenced everything using personal authority and ultimately controlled the final decisions, having the military might to back up his rule if necessary.

[96] Elizabeth Tooker, a professor of anthropology at Temple University and an authority on the culture and history of the Northern Iroquois, has reviewed Weatherford's claims and concluded they are myth rather than fact.

World War II also planted seeds of democracy outside Europe and Japan, as it weakened, with the exception of the USSR and the United States, all the old colonial powers while strengthening anticolonial sentiment worldwide.

Much of Eastern Europe, Latin America, East and Southeast Asia, and several Arab, central Asian and African states, and the not-yet-state that is the Palestinian Authority moved towards greater liberal democracy in the 1990s and 2000s.

[125] The numbers are indicative of the expansion of democracy during the twentieth century, the specifics though may be open to debate (for example, New Zealand enacted universal suffrage in 1893, but this is discounted due to lack of complete sovereignty of the Māori vote).

In Asia, Myanmar (also known as Burma) the ruling military junta in 2011 made changes to allow certain voting-rights and released a prominent figure in the National League for Democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi, from house arrest.

However, conditions partially changed with the election of Suu Kyi's National League for Democracy party and her appointment as the de facto leader of Burma (Myanmar) with the title "state councilor", as she is still not allowed to become president and therefore leads through a figurehead, Htin Kyaw.

In Poland and Hungary, so-called "illiberal democracies" have taken hold, with the ruling parties in both countries considered by the EU and by civil society to be working to undermine democratic governance.

[130] As of November 2024, Almost every incumbent party worldwide facing election in 2024 lost vote share, including in South Africa, India, France, the United Kingdom, and Japan.