History of diabetes

Then, while Paulescu served in army, during World War I, the discovery and purification of insulin for clinical use in 1921–1922 was achieved by a group of researchers in Toronto—Frederick Banting, John Macleod, Charles Best, and James Collip—paved the way for treatment.

The discovery of an antidiuretic substance extracted from the pituitary gland by researchers in Italy (A. Farini and B. Ceccaroni) and Germany (R. Von den Velden) in 1913 paved the way for treatment.

[5][6] The following mixture was prescribed for treatment: "A measuring glass filled with Water from the Bird pond, Elderberry, Fibres of the asit plant, Fresh Milk, Beer-Swill, Flower of the Cucumber, and Green Dates".

They constitute the earliest known references to the presence of sugar in the urine (glycosuria) and to dietary remedies, at least a thousand years before modern European descriptions began to more comprehensively conceptualize the disease.

[9][22][26][27] In-depth probes of Greek etymology agree that the term came from Demetrius of Apamea,[22][27] C. L. Gemmill (1972) states:[22]Caelius Aurelianus prepared a Latin version of the works of Soranus.

98–117 AD), a physician famous for his work on the variations of the pulse, described the symptoms of diabetes as "incessant thirst" and immediate urination after drinking, which he called "urinary diarrhea".

[32] During the Islamic Golden Age under the Abbasid Caliphate,[d] prominent Muslim physicians preserved, systematized and developed ancient medical knowledge from across the Eurasian continent.

[36] The presence of sugar in the urine (glycosuria) and in the blood (hyperglycemia) was demonstrated through the work of a number of physicians in the late 18th century, including Robert Wyatt (1774) and Matthew Dobson (1776).

I judge therefore, that the presence of such a saccharine matter may be considered as the principal circumstance in idiopathic diabetes.In 1788, Thomas Cawley published a case study in the London Medical Journal based on an autopsy of a diabetic patient.

In 1794, Johann Peter Frank of the University of Pavia found that his patients were characterized by "long continued abnormally increased secretion of non-saccharine urine which is not caused by a diseased condition of the kidneys".

This general use of the term, however, has caused a great deal of confusion; as a variety of diseases differing altogether in their nature, except in the accidental circumstances of being accompanied by diuresis, or a large flow of urine, have in consequence been confounded with one another.

John MacLeod, among the Toronto group that later isolated and purified insulin for clinical use, cited this finding as the most convincing proof of an internal secretion in his 1913 book, Diabetes: Its Pathological Physiology.

[54][55][56] In 1909, Belgian physician Jean de Mayer hypothesized that the islets secrete a substance that plays this metabolic role, and termed it insulin, from the Latin insula ('island').

[57] The endocrine role of the pancreas in metabolism, and indeed the existence of insulin, was further clarified between 1921 and 1922 when a group of researchers in Toronto, including Frederick Banting, Charles Best, John MacLeod, and James Collip, were able to isolate and purify the extract.

[64][68] In 1794, Johann Peter Frank gave a relatively clear description of diabetes insipidus, as a "long continued abnormally increased secretion of non-saccharine urine which is not caused by a diseased condition of the kidneys".

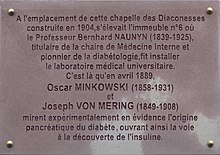

"[70] In 1912, Alfred Eric Frank, then working on diabetes mellitus in the department of Oskar Minkowski in Breslau, reported a specific link to the pituitary gland upon observing a case of a man who had survived after shooting himself in the temple.

[73][74] A general agreement was reached that some of the results that reported diuresis was due to increased pressure and blood flow to the kidney, while the posterior pituitary extract had an antidiurectic effect.

In 1920, Jean Camus and Gustave Roussy summarized a number of years of research, reporting that they had produced polyuria in dogs by puncturing the hypothalamus while leaving the pituitary intact.

In 1947, the anti-diuretic hormone (ADH)-insensitive variety was termed nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI), and attributed to a defect in the loop of Henle and the distal convoluted tubule.

Dietary restriction was first reported successful by John Rollo in 1797, and later by Apollinaire Bouchardat, who observed the disappearance of glycosuria in his patients during the rationing while Paris was besieged by the Germans in 1870.

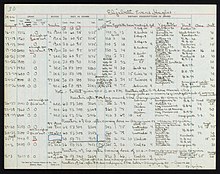

[98] Romanian scientist Nicolae Paulescu, another notable figure in the search for the anti-diabetic factor, began experimenting in 1916 using a slightly saline pancreatic solution like Kleiner's.

[99][100][101][102][103] His extracts resulted in clear reduction of blood and urinary sugar in the tested dogs, but had no immediate effect in his human patients (through rectal injection) that could not be duplicated by doses of saline alone.

[111] As the group prepared for clinical trials, biochemist James Collip joined the team at Banting's request to help purify the extract for human injection.

[132] Once limits were reached, Toronto contracted with Eli Lilly and Company beginning May 1922 with some caution regarding the commercial nature of the firm (see: Insulin#History of study#Patent).

[133][134][135] The 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology awarded to Frederick Banting and John Macleod—publicly shared with Charles Best and James Collip, respectively—sparked controversy as to who was due credit "for the discovery of insulin".

[140] However, the criteria advanced to prioritize the pair's early work alone (before the extract was purified) would itself run into challenges in the 1960s and 1970s as attention was drawn to successes in the same year (Nicolae Paulescu) or earlier (George Ludwig Zuelzer, Israel Kleiner).

[136] As tends to be true of any scientific line of inquiry, "the discovery of a preparation of insulin that could be used in treatment"[141] was made possible through the joint effort of team members, and built on the insight of researchers who came before them.

In 1954, American doctor Joseph H. Pratt, whose lifelong interest in diabetes and the pancreas went back well before the Toronto discovery, published a "reappraisal" of Macleod and Collip's contributions in refining Banting and Best's flawed experiments and crude extract.

However, by 1996, the advent of insulin analogues which had vastly improved absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) characteristics which were clinically meaningful based on this early biotechnology development.

[151] In 1913, researchers in Italy (A. Farini and B. Ceccaroni) and Germany (R. Von den Velden) reported the anti-diuretic effect of the substance extracted from the posterior lobe of the pituitary gland.